Hospital Acquired Pressure Injury Education Module Presented

23 Slides5.05 MB

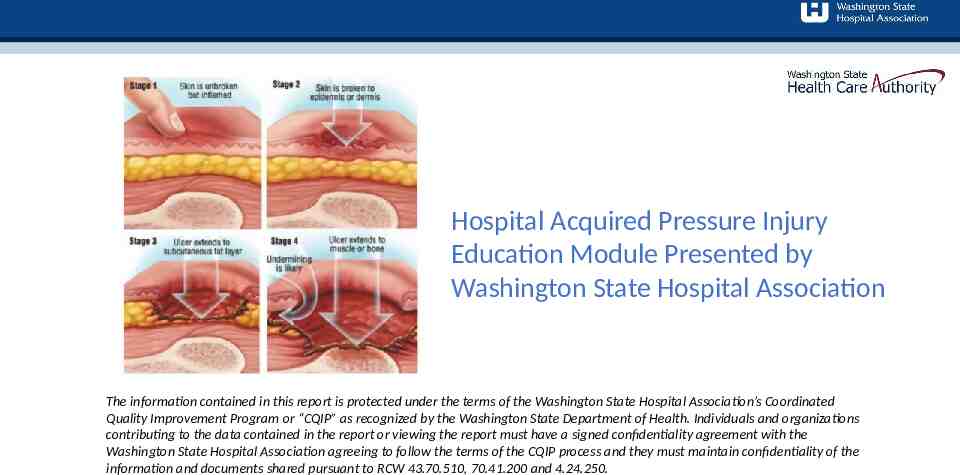

Hospital Acquired Pressure Injury Education Module Presented by Washington State Hospital Association The information contained in this report is protected under the terms of the Washington State Hospital Association’s Coordinated Quality Improvement Program or “CQIP” as recognized by the Washington State Department of Health. Individuals and organizations contributing to the data contained in the report or viewing the report must have a signed confidentiality agreement with the Washington State Hospital Association agreeing to follow the terms of the CQIP process and they must maintain confidentiality of the information and documents shared pursuant to RCW 43.70.510, 70.41.200 and 4.24.250.

Amy Anderson Director Safety and Quality MN, BSN, CNS [email protected] Tina Seery Senior Director Safety and Quality MHA RN CPHQ CPPS LSSBB [email protected]

Objectives: Understand recent data trends Identify vulnerable populations as it relates to pressure injuries Describe the importance of early recognition with a complete skin assessment Recognize devices that may increase patient risk for pressure injuries

