Marketing and Branding Strategies: The Use of Trademarks and

83 Slides1.27 MB

Marketing and Branding Strategies: The Use of Trademarks and Industrial Designs for Business Success; Case Studies Guriqbal Singh Jaiya Director SMEs Division, WIPO

Malaysian Textile Competition The dependence on contract manufacturing means that Malaysia is weak in terms of design and product planning capabilities, distribution and marketing capabilities. Instead of creating original Malaysian brands or names, Malaysian manufacturers produce for major world brand names, including: Adidas, Arnold Palmer, Active Wear, BUM Equipment, Calvin Klein, Christian Dior, Gucci, Guess, Donna Karan, YSL, Levi's, Nike, Padini, Polo, Ralph Lauren, Reebok, Slazenger, Pierre Cardin, Camel, Mizuno and Montagut.

Marketing and Product Differentiation DIFFERENTIATION is the act of designing a set of meaningful differences to distinguish the company’s offering from competitors’ offerings. - Kotler (1997)

Key Differentiating Factors for a New Product The product represents a functional improvement on competing or substitute products The retail-selling price is considered to be advantageous The product and/or its labeling has an attractive design The new product is properly branded, promoted and advertised The new product is readily available to customers in the main retail shops A number of after-sales services are provided that make the product appealing to consumers

How to Prevent Free Riding? If functional improvements, attractive designs and a well-positioned brand are some of the features that may determine the success of a new product, what can an SME do to protect them and maintain its exclusivity over their use?

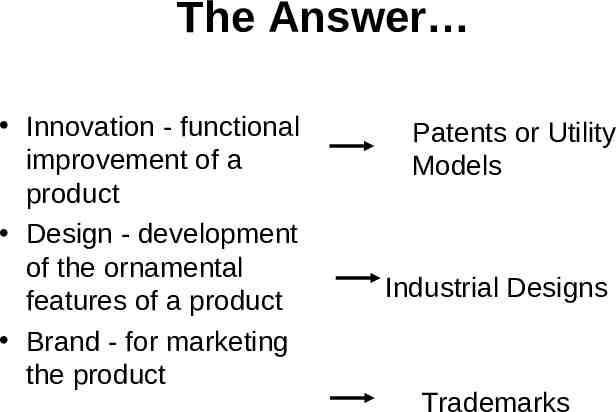

The Answer Innovation - functional improvement of a product Design - development of the ornamental features of a product Brand - for marketing the product Patents or Utility Models Industrial Designs Trademarks

Patent for the fountain pen that could store ink Utility Model for the grip and pippette for injection of ink Industrial Design: smart design with the grip in the shape of an arrow Trademark: provided on the product and the packaging to distinguish it from other pens Source: Japanese Patent Office

Corporate Image, Product Positioning and Brand Equity TRUST and RELATIONSHIPS are the bulwark of any enterprise, be it big or small, with a global or local ambit, having a traditional or modern management style, high tech or low tech, leader or follower, and irrespective of it being a part of the old world of ‘brick and mortar’ or a rising star reliant on e-commerce

Building Trust and Relationships A Brand is a consistent, holistic pledge made by a company, the face a company presents A Brand serves as an unmistakable symbol for products and services “Business card” a company proffers on the competitive scene to set itself apart from the rest

Trust is to Business, as Trademark is to Brand Brand Equity built on the foundation of a protected Trademark Brand/Trademark can: (a) be disposed off separately from other company assets (Free-standing Institutions); and (b) give rights that can be legally protected

Brand/Trademark Trademark: Legal concept Brand: Marketing concept Registration of a trademark adds value as it protects its other inherent assets Brand profile and positioning may vary over time, but trademark protection remains the same

WHAT IS A TRADEMARK? Any sign, or any combination of signs, capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings, shall be capable of constituting a trademark. Words including personal names, letters, numerals, figurative elements (logos), combination of colors, sounds, smells, etc Visually perceptible; 2D or 3D (shape) Graphic representation

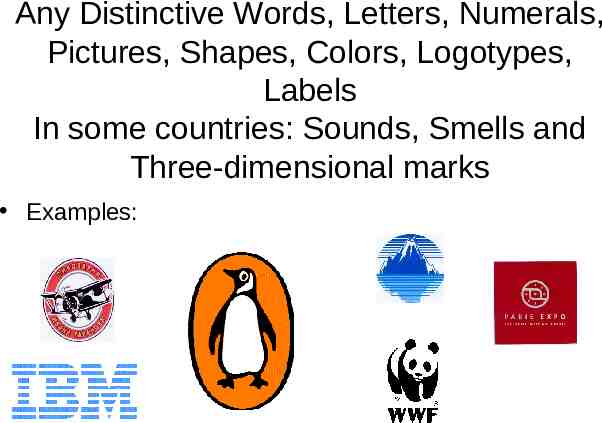

Any Distinctive Words, Letters, Numerals, Pictures, Shapes, Colors, Logotypes, Labels In some countries: Sounds, Smells and Three-dimensional marks Examples:

Definition of a Brand (1) Defines the differential features of a product or service: Real or Imaginary Rational or Irrational Tangible or Intangible

Definition of a Brand Contd. (2) Constitutes an image that creates a personal experience: Own Third party Imaginary

Definition of a Brand Contd. (3) With conscious and unconscious contents that the consumer projects and deposits on it; (4) Constitutes part of and builds up his/her identity; (5) Generates certain perceptions, attitudes and behaviors and enables fulfillment in their lives

Brand Identity Mind share (cognitive level) Heart Share (Emotional relationship) Buying intention share Self share (self-expression and selfdesign) Legend Share (cultural-sociological proposition; legendary; mythological)

Role of Brands: For the Company In a highly competitive world, where manufacturers are losing their pricing power, branding is seen as a way of clawing back some of the lost influence.

