Differential Diagnosis of Anterior Knee Pain James J. Lehman, DC, FACO

69 Slides3.17 MB

Differential Diagnosis of Anterior Knee Pain James J. Lehman, DC, FACO Associate Professor of Clinical Sciences Director, Community Health Clinical Education Program University of Bridgeport

Dr. James J. Lehman PowerPoint presentations: Bridgeport.edu/nmsm Cell: 505-238-9501 Email: [email protected]

Learning Objectives Identify injured and painful tissues through careful assessment and intelligent use of neuromusculoskeletal testing and document the findings. Rule-in and rule-out neuromusculoskeletal condition that might present as anterior knee pain. Implement the scientific method and integrate the use of an evaluation protocol practiced by evidence-based and patient-centered chiropractic physicians.

Knee Pain Incidence Knee pain accounts for approximately one third of musculoskeletal problems seen in primary care settings. Rosenblatt RA, Cherkin DC, Schneeweiss R, Hart LG. The content of ambulatory medical care in the United States. An interspecialty comparison. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:892– 7.

Knee Pain Incidence This complaint is most prevalent in physically active patients, with as many as 54 percent of athletes having some degree of knee pain each year. Rosenblatt RA, Cherkin DC, Schneeweiss R, Hart LG. The content of ambulatory medical care in the United States. An interspecialty comparison. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:892–7.

Description of Knee Pain The patient's description of knee pain is helpful in focusing the differential diagnosis. Bergfeld J, Ireland ML, Wojtys EM, Glaser V. Pinpointing the cause of acute knee pain. Patient Care. 1997;31(18):100–7.

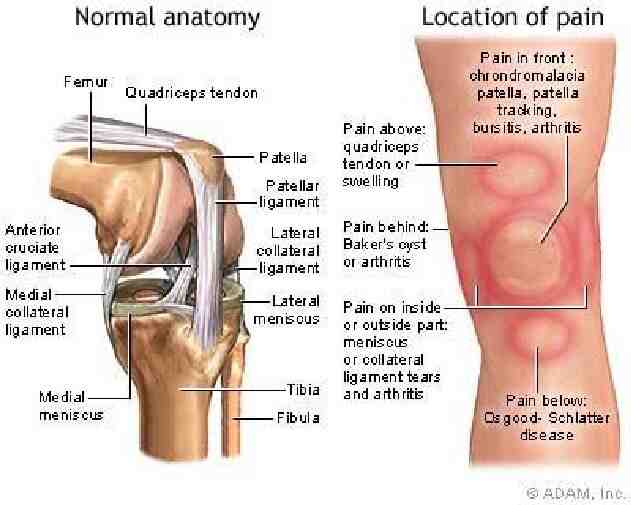

Pain Characteristics It is important to clarify the characteristics of the pain, including its onset (rapid or insidious), location (anterior, medial, lateral, or posterior knee), duration, severity, and quality (e.g., dull, sharp, achy).

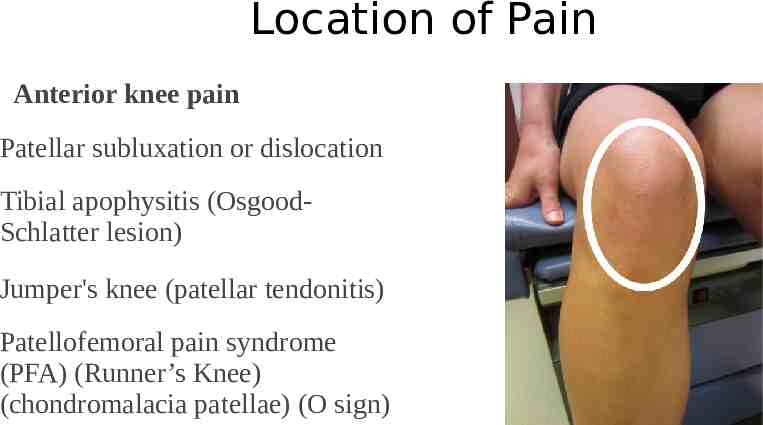

Location of Pain Have the patient point to the painful site. Fortin JD & Falco FJ. The Fortin finger test: An indicator of sacroiliac pain. August 1997. American journal of orthopedics (Belle Mead, N.J.) 26(7):477-80

Detailed History Location Mechanism of injury New or old condition Palliative or Provocative Quality of Pain Radiation or Referred Severity Timing or Treatment

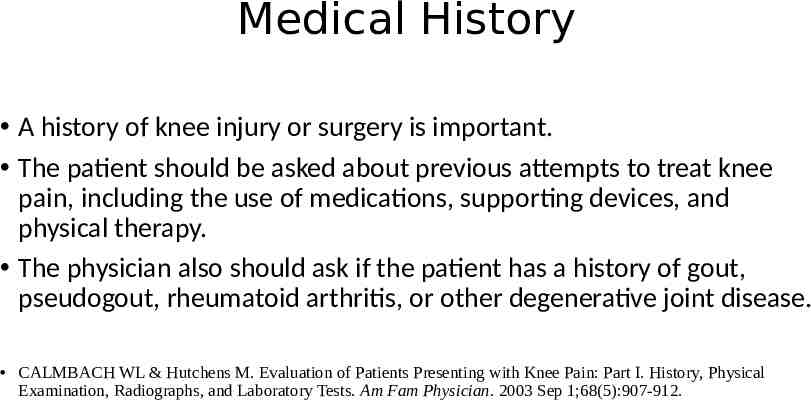

Medical History A history of knee injury or surgery is important. The patient should be asked about previous attempts to treat knee pain, including the use of medications, supporting devices, and physical therapy. The physician also should ask if the patient has a history of gout, pseudogout, rheumatoid arthritis, or other degenerative joint disease. CALMBACH WL & Hutchens M. Evaluation of Patients Presenting with Knee Pain: Part I. History, Physical Examination, Radiographs, and Laboratory Tests. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Sep 1;68(5):907-912.

Diagnosis is the Key to Successful Treatment Knee anatomy Common pain patterns in knee injuries Features of frequently encountered causes of knee pain Specific physical examination skills

Differential Diagnosis The differential diagnosis of knee pain is extensive but can be narrowed with a detailed history, a focused physical examination and, when indicated, the selective use of appropriate imaging and laboratory studies. Calmbach WL & Hutchens M. Evaluation of Patients Presenting with Knee Pain: Part I. History, Physical Examination, Radiographs, and Laboratory Tests. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Sep 1;68 (5):907-912.