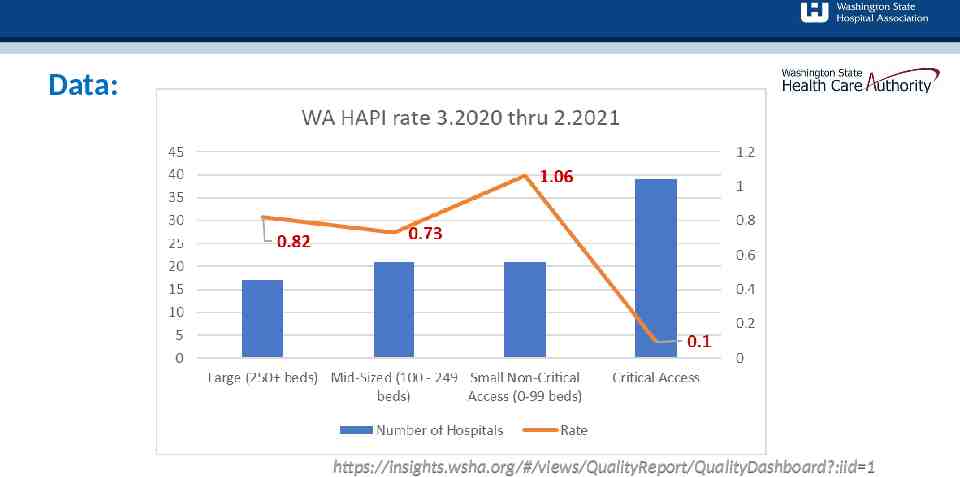

Data: https://insights.wsha.org/#/views/QualityReport/QualityDashboard?:iid 1

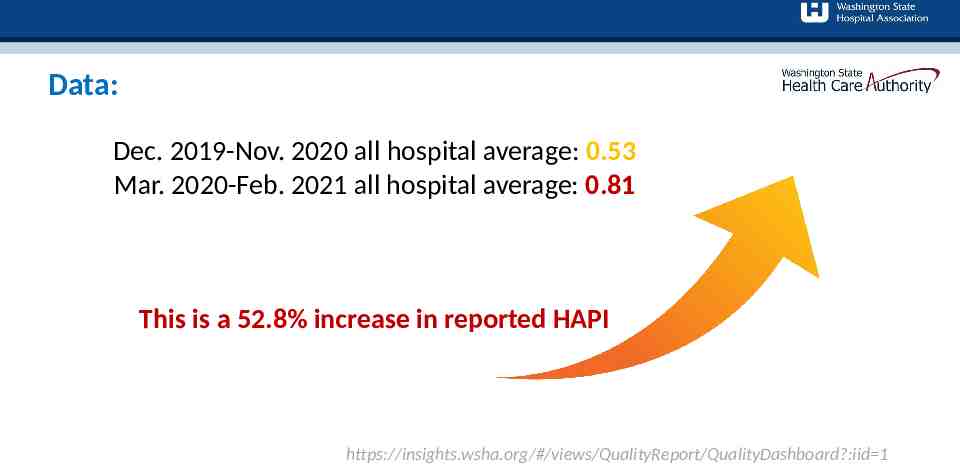

Data: Dec. 2019-Nov. 2020 all hospital average: 0.53 Mar. 2020-Feb. 2021 all hospital average: 0.81 This is a 52.8% increase in reported HAPI https://insights.wsha.org/#/views/QualityReport/QualityDashboard?:iid 1

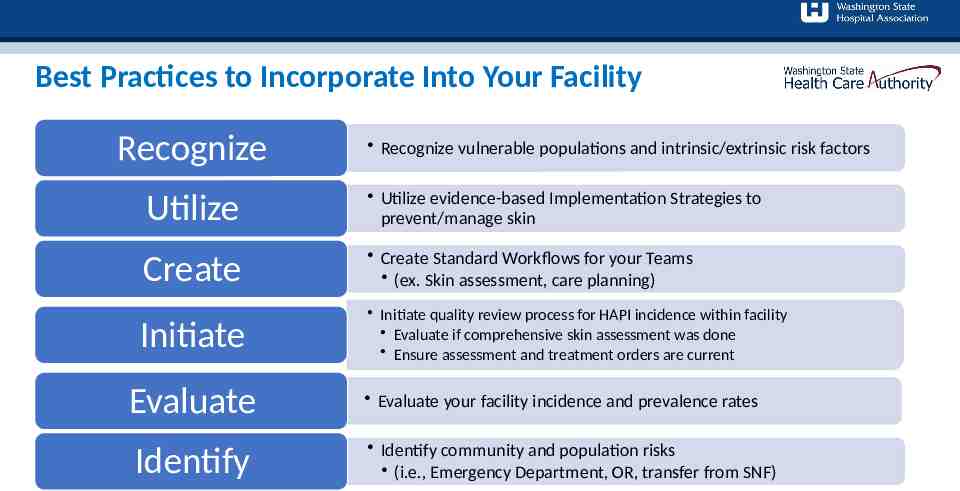

Best Practices to Incorporate Into Your Facility Recognize Recognize vulnerable populations and intrinsic/extrinsic risk factors Utilize Utilize evidence-based Implementation Strategies to prevent/manage skin Create Create Standard Workflows for your Teams (ex. Skin assessment, care planning) Initiate Initiate quality review process for HAPI incidence within facility Evaluate if comprehensive skin assessment was done Ensure assessment and treatment orders are current Evaluate Identify Evaluate your facility incidence and prevalence rates Identify community and population risks (i.e., Emergency Department, OR, transfer from SNF)