Role of Brands: For the Company Real and marketable asset Higher profit margin (Price Premium) Incremental cash flow Reduces cash flow sustainability risk

Role of Brands: For the Company Accelerates speed of cash flow Increases bonding and customer loyalty Increased market share Entry barrier Limits growth of competitors

Role of Brands: For the Company Requires lower investment levels Better negotiating position with trade and other suppliers Facilitates higher product availability (better distribution coverage) Dealers order what customers explicitly request

Role of Brands: For the Company Extends products’ life cycle Allows lower cost brand extensions Can be the basis for international expansion Provides legal protection; licensing; franchising Buffer to survive market or product problems

Role of Brands: For the Company Value of Brands is a key determinant of enterprise value and stock market capitalization Financial markets reward consistently focussed brand strategies Brand management a vital ingredient for success in corporate strategy

But. Brand Building Requires Time and Money; Brand Nourishing Should be a Continuous Process; Higher Profile/Exposure, Greater its Vulnerability; Can be Target of Counterfeiting/Criminal Activities;

Time required. “It took seven years of marketing before car buyers began to recognize that the BMW brand was distinctive”: Jorg Zintzmeyer, board member of Interbrand, p 33 of FORBES Global, July 22, 2002 in “The best-driven brand” by Nigel Hollway

So. The cost of building a brand can be very substantial over a period of time. That is why buying a brand sometimes makes sense to many companies.

Morgan Stanley’s Pettis Report on the relationship of corporate brand strategy and stock price shows that . “Smart strategies can result in stock price appreciation by 2 to 9%” “Positive Correlation between corporate improvements in brand strategy programs and a positive stock market return Starbucks: P/E ratio of 47!

The Importance of Brands “Consumers are starved for time and overwhelmed by the choices available to them. They want strong brands that simplify their decision making and reduce their risks” Are there other good reasons? Kevin Lane Keller, Tuck School of Business

Functions of a Trademark For the consumer: Enables consumers to distinguish between similar or identical products Products with characteristics that may not be examined prior to purchase Trademark as a guarantee of quality

Functions of Trademark For the company: – Enables it to differentiate its products – Basis for investing in the image and reputation of a company’s products – Consumers have emotional attachment to certain trademarks – Basis for a loyal clientele

The Value of a Trademark Interbrand conducts an annual survey of the most valuable trademarks in the world: Coca-cola: US 68.9 billon 52.7 bill. Microsoft : 65.1 bill. IBM:

The Value of a Trademark Consumers are willing to pay a premium price for a product bearing a trademark with a given reputation Mergers and acquisitions increasingly driven by need to acquire a trademark to, for example, enter a new market Companies outsourcing manufacturing activities to low-cost locations rely heavily on the trademarks as the main source of competitive advantage

Choosing a mark From a commercial point of view: – Short and simple – Easy to read, spell, pronounce and remember in all relevant languages – Not to have undesired connotations in any relevant language (“Nova”, “Traficante”, “Taco Bell”) – Easy to adapt to all advertising media

Choosing a mark Cannot be registered as trademarks: – Generic marks (cases “nylon”, “formica”, “aspirin”, etc) – Descriptive signs – Signs that may lead to confusion as to the nature of the product – Signs contrary to public order – Geographic signs – Signs that are similar or identical to existing registered trademarks

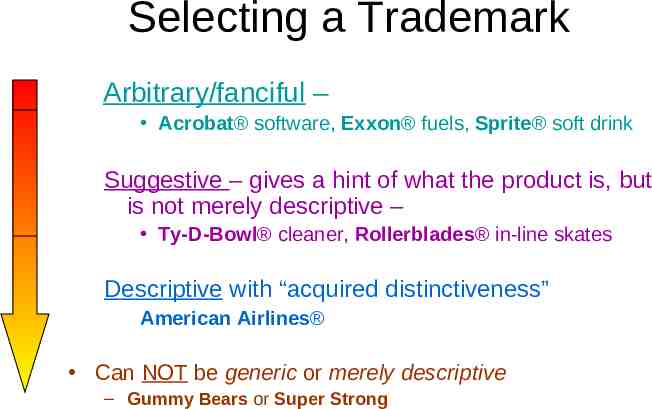

Selecting a Trademark Best choice: – Arbitrary/fanciful – Kodak film, Acrobat software, Exxon fuels – Suggestive – gives a hint of what the product is, but is not merely descriptive – Molyvan , Vancote Can not be generic or merely descriptive – ‘Super Strong’ – Diet Chocolate Fudge Soda – KANZEN TETSU

Selecting a Trademark Arbitrary/fanciful – Acrobat software, Exxon fuels, Sprite soft drink Suggestive – gives a hint of what the product is, but is not merely descriptive – Ty-D-Bowl cleaner, Rollerblades in-line skates Descriptive with “acquired distinctiveness” American Airlines Can NOT be generic or merely descriptive – Gummy Bears or Super Strong