Location of Pain Anterior knee pain Patellar subluxation or dislocation Tibial apophysitis (OsgoodSchlatter lesion) Jumper's knee (patellar tendonitis) Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFA) (Runner’s Knee) (chondromalacia patellae) (O sign)

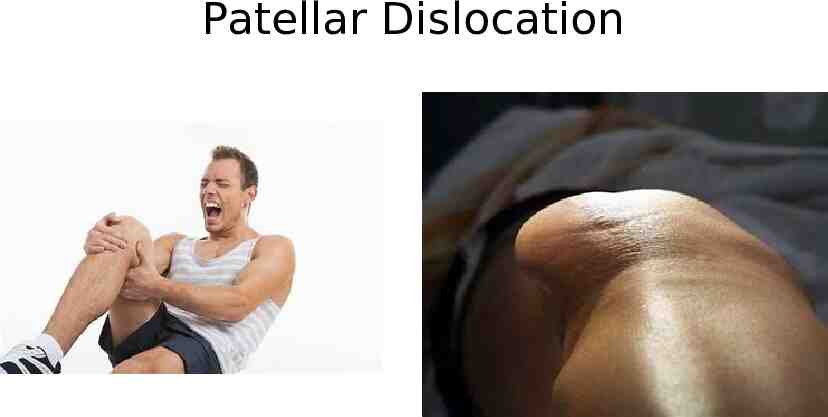

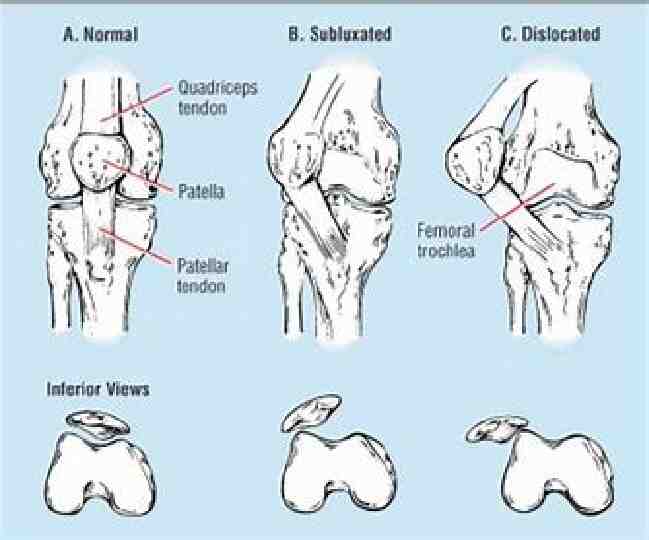

Patellar Dislocation

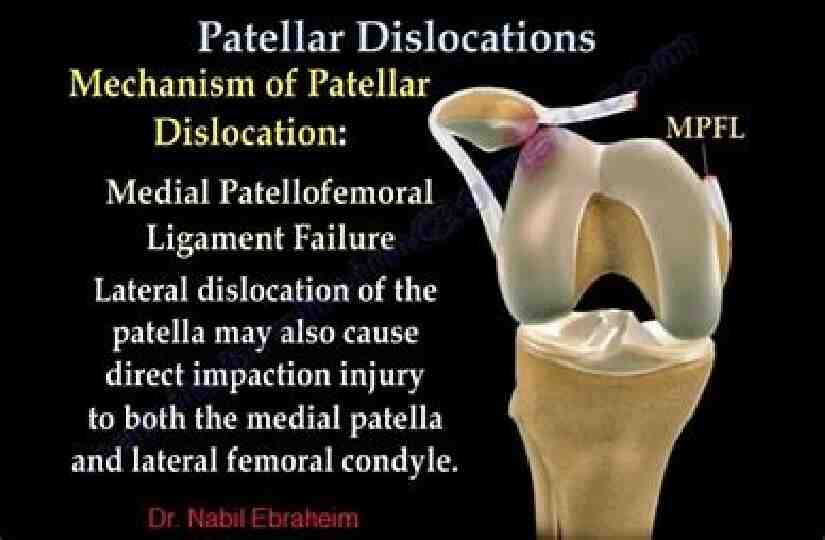

Patellar Subluxation Patellar subluxation is the most likely diagnosis in a teenage girl who presents with giving-way episodes of the knee. Walsh WM. Knee injuries. In: Mellion MB, Walsh WM, Shelton GL, eds. The team physician's handbook. 2d ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 1990:554–78.

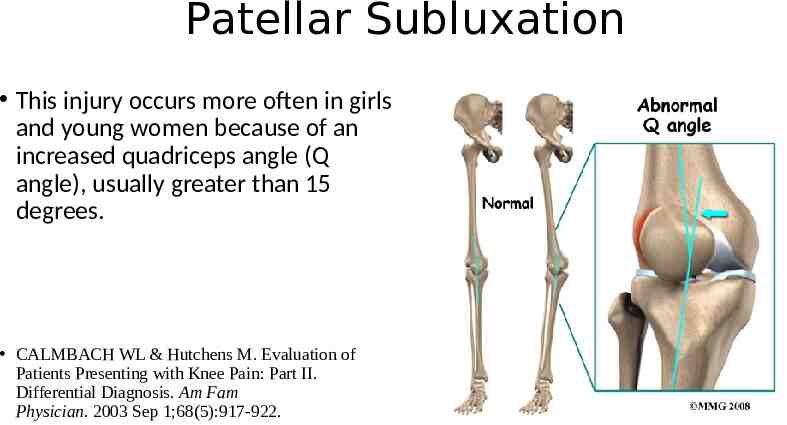

Patellar Subluxation This injury occurs more often in girls and young women because of an increased quadriceps angle (Q angle), usually greater than 15 degrees. CALMBACH WL & Hutchens M. Evaluation of Patients Presenting with Knee Pain: Part II. Differential Diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Sep 1;68(5):917-922.