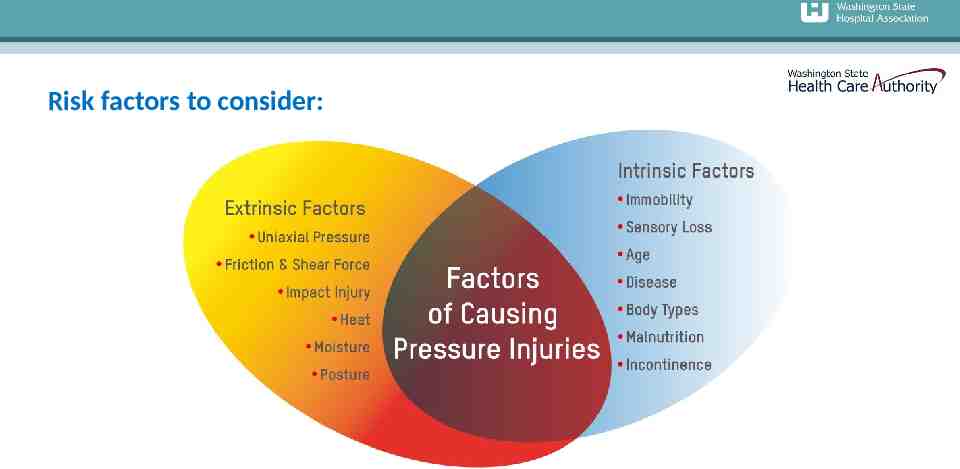

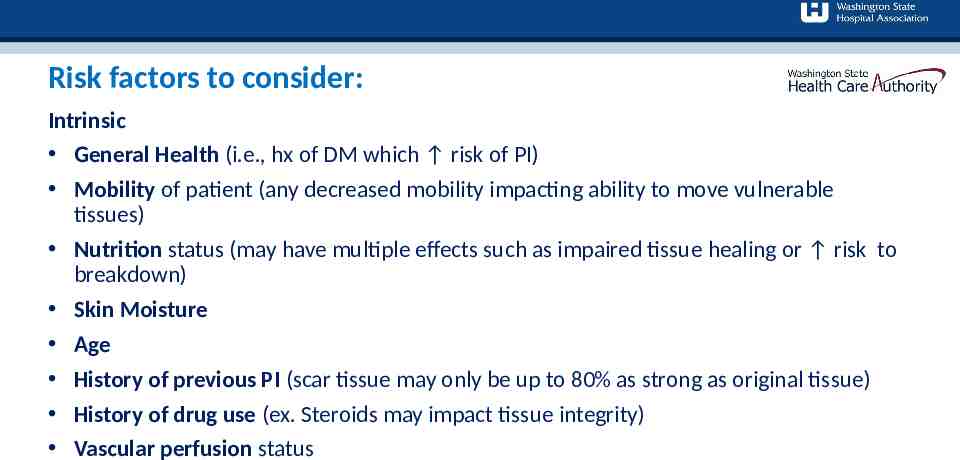

Risk factors to consider:

Risk factors to consider: Intrinsic General Health (i.e., hx of DM which risk of PI) Mobility of patient (any decreased mobility impacting ability to move vulnerable tissues) Nutrition status (may have multiple effects such as impaired tissue healing or risk to breakdown) Skin Moisture Age History of previous PI (scar tissue may only be up to 80% as strong as original tissue) History of drug use (ex. Steroids may impact tissue integrity) Vascular perfusion status

Risk factors to consider: Extrinsic Pressure Force applied perpendicular to tissue Tend to be uniform or circular in shape; neat appearance Shear Action or stress which causes two contiguous internal parts of the body to deform in the transverse plane Tend to cause deeper tissue damage, may not be immediately visible; skin edges may also be ragged Friction Contact force parallel to the skin surface in case of sliding (sliding surfaces along each other) Often presents as a shallow, stripped and painful area; characterized by messy wounds with ragged edges Skin Microclimate Local tissue temperature and moisture at the body/support surface interface Moisture is known to impact the ability of the skin to function

Other vulnerable populations: ANYONE ON SURFACES 2 HOURS (I.E. EMERGENCY ROOM, SURGICAL SERVICES, DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING ) BP BELOW 100/55 HCT BELOW 30 (HGB BELOW 10) SHOCK: SEPTIC, NEUROGENIC, CARDIAC DIALYSIS PROJECTED MULTIPLE SURGERIES SPINAL CORD INJURY/SPINA BIFIDA STROKE OR NEUROLOGICAL DISORDER

Medical Devices Increasing Risk of Pressure Injuries: Medical devices account for more than 30 percent of all hospital-acquired pressure injuries (Health & Education Trust, 2017) Clinicians should assess skin under/around medical devices to identify for early signs of pressure injury Medical devices should be re-positioned frequently in order to redistribute the force and pressure Ensure device is proper size, in proper location and secured properly; additionally, some medical devices may require padding to reduce friction (follow manufacturers guidelines) Documentation and communication: use standardized forms, tools and technologies to assist clinicians in documentation and communication amongst each other