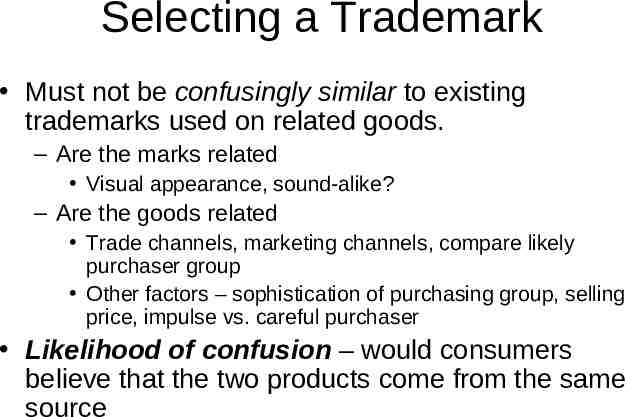

Selecting a Trademark Must not be confusingly similar to existing trademarks used on related goods. – Are the marks related Visual appearance, sound-alike? – Are the goods related Trade channels, marketing channels, compare likely purchaser group Other factors – sophistication of purchasing group, selling price, impulse vs. careful purchaser Likelihood of confusion – would consumers believe that the two products come from the same source

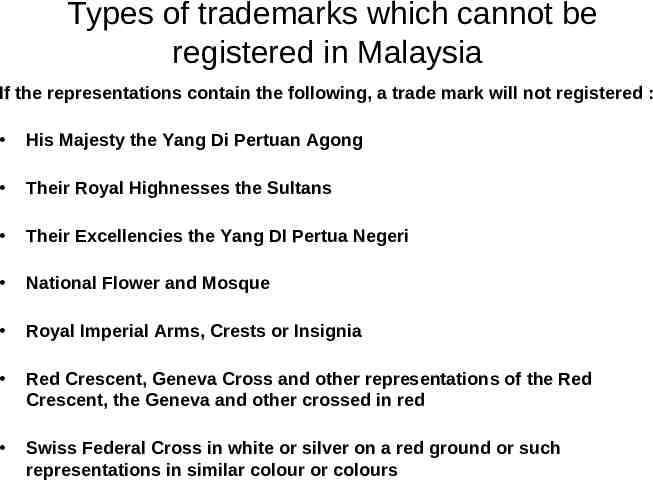

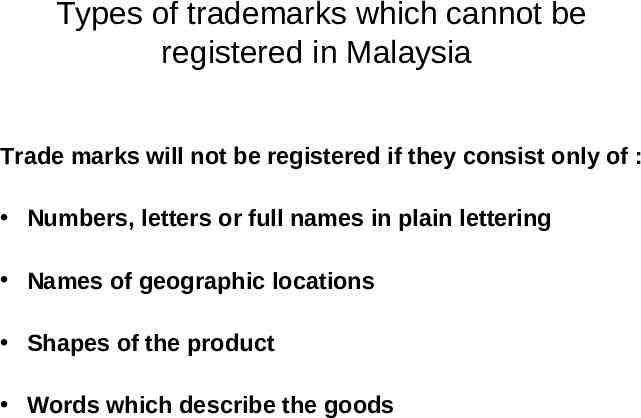

Types of trademarks which cannot be registered in Malaysia If the representations contain the following, a trade mark will not registered : His Majesty the Yang Di Pertuan Agong Their Royal Highnesses the Sultans Their Excellencies the Yang DI Pertua Negeri National Flower and Mosque Royal Imperial Arms, Crests or Insignia Red Crescent, Geneva Cross and other representations of the Red Crescent, the Geneva and other crossed in red Swiss Federal Cross in white or silver on a red ground or such representations in similar colour or colours

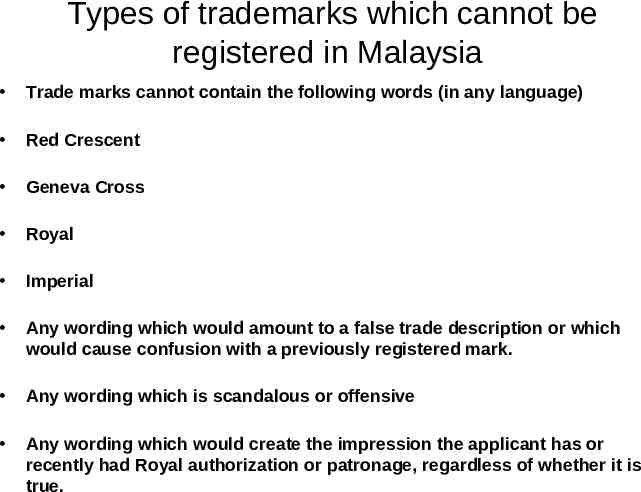

Types of trademarks which cannot be registered in Malaysia Trade marks cannot contain the following words (in any language) Red Crescent Geneva Cross Royal Imperial Any wording which would amount to a false trade description or which would cause confusion with a previously registered mark. Any wording which is scandalous or offensive Any wording which would create the impression the applicant has or recently had Royal authorization or patronage, regardless of whether it is true.

Types of trademarks which cannot be registered in Malaysia Trade marks will not be registered if they consist only of : Numbers, letters or full names in plain lettering Names of geographic locations Shapes of the product Words which describe the goods

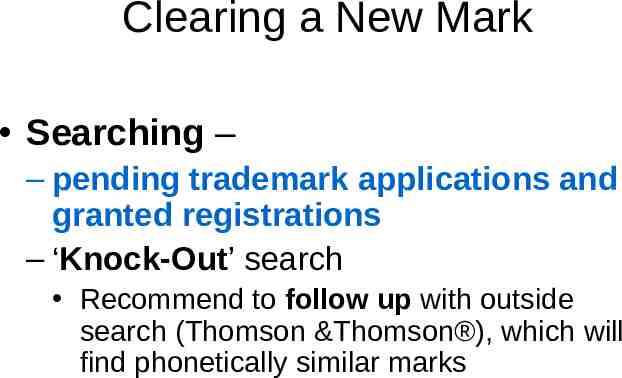

Clearing a New Mark Searching – – pending trademark applications and granted registrations – ‘Knock-Out’ search Recommend to follow up with outside search (Thomson &Thomson ), which will find phonetically similar marks