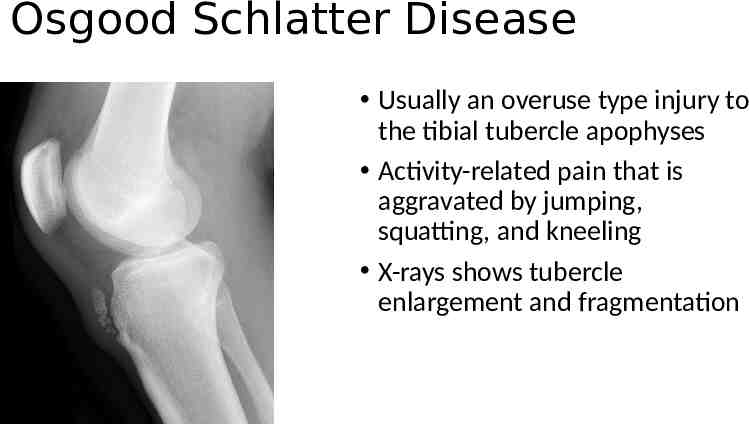

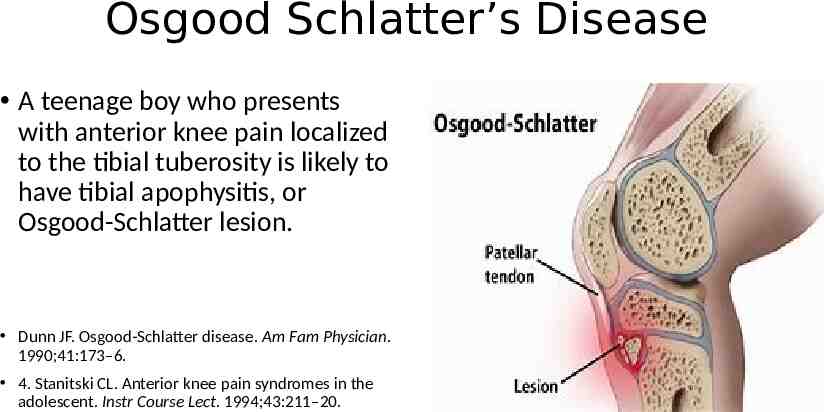

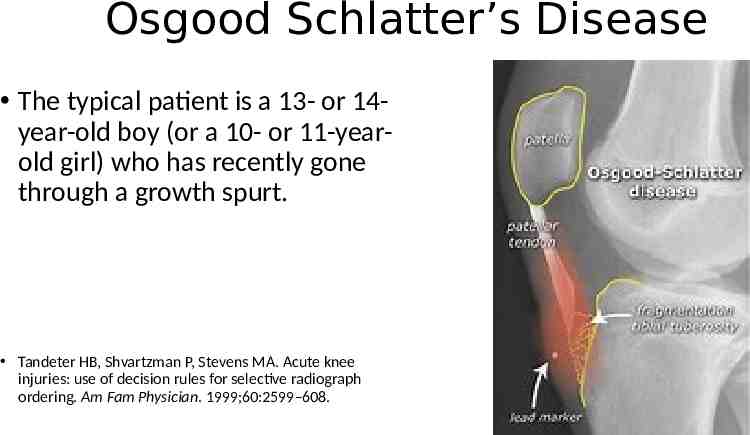

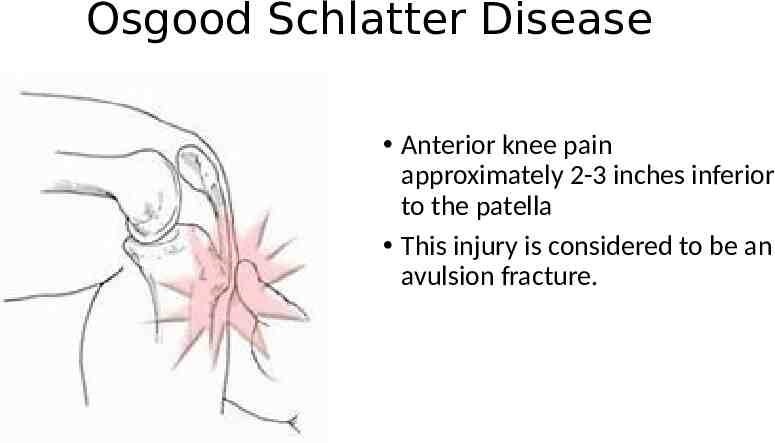

Osgood Schlatter Disease Usually an overuse type injury to the tibial tubercle apophyses Activity-related pain that is aggravated by jumping, squatting, and kneeling X-rays shows tubercle enlargement and fragmentation

Osgood Schlatter’s Disease A teenage boy who presents with anterior knee pain localized to the tibial tuberosity is likely to have tibial apophysitis, or Osgood-Schlatter lesion. Dunn JF. Osgood-Schlatter disease. Am Fam Physician. 1990;41:173–6. 4. Stanitski CL. Anterior knee pain syndromes in the adolescent. Instr Course Lect. 1994;43:211–20.

Osgood Schlatter’s Disease The typical patient is a 13- or 14year-old boy (or a 10- or 11-yearold girl) who has recently gone through a growth spurt. Tandeter HB, Shvartzman P, Stevens MA. Acute knee injuries: use of decision rules for selective radiograph ordering. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:2599–608.

Osgood Schlatter Disease Anterior knee pain approximately 2-3 inches inferior to the patella This injury is considered to be an avulsion fracture.

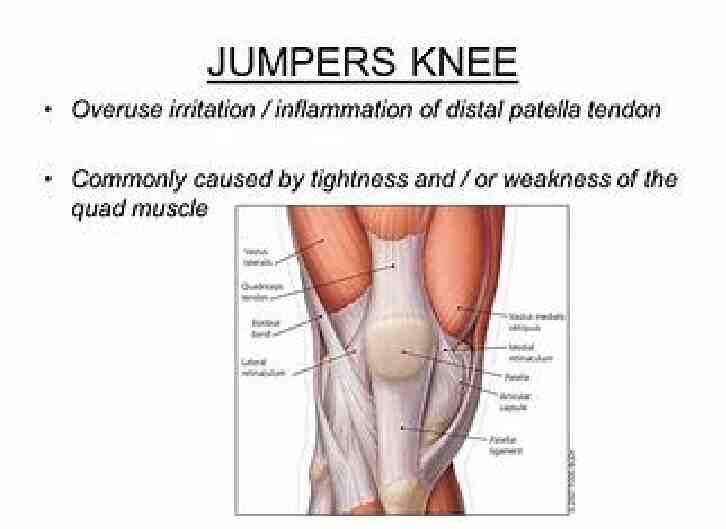

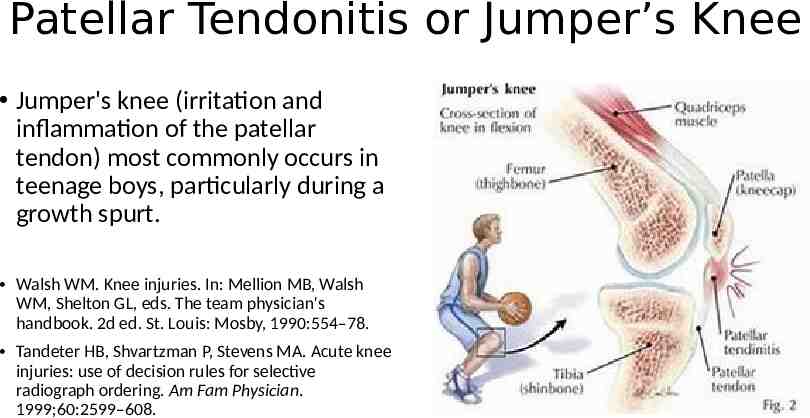

Patellar Tendonitis or Jumper’s Knee Jumper's knee (irritation and inflammation of the patellar tendon) most commonly occurs in teenage boys, particularly during a growth spurt. Walsh WM. Knee injuries. In: Mellion MB, Walsh WM, Shelton GL, eds. The team physician's handbook. 2d ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 1990:554–78. Tandeter HB, Shvartzman P, Stevens MA. Acute knee injuries: use of decision rules for selective radiograph ordering. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:2599–608.