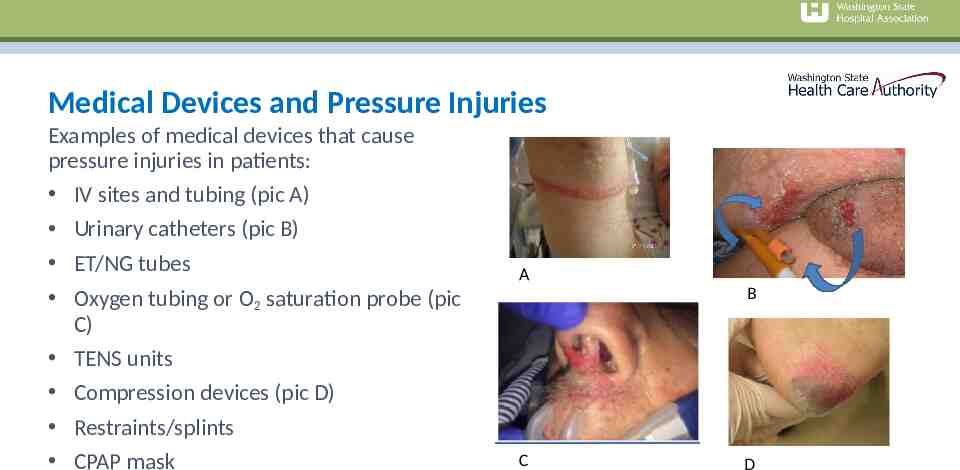

Medical Devices and Pressure Injuries Examples of medical devices that cause pressure injuries in patients: IV sites and tubing (pic A) Urinary catheters (pic B) ET/NG tubes Oxygen tubing or O2 saturation probe (pic C) TENS units Compression devices (pic D) Restraints/splints CPAP mask A B C D

Importance of Early Recognition and Teamwork Prevention requires a coordinated effort among multiple disciplines to develop and implement the patient’s care plan. High quality prevention requires a system culture and operational practices that support teamwork and communication

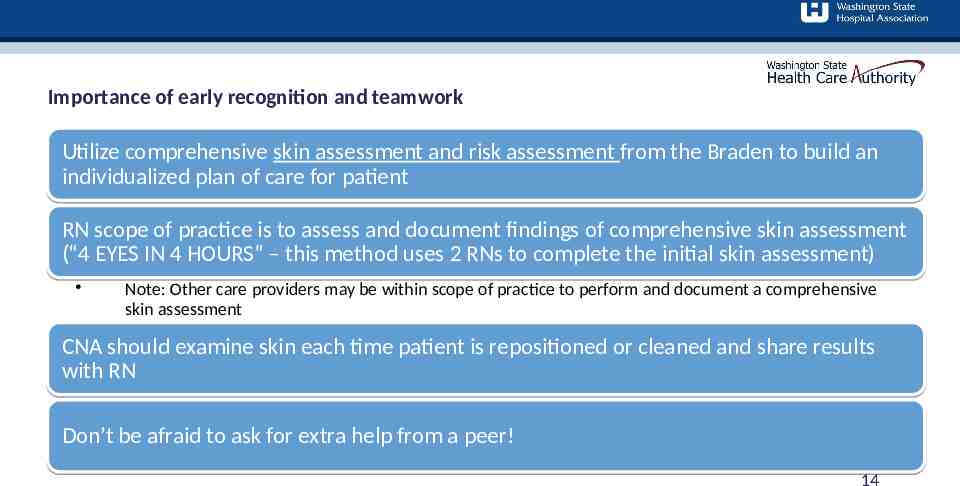

Importance of early recognition and teamwork Utilize comprehensive skin assessment and risk assessment from the Braden to build an individualized plan of care for patient RN scope of practice is to assess and document findings of comprehensive skin assessment (“4 EYES IN 4 HOURS” – this method uses 2 RNs to complete the initial skin assessment) Note: Other care providers may be within scope of practice to perform and document a comprehensive skin assessment CNA should examine skin each time patient is repositioned or cleaned and share results with RN Don’t be afraid to ask for extra help from a peer! 14