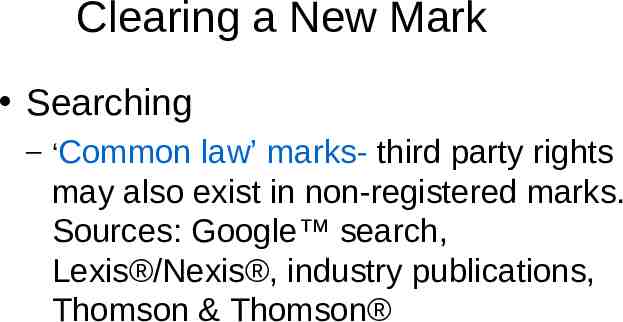

Clearing a New Mark Searching – ‘Common law’ marks- third party rights may also exist in non-registered marks. Sources: Google search, Lexis /Nexis , industry publications, Thomson & Thomson

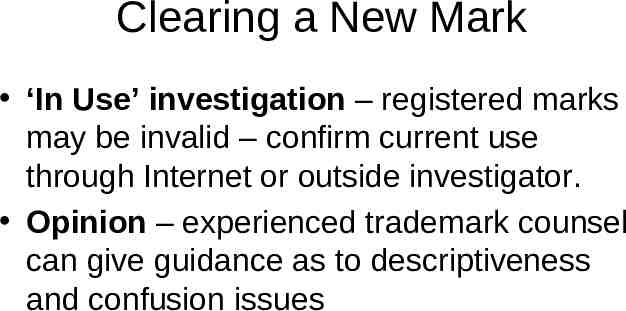

Clearing a New Mark ‘In Use’ investigation – registered marks may be invalid – confirm current use through Internet or outside investigator. Opinion – experienced trademark counsel can give guidance as to descriptiveness and confusion issues

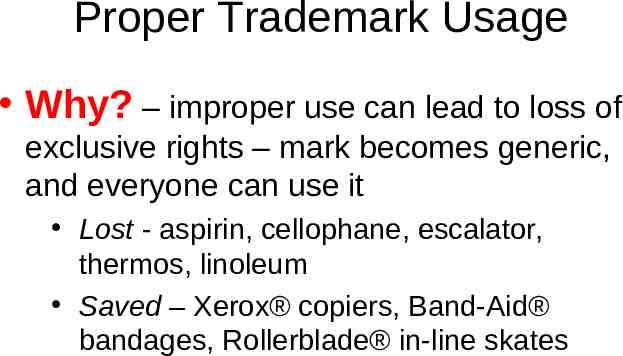

Proper Trademark Usage Why? – improper use can lead to loss of exclusive rights – mark becomes generic, and everyone can use it Lost - aspirin, cellophane, escalator, thermos, linoleum Saved – Xerox copiers, Band-Aid bandages, Rollerblade in-line skates

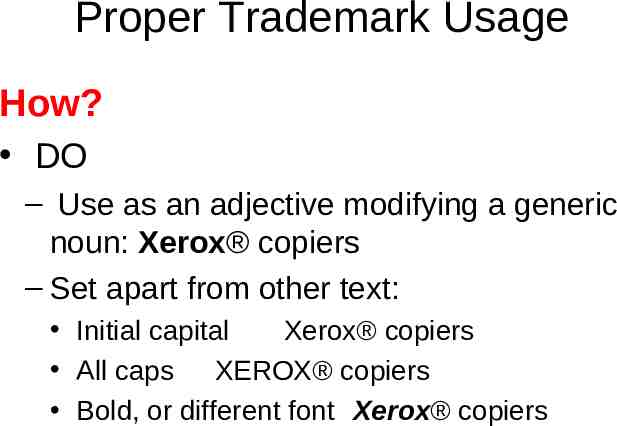

Proper Trademark Usage How? DO – Use as an adjective modifying a generic noun: Xerox copiers – Set apart from other text: Initial capital Xerox copiers All caps XEROX copiers Bold, or different font Xerox copiers

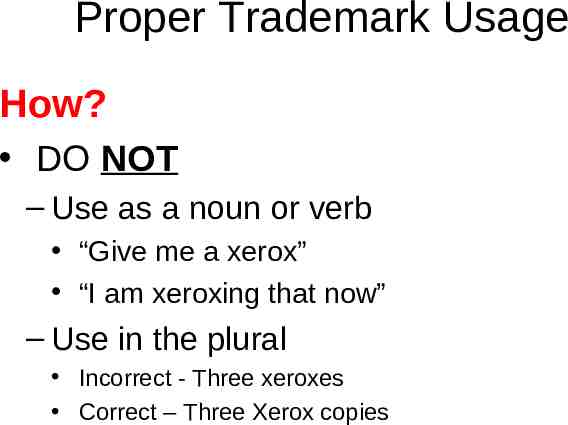

Proper Trademark Usage How? DO NOT – Use as a noun or verb “Give me a xerox” “I am xeroxing that now” – Use in the plural Incorrect - Three xeroxes Correct – Three Xerox copies

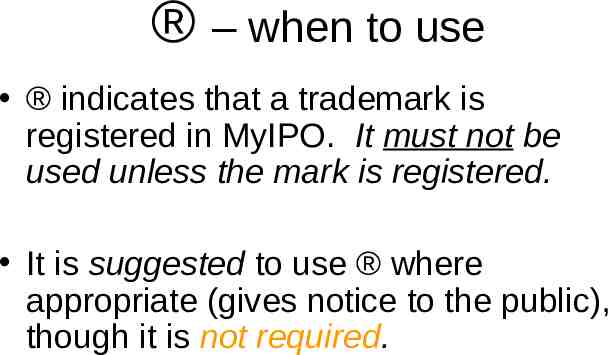

– when to use indicates that a trademark is registered in MyIPO. It must not be used unless the mark is registered. It is suggested to use where appropriate (gives notice to the public), though it is not required.