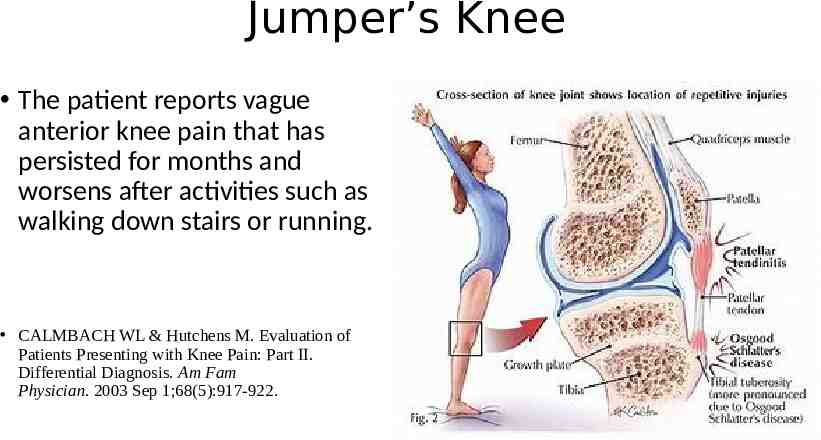

Jumper’s Knee The patient reports vague anterior knee pain that has persisted for months and worsens after activities such as walking down stairs or running. CALMBACH WL & Hutchens M. Evaluation of Patients Presenting with Knee Pain: Part II. Differential Diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Sep 1;68(5):917-922.

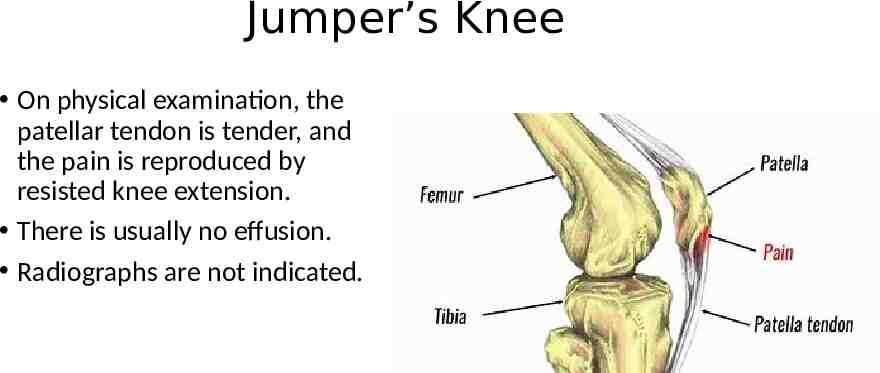

Jumper’s Knee On physical examination, the patellar tendon is tender, and the pain is reproduced by resisted knee extension. There is usually no effusion. Radiographs are not indicated.

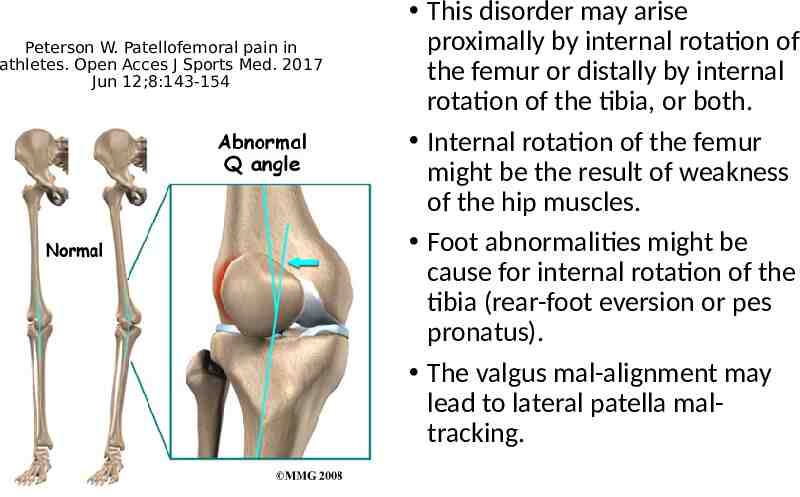

Peterson W. Patellofemoral pain in athletes. Open Acces J Sports Med. 2017 Jun 12;8:143-154 This disorder may arise proximally by internal rotation of the femur or distally by internal rotation of the tibia, or both. Internal rotation of the femur might be the result of weakness of the hip muscles. Foot abnormalities might be cause for internal rotation of the tibia (rear-foot eversion or pes pronatus). The valgus mal-alignment may lead to lateral patella maltracking.