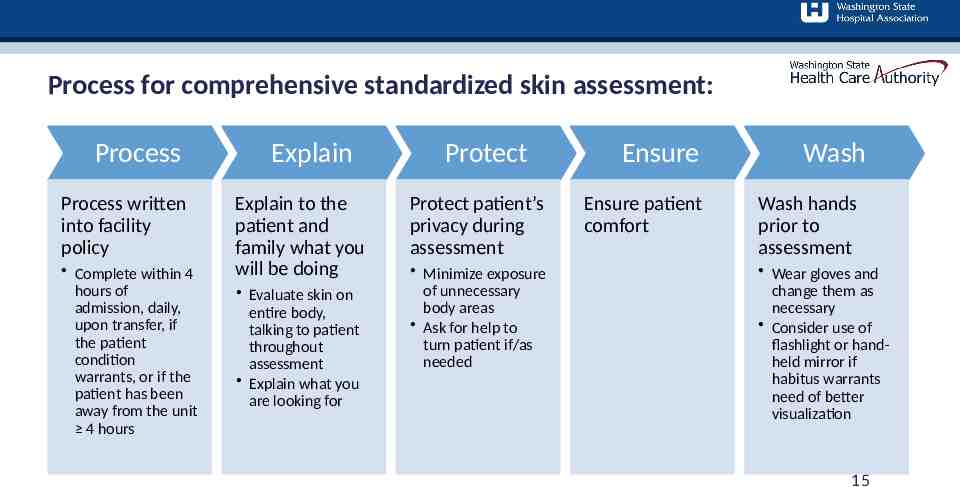

Process for comprehensive standardized skin assessment: Process Process written into facility policy Complete within 4 hours of admission, daily, upon transfer, if the patient condition warrants, or if the patient has been away from the unit 4 hours Explain Explain to the patient and family what you will be doing Evaluate skin on entire body, talking to patient throughout assessment Explain what you are looking for Protect Protect patient’s privacy during assessment Minimize exposure of unnecessary body areas Ask for help to turn patient if/as needed Ensure Ensure patient comfort Wash Wash hands prior to assessment Wear gloves and change them as necessary Consider use of flashlight or handheld mirror if habitus warrants need of better visualization 15

Comprehensive standardized skin assessment: Areas to focus on: Skin under/around medical or compression devices Bony prominences (heels, sacrum, occiput) Areas of decreased sensation or previous skin breakdown (hx of Diabetes Mellitus, Neuropathy, etc.) Patient is receiving medication that decreases sensation (i.e., epidural/spinal) Areas where skin to skin contact is occurring (i.e., penis, back of knees, buttocks, and inner thighs) Areas where skin has not been repositioned in 2 hours (i.e., Emergency Department, EMS transport, Surgical services)

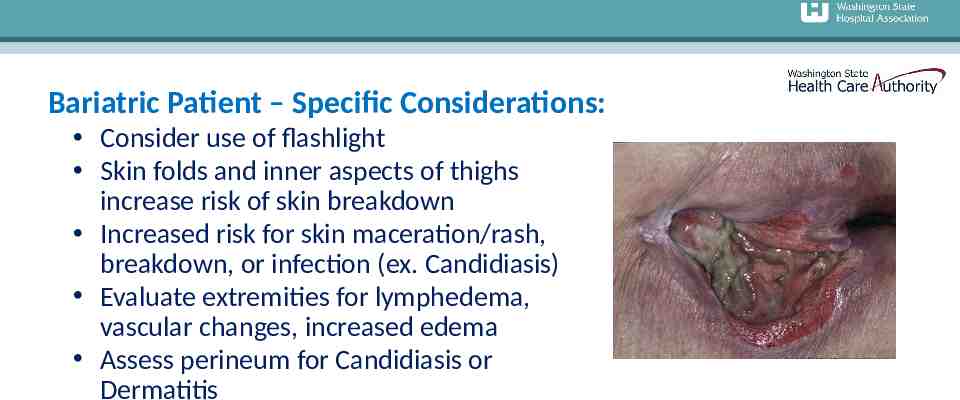

Bariatric Patient – Specific Considerations: Consider use of flashlight Skin folds and inner aspects of thighs increase risk of skin breakdown Increased risk for skin maceration/rash, breakdown, or infection (ex. Candidiasis) Evaluate extremities for lymphedema, vascular changes, increased edema Assess perineum for Candidiasis or Dermatitis