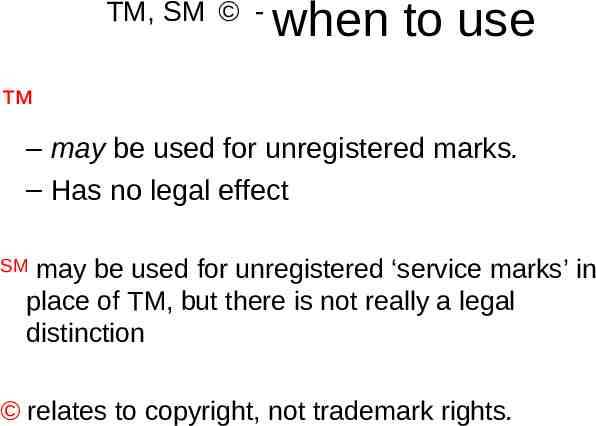

TM, SM - when to use – may be used for unregistered marks. – Has no legal effect may be used for unregistered ‘service marks’ in place of TM, but there is not really a legal distinction SM relates to copyright, not trademark rights.

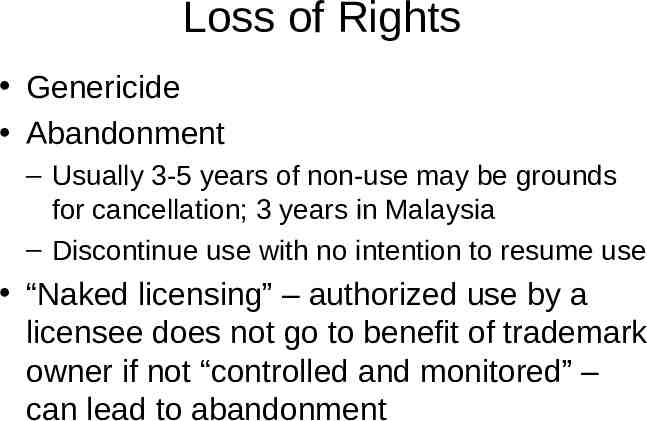

Loss of Rights Genericide Abandonment – Usually 3-5 years of non-use may be grounds for cancellation; 3 years in Malaysia – Discontinue use with no intention to resume use “Naked licensing” – authorized use by a licensee does not go to benefit of trademark owner if not “controlled and monitored” – can lead to abandonment

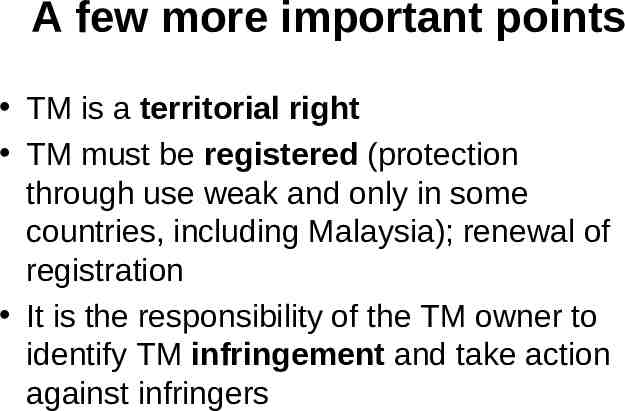

A few more important points TM is a territorial right TM must be registered (protection through use weak and only in some countries, including Malaysia); renewal of registration It is the responsibility of the TM owner to identify TM infringement and take action against infringers

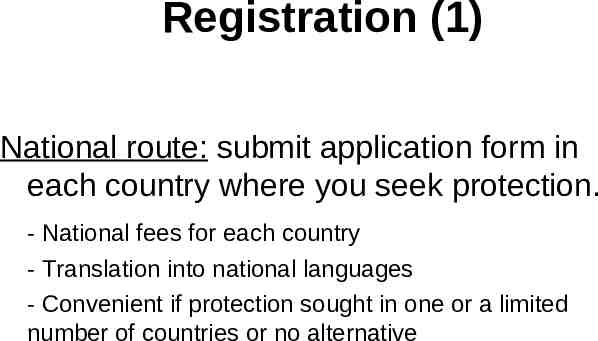

Registration (1) National route: submit application form in each country where you seek protection. - National fees for each country - Translation into national languages - Convenient if protection sought in one or a limited number of countries or no alternative

Registration (2) Regional route: use regional trademark systems for protection in several countries. - African Intellectual Property Organization (OAPI): www.oapi.wipo.net - African Regional Industrial Property Organization (ARIPO): www.aripo.org - Benelux Trademark Office - Office for the Harmonization of the Internal Market (OHIM): trademark office for countries that are members of the European Union. Http://oami.eu.int

Registration (3) International route: Madrid system for the international registration of marks - One application - One language - One set of fees - 77 member states - Administered by WIPO - One system, two treaties