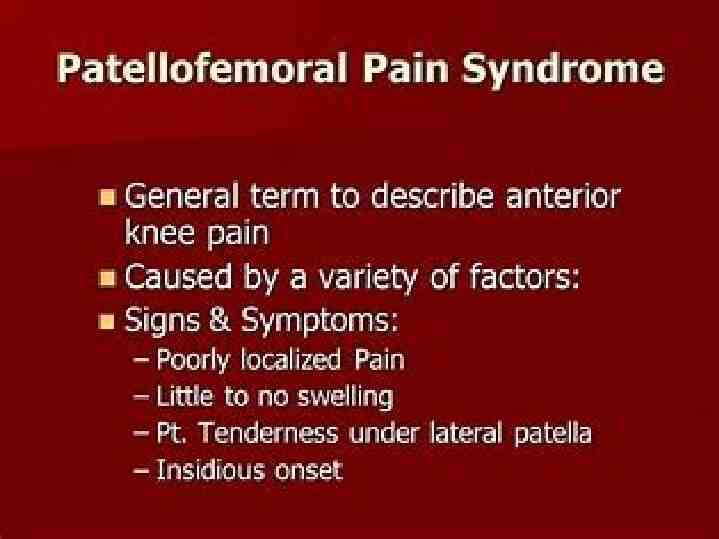

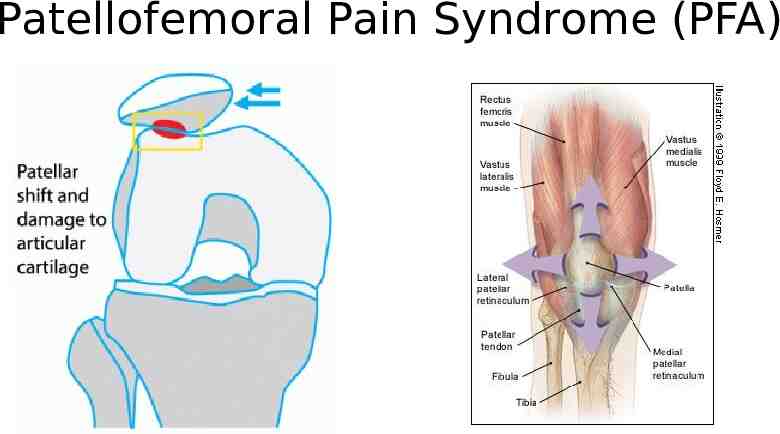

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFA) Runners Knee

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFA)

O Sign

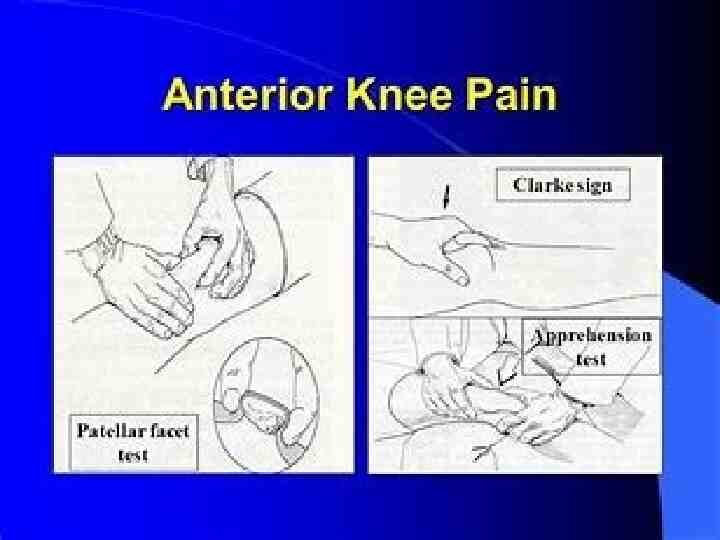

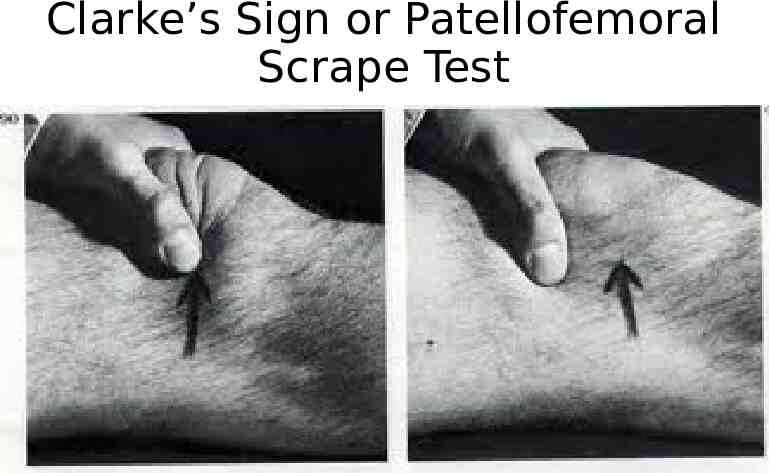

Clarke’s Sign or Patellofemoral Scrape Test

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFA) Runner’s Knee Chondromalacia Patellae

Internal Derangements of the Knee (IDK) IDK often means “I don’t know.”

Pain Characteristics The patient's description of knee pain is helpful in focusing the differential diagnosis. It is important to clarify the characteristics of the pain, including its onset (rapid or insidious), location (anterior, medial, lateral, or posterior knee), duration, severity, and quality (e.g., dull, sharp, achy). Aggravating and alleviating factors also need to be identified. If knee pain is caused by an acute injury, the physician needs to know whether the patient was able to continue activity or bear weight after the injury or was forced to cease activities immediately. Bergfeld J, Ireland ML, Wojtys EM, Glaser V. Pinpointing the cause of acute knee pain. Patient Care. 1997;31(18):100–7.

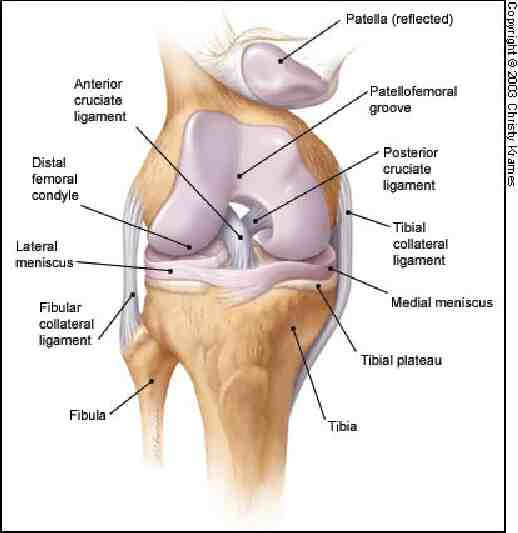

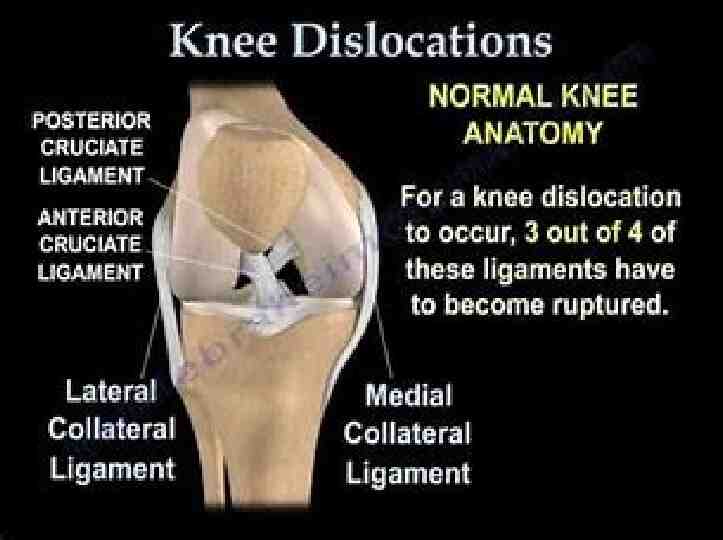

Mechanical Symptoms CALMBACH WL & Hutchens M. Evaluation of Patients Presenting with Knee Pain: Part I. History, Physical Examination, Radiographs, and Laboratory Tests. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Sep 1;68(5):907-912. The patient should be asked about mechanical symptoms, such as locking, popping, or giving way of the knee. A history of locking episodes suggests a meniscal tear. A sensation of popping at the time of injury suggests ligamentous injury, probably complete rupture of a ligament (third-degree tear). Episodes of giving way are consistent with some degree of knee instability and may indicate patellar subluxation or ligamentous rupture.

