DISTINCTIVE FEATURES OF POETRY Ppt. by B.TING Material from

21 Slides1.82 MB

DISTINCTIVE FEATURES OF POETRY Ppt. by B.TING Material from Sara Thorne’s Mastering Poetry

Distinctive Features of Poetry Identifying them is only a starting point – of most importance is an exploration of the effects that are created and the way these influence the reader. It is useful to recognize the distinctive features of poetry because they have an effect on the way in which poets create meaning.

EndStopped Lines

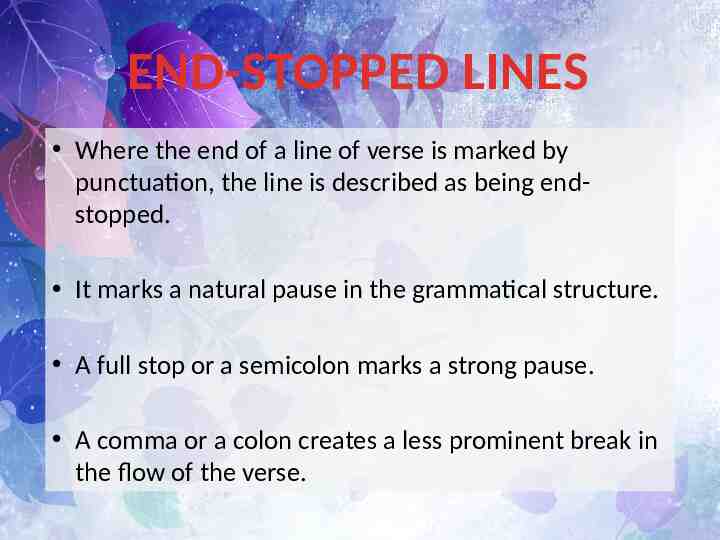

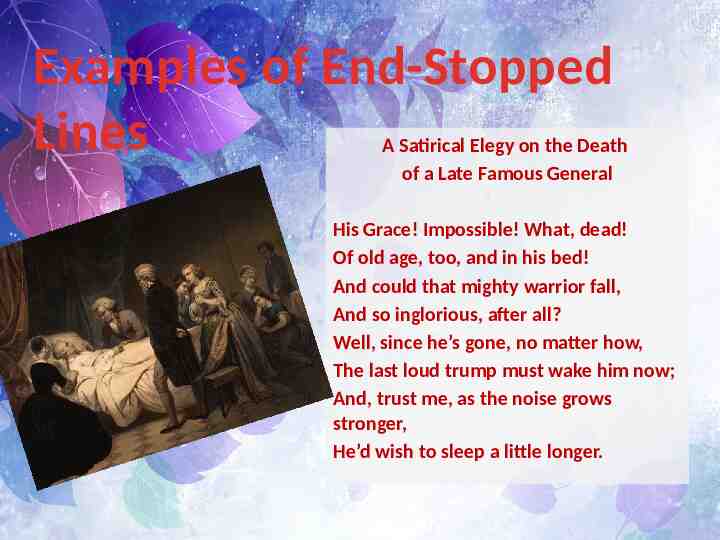

END-STOPPED LINES Where the end of a line of verse is marked by punctuation, the line is described as being endstopped. It marks a natural pause in the grammatical structure. A full stop or a semicolon marks a strong pause. A comma or a colon creates a less prominent break in the flow of the verse.

Examples of End-Stopped Lines A Satirical Elegy on the Death of a Late Famous General His Grace! Impossible! What, dead! Of old age, too, and in his bed! And could that mighty warrior fall, And so inglorious, after all? Well, since he’s gone, no matter how, The last loud trump must wake him now; And, trust me, as the noise grows stronger, He’d wish to sleep a little longer.