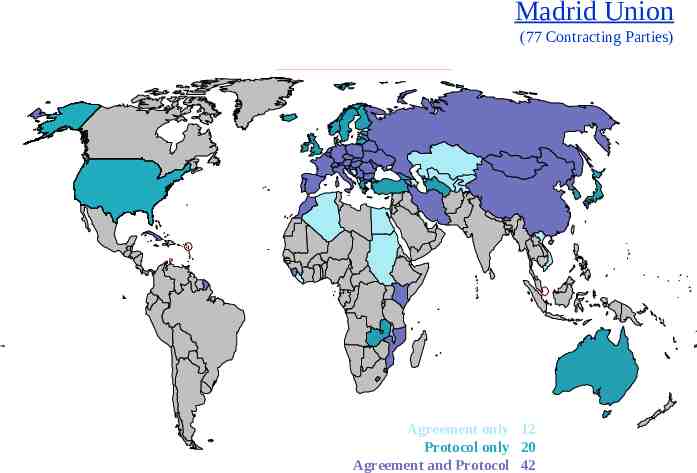

Madrid Union (77 Contracting Parties) Agreement only 12 Protocol only 20 Agreement and Protocol 42

Case study: Pickwick An Italian businessman buys unmarked t-shirts from manufacturers of generic clothing, attaches his trademark and begins to sell them to retail stores Started in a garage in the periphery of Rome Today the Pickwick trademark is perceived by Italian teenagers as a synonym of style and quality Pickwick exports its products across Europe Its trademark is considered its most valuable asset.

GRINGO Case Study A Mozambiquian Success Story.

ZARA Case Study In Industria De Diseno Textil SA v Edition Concept Sdn Bhd ([2005] 2 CLJ 357) the defendant applied to amend the Trademarks Register to expunge the plaintiff’s ZARA mark on the grounds that: the ZARA mark was wrongly entered in the register as its use was likely to deceive or cause confusion to the public because the ZARA mark is well known in Malaysia as a result of the defendant’s alleged use of it since September 1999; and there had been no use of the ZARA mark during its registration by the plaintiff for a continuous period of three years up to one month before the application for rectification was filed. In dismissing the first ground, the High Court held that the correct date in determining whether the mark was well known in Malaysia was the date of application for registration of the ZARA mark by the plaintiff (ie, August 3 1998). The defendant failed to adduce any evidence that the ZARA mark was well known in Malaysia on this date. In dismissing the second ground, the High Court held that the correct date when calculating whether there had been non-use of the ZARA mark during its registration for a continuous period of three years was the date the mark was actually entered upon the register (ie, February 5 2002) and not the date of application for registration. Therefore, the three-year period should run from February 5 2002 and not August 3 1998. The High Court found that the plaintiff had started using the ZARA mark 10 months before the rectification proceedings were filed by the defendant; hence the defendant failed to satisfy the requirement of non-use for a continuous period of three years. The High Court recognised the importance of trademark searches to avoid unnecessary litigation and their significance in commercial and business decisions. The High Court remarked that the defendant should have carried out a trademark search at the Registry

Looking at Designs Looking Good

Purpose of Design – Make your product appealing to consumers – Create a « niche » market – Customize products in order to target different customers (e.g. Swatch) – Develop the brand (e.g. Apple ’s « Think Different » strategy)

Two-dimensional Designs

Three-Dimensional Designs

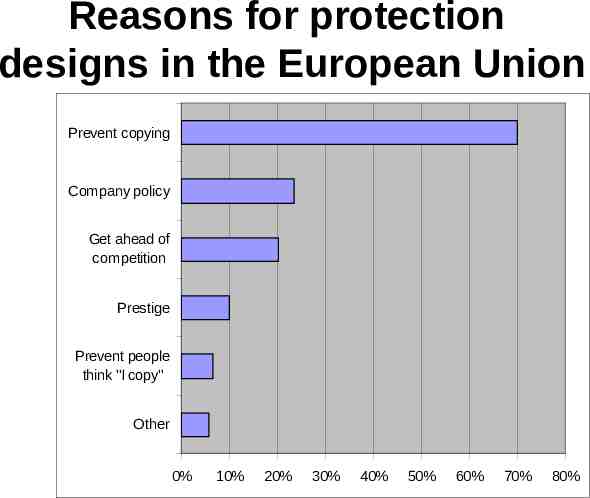

Reasons for protection designs in the European Union Prevent copying Company policy Get ahead of competition Prestige Prevent people think "I copy" Other 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80%

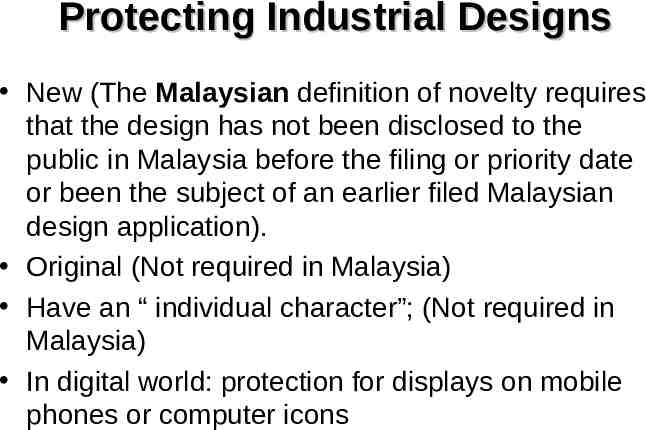

Protecting Industrial Designs New (The Malaysian definition of novelty requires that the design has not been disclosed to the public in Malaysia before the filing or priority date or been the subject of an earlier filed Malaysian design application). Original (Not required in Malaysia) Have an “ individual character”; (Not required in Malaysia) In digital world: protection for displays on mobile phones or computer icons

Protecting Industrial Designs In Malaysia, the definition of a protectible design refers to features of shape, configuration, pattern, or ornament applied to an article by an industrial process or means, being features which in the finished article appeal to and are judged by the eye, but does not include: (a) a method or principle of construction; or (b) features of shape or configuration of an article which: (i) are dictated solely by the function which the article has to perform; or (ii) are dependent on the appearance of another article of which the article is intended by the author of the design to form an integral part. Designs which are contrary to public order or morality are not capable of protection. However, there is no requirement for any degree of creativity or originality beyond the design being new.