Effusion CALMBACH WL & Hutchens M. Evaluation of Patients Presenting with Knee Pain: Part I. History, Physical Examination, Radiographs, and Laboratory Tests. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Sep 1;68(5):907-912. The timing and amount of joint effusion are important clues to the diagnosis. Rapid onset (within two hours) of a large, tense effusion suggests rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament or fracture of the tibial plateau with resultant hemarthrosis, whereas slower onset (24 to 36 hours) of a mild to moderate effusion is consistent with meniscal injury or ligamentous sprain. Recurrent knee effusion after activity is consistent with meniscal injury.

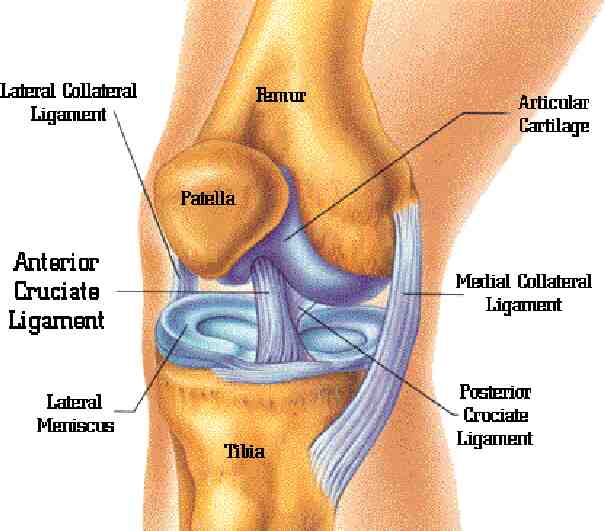

Mechanism of Injury CALMBACH WL & Hutchens M. Evaluation of Patients Presenting with Knee Pain: Part I. History, Physical Examination, Radiographs, and Laboratory Tests. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Sep 1;68(5):907-912. A direct blow to the knee can cause serious injury. Anterior force applied to the proximal tibia with the knee in flexion (e.g., when the knee hits the dashboard in an automobile accident) can cause injury to the posterior cruciate ligament. The medial collateral ligament is most commonly injured as a result of direct lateral force to the knee (e.g., clipping in football); this force creates a valgus load on the knee joint and can result in rupture of the medial collateral ligament. Conversely, a medial blow that creates a varus load can injure the lateral collateral ligament.

Mechanism of Injury CALMBACH WL & Hutchens M. Evaluation of Patients Presenting with Knee Pain: Part I. History, Physical Examination, Radiographs, and Laboratory Tests. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Sep 1;68(5):907-912. Noncontact forces also are an important cause of knee injury. Quick stops and sharp cuts or turns create significant deceleration forces that can sprain or rupture the anterior cruciate ligament. Hyperextension can result in injury to the anterior cruciate ligament or posterior cruciate ligament. Sudden twisting or pivoting motions create shear forces that can injure the meniscus. A combination of forces can occur simultaneously, causing injury to multiple structures.

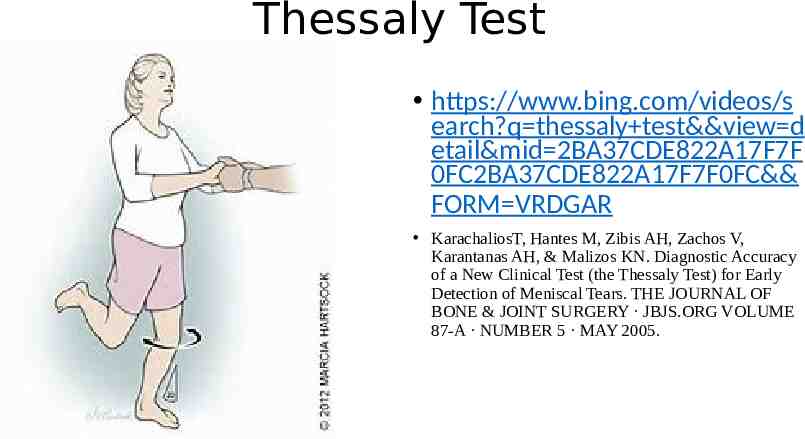

Thessaly Test https://www.bing.com/videos/s earch?q thessaly test&&view d etail&mid 2BA37CDE822A17F7F 0FC2BA37CDE822A17F7F0FC&& FORM VRDGAR KarachaliosT, Hantes M, Zibis AH, Zachos V, Karantanas AH, & Malizos KN. Diagnostic Accuracy of a New Clinical Test (the Thessaly Test) for Early Detection of Meniscal Tears. THE JOURNAL OF BONE & JOINT SURGERY · JBJS.ORG VOLUME 87-A · NUMBER 5 · MAY 2005.