Enjambment

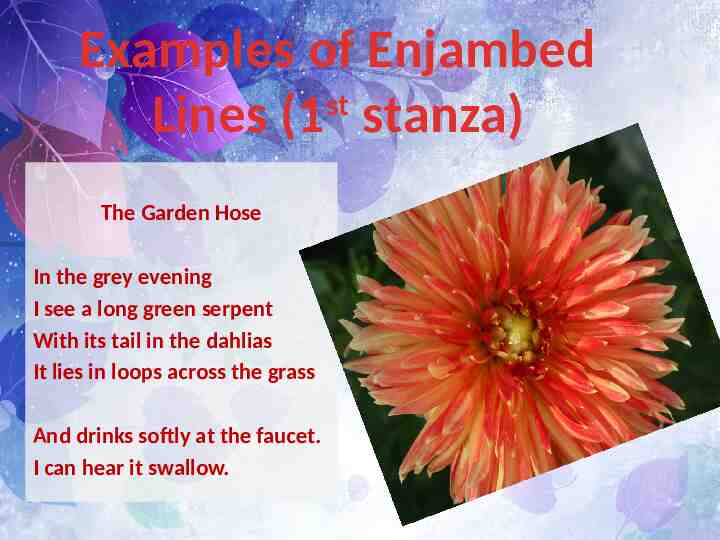

ENJAMBMENT Enjambed lines are not marked by punctuation because the grammatical structures are not completed within one line of verse. The meaning is continued across line boundaries and the reader must, therefore, read on in order to understand what a poet is saying.

Examples of Enjambed st Lines (1 stanza) The Garden Hose In the grey evening I see a long green serpent With its tail in the dahlias It lies in loops across the grass And drinks softly at the faucet. I can hear it swallow.

Caesura

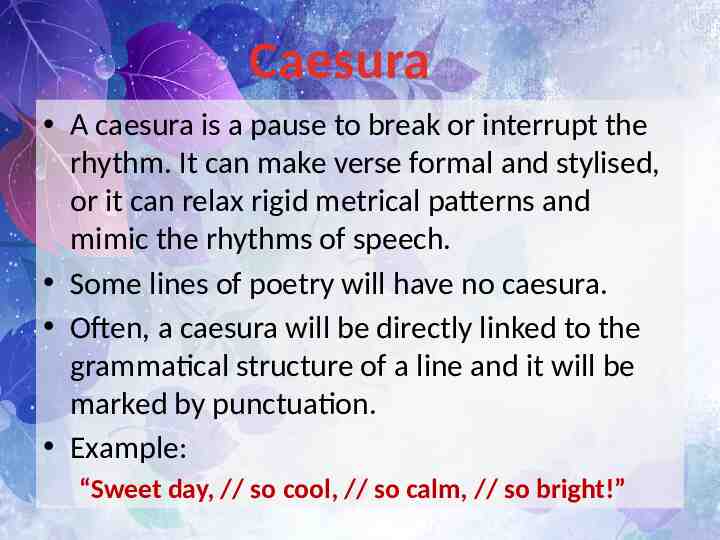

Caesura A caesura is a pause to break or interrupt the rhythm. It can make verse formal and stylised, or it can relax rigid metrical patterns and mimic the rhythms of speech. Some lines of poetry will have no caesura. Often, a caesura will be directly linked to the grammatical structure of a line and it will be marked by punctuation. Example: “Sweet day, // so cool, // so calm, // so bright!”

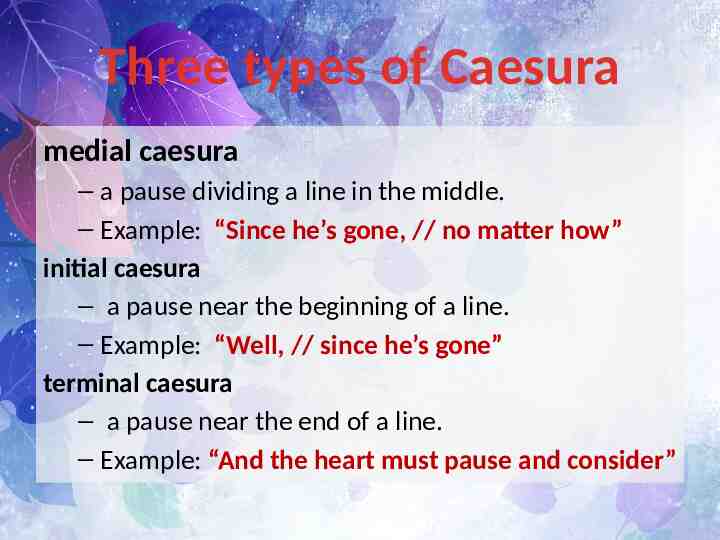

Three types of Caesura medial caesura – a pause dividing a line in the middle. – Example: “Since he’s gone, // no matter how” initial caesura – a pause near the beginning of a line. – Example: “Well, // since he’s gone” terminal caesura – a pause near the end of a line. – Example: “And the heart must pause and consider”