Industrial Design Protection Industrial designs are compositions of lines or colors or any three-dimensional forms which give a special appearance to a product They protect the ornamental or aesthetic aspect of a product Exclusive rights: Right to prevent others from applying (making, selling or importing) the protected design to commercial products for a period of 10 to 25 years; 15 yrs in Malaysia (except in some cases) Requirement of registration (new EU legislation includes unregistered design protection) Section 27 of the Industrial Designs Act 1996 provides for grant of a compulsory licence if there has been no reasonable industrial application of the registered design.

Industrial Design Protection The IDA of Malaysia provides a right of action for infringement of a registered design but no criminal offences. An action must be brought within a limitation period of 5 years from the date of infringement. A defence of innocent infringement is available to an infringer who proves that he was unaware that the design was registered.

Extending UK Designs to Malaysia With the Industrial Designs Act coming into force in 1 September 1999, Malaysian industrial design registrations are valid only for a total of only 15 years, with 2 renewal periods. The Registrar of Industrial Designs issued a Directive stating that the 4th and 5th term extensions of the extended UK design registrations are not applicable in Malaysia, thereby limiting the extended UK design registrations to a maximum validity of 15 years instead of the original 25-years. As a result, a legal suit (Shachihata & 18 Ors v. Registrar of Industrial Designs & Ors) was brought to determine the above issue. The High Court of Malaya ruled that the Industrial Designs Registration Office should by law accept applications for renewal of the fourth and fifth renewal period for UK registered industrial designs that were registered after 01 August 1989 but before 01 September 1999. This will mean that the period of the pre-1999 industrial design filed under the UK Registered Designs Act 1949 will be applicable for the full 25 year period in Malaysia. The Registrar of Industrial Designs has therefore withdrawn the earlier Directive and has issued a New Directive which states that 4th and 5th period extensions are now allowed (with conditions). The official fee payable for the subsequent 4th and 5th term of the extended industrial design has not yet been determined by the Registrar. They have indicated however that they are currently accepting renewal documentation for the 4th and 5th period extensions, and full renewal documentation should be provided to them first, to be followed by payment of the official fee upon announcement of the said fee.

The design needs to be new and/or original. Do these qualify?

Registering designs abroad National route Regional route: – Office for the Harmonization of the Internal Market (OHIM): industrial designs office of the European Union International route: – The Hague Agreement

States party to the Hague Agreement as of (Total 37) Germany Belgium Belize Bulgaria Ivory Coast Croatia Spain Estonia Macedonia Gabon Georgia Greece Hungary Indonesia Iceland Italy Liechtenstein Luxembourg Morocco Mongolia Netherlands Moldova Holy See Senegal Slovenia Suriname Tunisia Ukraine Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Serbia and Montenegro Benin Egypt France Kyrgyzstan Monaco Romania Switzerland

Case Study: TRAX Trax is a system of public seating manufactured by OMK Design Ltd. Originally designed for British Rail. Had to be visually appealing, comfortable and weather-resistant In 1990, installed in railway stations in UK 15 years later, installed in over 60 airports Industrial design protection in UK, France, Germany, Italy, Benelux, Australia and the US has guaranteed a degree of exclusivity keeping imitators away

Honda Case Study In Honda Giken Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha v Allied Pacific Motor ([2005] 3 MLJ 30) Honda applied for an interlocutory injunction against the defendant based on the alleged infringement of: five industrial design registrations owned by Honda for the Honda Wave 125 motorcycle by the defendant’s Comel Manja JMP 125 motorcycle; and Honda’s copyright in two and three-dimensional drawings of the Honda EX5 Dream motorcycle by the defendant’s Comel Manja JMP 100 motorcycle. The designs were registered on December 7, 2000. The drawings were created by Honda in Japan and first published in Thailand. In dismissing the defendant’s contention that the designs were not new as vehicles of a similar design had been sold in Thailand prior to the plaintiff’s application to register the designs in Malaysia, the High Court ruled that the novelty requirement in the Industrial Designs Act 1996 is territorial. Therefore, prior disclosure of designs outside Malaysia is irrelevant. The court also applied the statutory presumption under Section 114(e) of the Evidence Act 1950 that official acts have been correctly carried out. Therefore, the court held that the designs were valid, ruling that there were many similarities between the Honda Wave 125 and the defendant’s JMP 125. In dealing with the copyright claim, the court applied the Copyright (Application to Other Countries) Regulations 1990 and held that the drawings first published in Thailand were entitled to copyright protection in Malaysia (subject to eligibility under the Copyright Act 1987). The court stated that the drawings were protected by copyright as artistic works in Malaysia and were similar to the eventual product of the JMP 100 motorcycle. Although the court concluded that there were serious questions to be tried, it stated that the balance of convenience tilted in favour of refusal of the grant of an interlocutory injunction. The court found that the grant of an injunction pending final disposal of the suit would have a negative and perhaps irreversible impact on the defendant, as an injunction would affect third parties and the government.