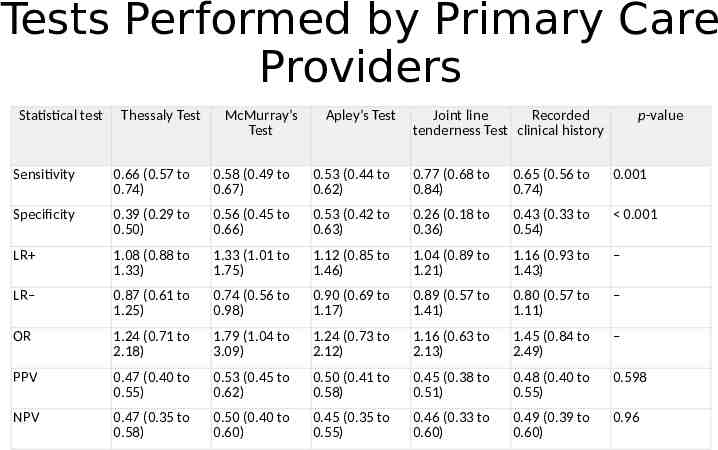

Tests Performed by Primary Care Providers Statistical test Thessaly Test McMurray’s Test Apley’s Test Joint line Recorded tenderness Test clinical history p-value Sensitivity 0.66 (0.57 to 0.74) 0.58 (0.49 to 0.67) 0.53 (0.44 to 0.62) 0.77 (0.68 to 0.84) 0.65 (0.56 to 0.74) 0.001 Specificity 0.39 (0.29 to 0.50) 0.56 (0.45 to 0.66) 0.53 (0.42 to 0.63) 0.26 (0.18 to 0.36) 0.43 (0.33 to 0.54) 0.001 LR 1.08 (0.88 to 1.33) 1.33 (1.01 to 1.75) 1.12 (0.85 to 1.46) 1.04 (0.89 to 1.21) 1.16 (0.93 to 1.43) – LR– 0.87 (0.61 to 1.25) 0.74 (0.56 to 0.98) 0.90 (0.69 to 1.17) 0.89 (0.57 to 1.41) 0.80 (0.57 to 1.11) – OR 1.24 (0.71 to 2.18) 1.79 (1.04 to 3.09) 1.24 (0.73 to 2.12) 1.16 (0.63 to 2.13) 1.45 (0.84 to 2.49) – PPV 0.47 (0.40 to 0.55) 0.53 (0.45 to 0.62) 0.50 (0.41 to 0.58) 0.45 (0.38 to 0.51) 0.48 (0.40 to 0.55) 0.598 NPV 0.47 (0.35 to 0.58) 0.50 (0.40 to 0.60) 0.45 (0.35 to 0.55) 0.46 (0.33 to 0.60) 0.49 (0.39 to 0.60) 0.96

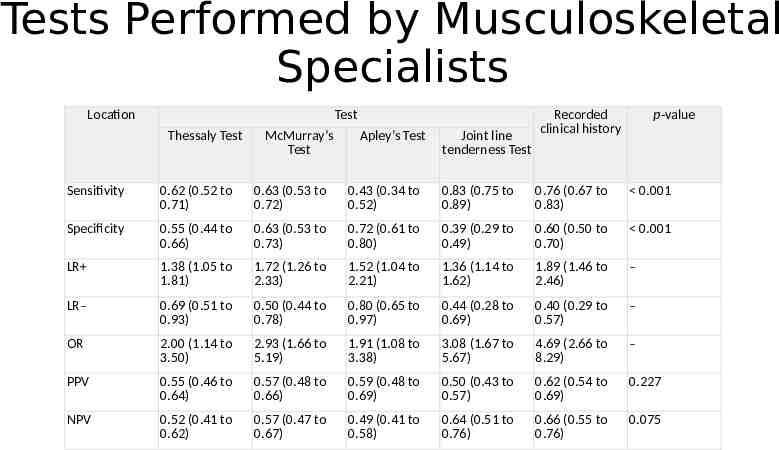

Tests Performed by Musculoskeletal Specialists Location Test Thessaly Test McMurray’s Test Apley’s Test Joint line tenderness Test Recorded clinical history p-value Sensitivity 0.62 (0.52 to 0.71) 0.63 (0.53 to 0.72) 0.43 (0.34 to 0.52) 0.83 (0.75 to 0.89) 0.76 (0.67 to 0.83) 0.001 Specificity 0.55 (0.44 to 0.66) 0.63 (0.53 to 0.73) 0.72 (0.61 to 0.80) 0.39 (0.29 to 0.49) 0.60 (0.50 to 0.70) 0.001 LR 1.38 (1.05 to 1.81) 1.72 (1.26 to 2.33) 1.52 (1.04 to 2.21) 1.36 (1.14 to 1.62) 1.89 (1.46 to 2.46) – LR– 0.69 (0.51 to 0.93) 0.50 (0.44 to 0.78) 0.80 (0.65 to 0.97) 0.44 (0.28 to 0.69) 0.40 (0.29 to 0.57) – OR 2.00 (1.14 to 3.50) 2.93 (1.66 to 5.19) 1.91 (1.08 to 3.38) 3.08 (1.67 to 5.67) 4.69 (2.66 to 8.29) – PPV 0.55 (0.46 to 0.64) 0.57 (0.48 to 0.66) 0.59 (0.48 to 0.69) 0.50 (0.43 to 0.57) 0.62 (0.54 to 0.69) 0.227 NPV 0.52 (0.41 to 0.62) 0.57 (0.47 to 0.67) 0.49 (0.41 to 0.58) 0.64 (0.51 to 0.76) 0.66 (0.55 to 0.76) 0.075