Stressed & d e s s e s r e t l s b n a l U yl S

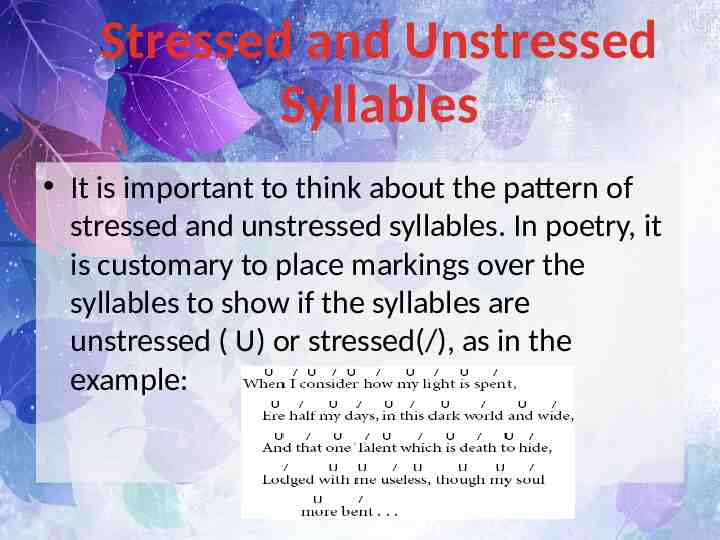

Stressed and Unstressed Syllables It is important to think about the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. In poetry, it is customary to place markings over the syllables to show if the syllables are unstressed ( U) or stressed(/), as in the example:

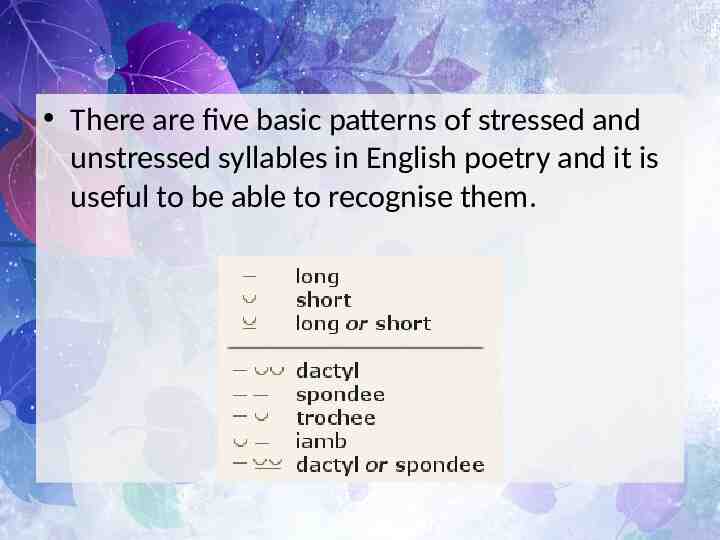

There are five basic patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables in English poetry and it is useful to be able to recognise them.