Honda Case Study Contd. Interestingly, in considering the copyright claim, Section 7(6) of the Copyright Act 1987 was neither raised nor dealt with by the court. Section 7(6) protects designs that are capable of being registered under the Industrial Designs Act 1996 but are not registered. However, copyright for such designs ceases as soon as any article to which the design has been applied is reproduced more than 50 times by an industrial process. Based on decisions of the Privy Council and the Australian courts, which are regarded as persuasive in Malaysia, ‘capable of registration’ has been interpreted to mean that the design falls within the definition of an ‘industrial design’ under the relevant industrial design laws, and that it does not need to be new. However, there are no reported Malaysian cases dealing with this phrase. An ‘industrial design’ covers features of shape, configuration, pattern or ornament applied to an article by any industrial process, being features that, in the finished article, appeal to and are judged by the eye. Designs that are not capable of registration under the Industrial Designs Act 1996 but that are artistic works within the meaning of the Copyright Act 1987 enjoy copyright protection for 25 years from the time the design is exploited by the copyright owner or licensee by making articles by an industrial process as copies of the artistic work and marketing such articles in Malaysia or elsewhere. The two and three-dimensional drawings of the Honda EX5 Dream motorcycle were protected by copyright as artistic works that are not capable of registration, although technically such drawings were capable of registration under the Industrial Designs Act 1996. If the latter applied, copyright in such drawings would cease as soon as the motorcycle (the Honda EX5) to which the design is applied had been reproduced more than 50 times.

Concept of Novelty in Malaysia The recent Malaysian decision of CKE Marketing Sdn Bhd v Virtual Century Sdn Bhd [2006] 1 MLJ 767, set out that the design concerned must be looked at as a whole, when comparisons are made with the prior art and that any evidence of prior art has to be strictly proven. The facts of the case In this case, the first defendant’s industrial design which was filed on 12 August, 1999 pertained to the design of a glass door display chiller / freezer sold under the brand name of LINDEN, termed as “Refrigeration Apparatus” under the provision of the Industrial Designs Act 1996. The First Defendant’s Design The plaintiff applied for rectifying the Register of Industrial Designs contending that the Defendant’s industrial design registration had wrongfully remained on the Designs Register due to disclosure made to the Malaysian public prior to the said 12 August, 1999 priority date due to the existence of other designs differing only in immaterial details. The first defendant claimed that the existing models and design features of the refrigeration apparatus that existed prior to the date of the defendants’ design application were old and unappealing in appearance and, therefore, based on their background knowledge of the industry, the first defendant developed novel design features and applied it to its product and sold its new product in the market. The main features, which the first defendant contended were novel, were a curved crescent like shape, display panel with aluminum frames and curved aluminum doorframes. The defendant’s design registration was further bolstered by a registered design, which the defendant had obtained under the UK Registered Design’s Act 1949.

Concept of Novelty in Malaysia The findings of the court The High Court followed the requirements of novelty as set out in the English Court of Appeal decision of AMP Incorporated v Utilux Pty Ltd [1970] RPC 397 which held that there must be substantial novelty or originality having regard to the nature of the article before it is registrable, and differences from the prior art in details which are immaterial are not enough reason to expunge a design registration. The question of differences in a particular case would depend on the nature of the article, the extent of the prior art, and the number of previous designs in the field in question. In view of the above, the court held that the question of novelty is dependent on the nature of the article and that a relevant consideration would be whether the article is a generic product that is commonly used by members of the public. In such circumstances, it is likely that the design features applied to an article are already individually in existence or in use prior to the formation of the said article. The paramount consideration for the court will be the totality of the design features taken as a whole and the overall appearance of the common article as compared with the articles that were disclosed to the public earlier. The court also held that in relation to generic and common products the standard of novelty must be construed in accordance with the circumstances and followed the English decision of D Sebel & co Ltd v National Art Metal Pty Ltd [1965] 10 FLR 224.

Concept of Novelty in Malaysia Comparison of Designs In this case, the statement of novelty read: Novelty Resides In The Shape And Configuration Of The Design As Shown In The Circle In The Representations” and was accompanied by front and perspective photograph of the first defendant’s article as a whole with a side view photograph of the curved panel marked as circle A and a front view photograph of a curved panel marked as circle B to illustrate visual details. In this respect, the court held that the plaintiff’s attempt to isolate each of the designs marked as circles A and B in the design registration and compare the same individually against purported prior art was wholly misleading and incorrect in law. This is as the appealing appearance of the first defendant’s article was a result of a combination of a crescent like display with curved aluminum border frames and the door frames having a distinctive curve at the center with the two grooves forming its border. Therefore, when both the articles of the defendants as well as the plaintiff were viewed, the Judge held that there were sufficient and material differences between both the articles in question. The first defendant had taken reasonable amount of steps to illustrate the characteristics in the design that would naturally enhance or have impact on the visual appearance or appeal of the first defendant’s article.

Concept of Novelty in Malaysia Evidence of Prior Art The court also held that there was no cogent evidence of the prior art as there was only a letter by a foreign company stating that a certain model of refrigerator was introduced into the Malaysian market in 1993 which the court found to be hearsay and it did not prove that the design concerned was disclosed to the Malaysian public at that time. As to a collection of sales brochures and a directory, this was also not accepted by the court as evidence of disclosure to the public. Therefore, any evidence of disclosure has to be direct and cogent such as the sale of the infringing article before the court accepts the same. In addition, the court held that although evidence of exports of a certain product or article can be shown in Malaysia, this would not be sufficient or cogent evidence that the product has been disclosed to the public. Conclusion The stand taken by the Malaysian High Court suggests that the issue of novelty has to be viewed in great detail and not plainly on a surface level. Accepting de minimis differences nor trade variants based on the slightest aspect of the article as was highlighted in the above decision in question would not be sufficient to argue that a design does not hold novelty. The case holds firm that the issue of novelty of a design cannot just be viewed or examined on the minute details of the article alone but must also be examined as a whole and overall features of the article itself. The court will not view the article in isolation but rather view it as a whole. The court was therefore right to rule that the plaintiff’s attempt to isolate each of the designs from the first defendant’s article was wholly misleading and incorrect in law.