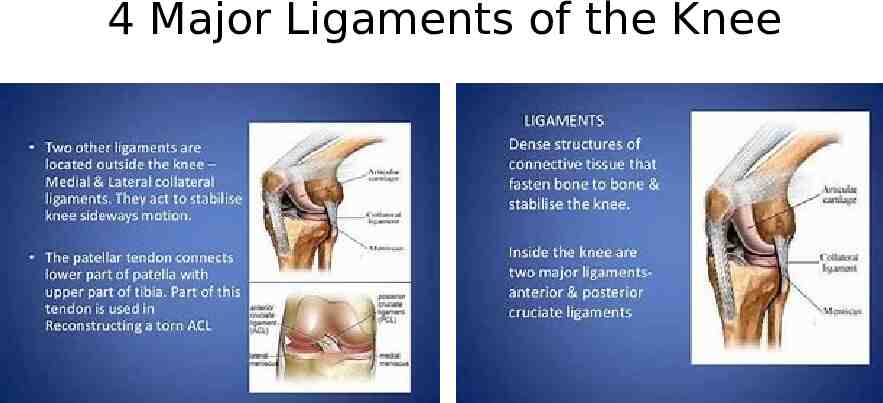

4 Major Ligaments of the Knee

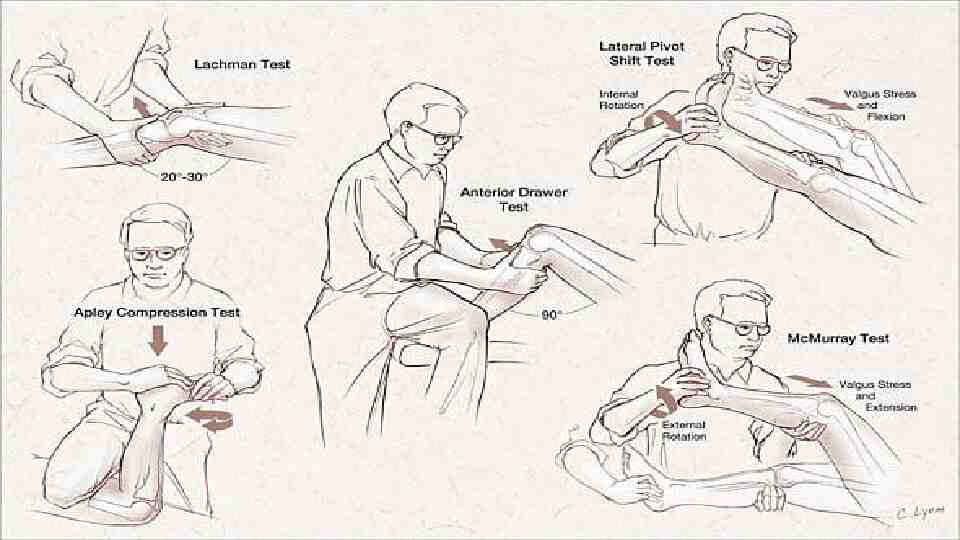

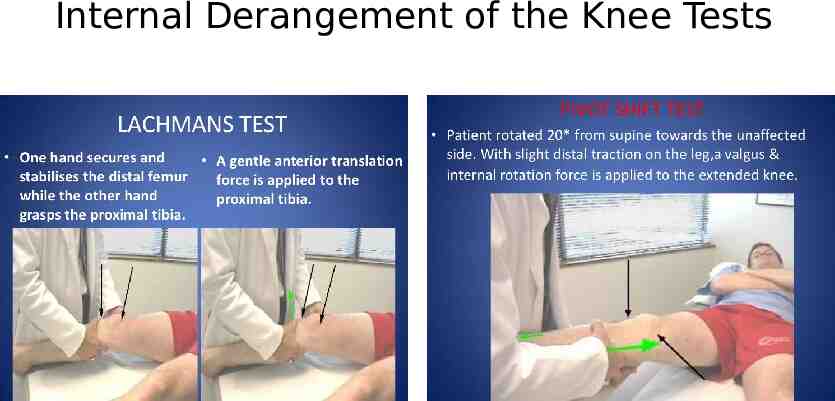

Internal Derangement of the Knee Tests

Lateral Pivot Shift Test for IDK A positive test may result in a gentle slide (Grade 1), or in a more severe jerk (Grade 2), or clunk (Grade 3). The grade of the pivot shift has been shown to correlate with patient-reported functional instability and clinical outcomes. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v cy20eA9qTlM

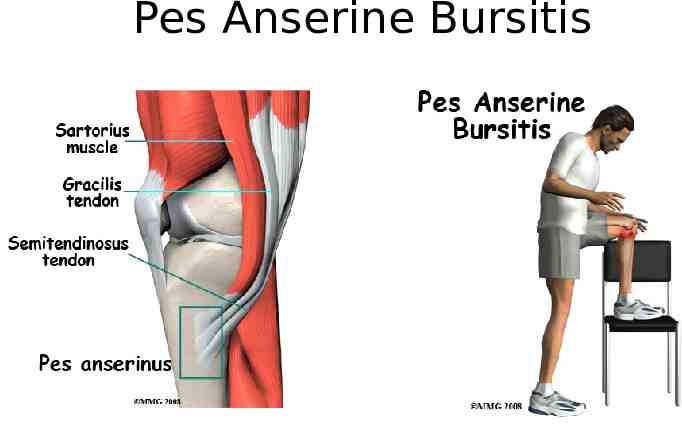

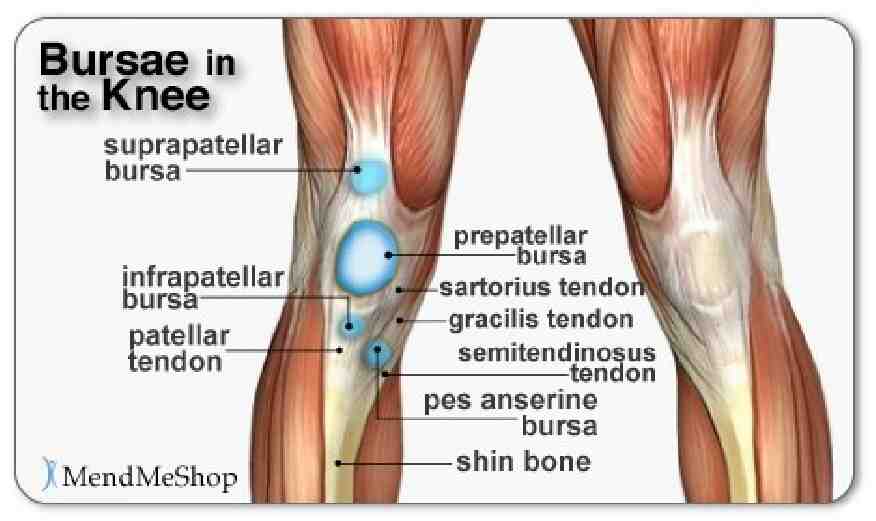

Pes Anserine Bursitis

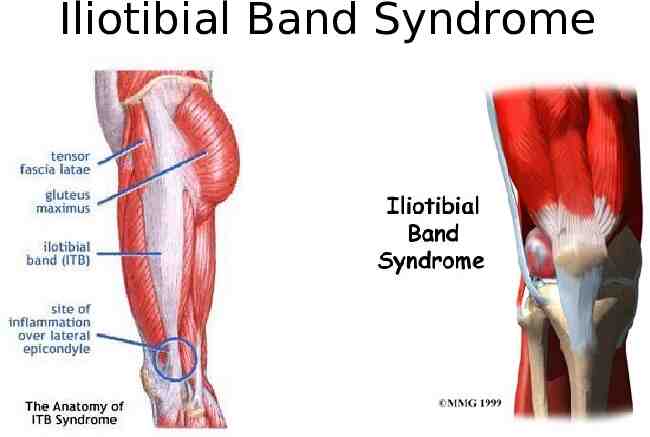

Iliotibial Band Syndrome

Iliotibial Pain Syndrome

Iliotibial Band Syndrome

References CALMBACH WL & Hutchens M. Evaluation of Patients Presenting with Knee Pain: Part I. History, Physical Examination, Radiographs, and Laboratory Tests. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Sep 1;68(5):907-912. CALMBACH WL & Hutchens M. Evaluation of Patients Presenting with Knee Pain: Part II. Differential Diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Sep 1;68(5):917-922. ROTH E, MIROCHNA M, and HARSHA D. Adolescent with Knee Pain. American Family Physician. Volume 86, Number 6 September 15, 2012 KarachaliosT, Hantes M, Zibis AH, Zachos V, Karantanas AH, & Malizos KN. Diagnostic Accuracy of a New Clinical Test (the Thessaly Test) for Early Detection of Meniscal Tears. THE JOURNAL OF BONE & JOINT SURGERY · JBJS.ORG VOLUME 87-A · NUMBER 5 · MAY 2005.