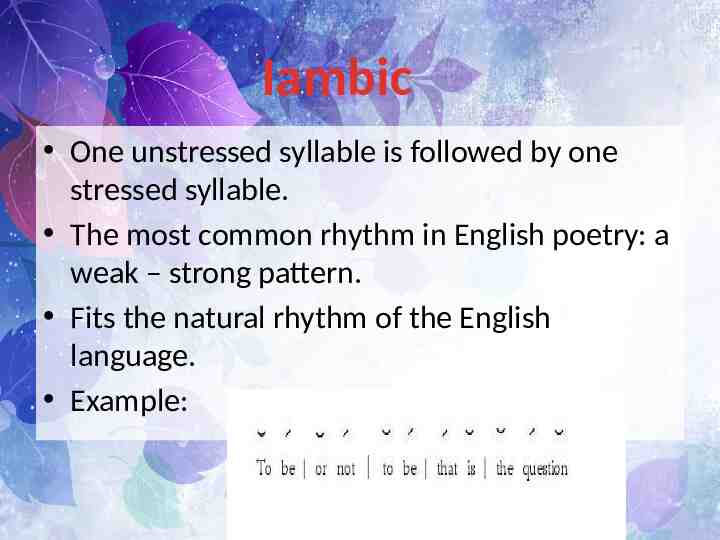

Iambic One unstressed syllable is followed by one stressed syllable. The most common rhythm in English poetry: a weak – strong pattern. Fits the natural rhythm of the English language. Example:

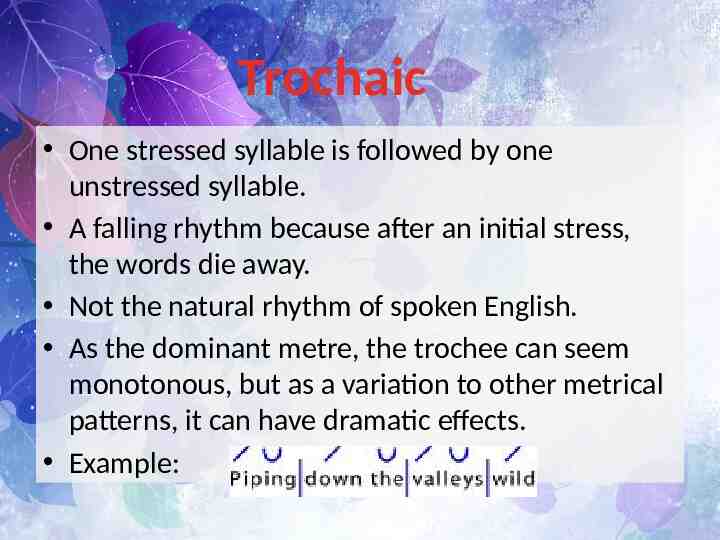

Trochaic One stressed syllable is followed by one unstressed syllable. A falling rhythm because after an initial stress, the words die away. Not the natural rhythm of spoken English. As the dominant metre, the trochee can seem monotonous, but as a variation to other metrical patterns, it can have dramatic effects. Example:

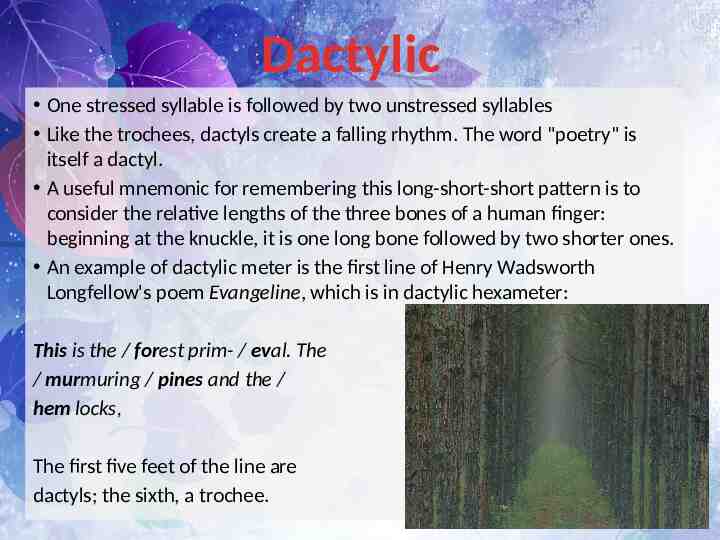

Dactylic One stressed syllable is followed by two unstressed syllables Like the trochees, dactyls create a falling rhythm. The word "poetry" is itself a dactyl. A useful mnemonic for remembering this long-short-short pattern is to consider the relative lengths of the three bones of a human finger: beginning at the knuckle, it is one long bone followed by two shorter ones. An example of dactylic meter is the first line of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem Evangeline, which is in dactylic hexameter: This is the / forest prim- / eval. The / murmuring / pines and the / hem locks, The first five feet of the line are dactyls; the sixth, a trochee.

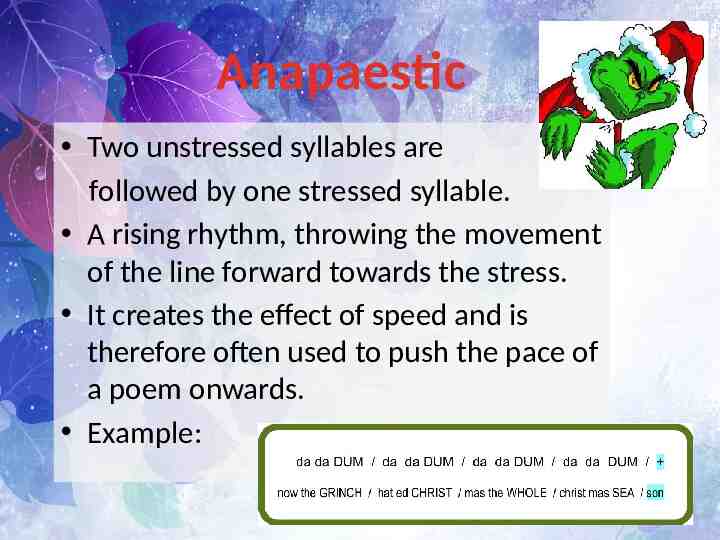

Anapaestic Two unstressed syllables are followed by one stressed syllable. A rising rhythm, throwing the movement of the line forward towards the stress. It creates the effect of speed and is therefore often used to push the pace of a poem onwards. Example:

Spondee Two stressed syllables. Example:

Stanza Analysis Example

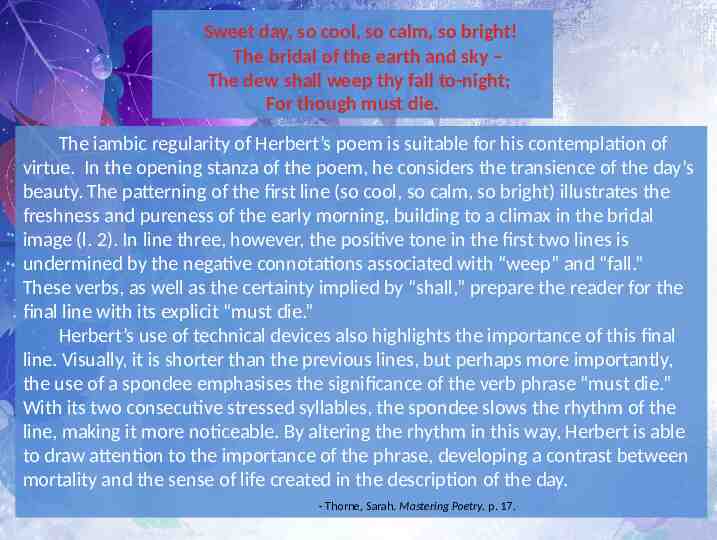

Sweet day, so cool, so calm, so bright! The bridal of the earth and sky – The dew shall weep thy fall to-night; For though must die. The iambic regularity of Herbert’s poem is suitable for his contemplation of virtue. In the opening stanza of the poem, he considers the transience of the day’s beauty. The patterning of the first line (so cool, so calm, so bright) illustrates the freshness and pureness of the early morning, building to a climax in the bridal image (l. 2). In line three, however, the positive tone in the first two lines is undermined by the negative connotations associated with “weep” and “fall.” These verbs, as well as the certainty implied by “shall,” prepare the reader for the final line with its explicit “must die.” Herbert’s use of technical devices also highlights the importance of this final line. Visually, it is shorter than the previous lines, but perhaps more importantly, the use of a spondee emphasises the significance of the verb phrase “must die.” With its two consecutive stressed syllables, the spondee slows the rhythm of the line, making it more noticeable. By altering the rhythm in this way, Herbert is able to draw attention to the importance of the phrase, developing a contrast between mortality and the sense of life created in the description of the day. - Thorne, Sarah. Mastering Poetry. p. 17.