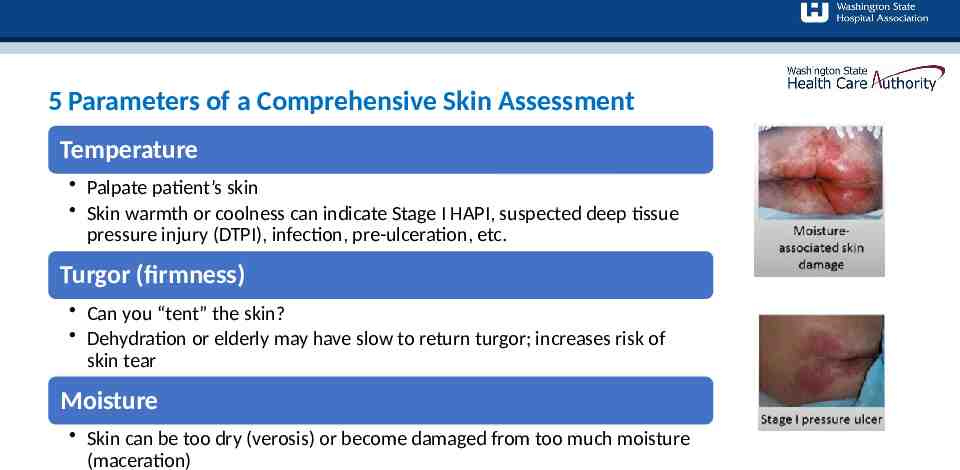

5 Parameters of a Comprehensive Skin Assessment Temperature Palpate patient’s skin Skin warmth or coolness can indicate Stage I HAPI, suspected deep tissue pressure injury (DTPI), infection, pre-ulceration, etc. Turgor (firmness) Can you “tent” the skin? Dehydration or elderly may have slow to return turgor; increases risk of skin tear Moisture Skin can be too dry (verosis) or become damaged from too much moisture (maceration)

5 Parameters of a Comprehensive Skin Assessment Color Redness can indicate rash, infection, cellulitis Sacral redness can be from multiple causes (i.e., incontinence, perspiration, wound exudate, moisture between skin folds, ostomy leak) Ensure correct etiology is found so that appropriate treatment can be initiated Possible vitamin deficiencies causing blotchiness (ex. Vitamin C, Zinc) Investigate blanchable versus non-blanchable erythema, paper-thin skin, purple or reddened skin or any bruises (*darkly pigmented skin does not blanch) Integrity Intact? If not intact, document why it is not intact Possible etiologies to consider are: pressure injury, peripheral vascular (venous/arterial)issues, skin tears/trauma, neuropathic or diabetic. Rashes? Open areas?

Bedside Report: Skin Involv e Report Skin assessment and Braden risk stratification are important elements of bedside handoff Involve patient and family in conversation when possible If skin integrity problems are found, report to LIP as soon as possible 20

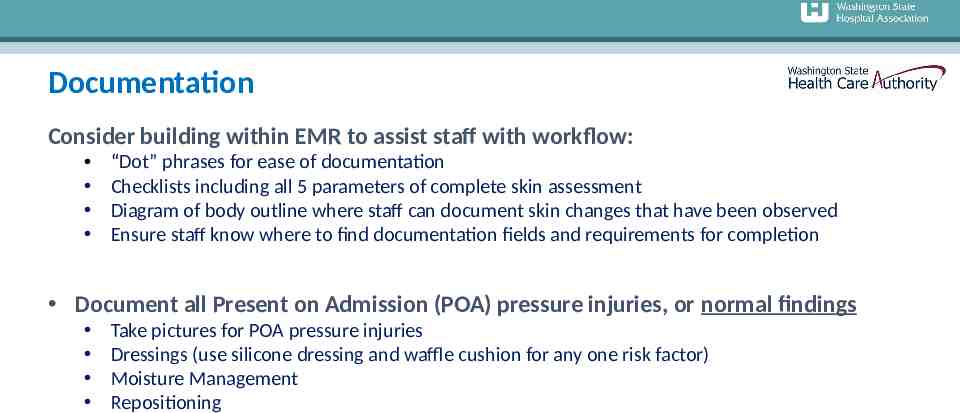

Documentation Consider building within EMR to assist staff with workflow: “Dot” phrases for ease of documentation Checklists including all 5 parameters of complete skin assessment Diagram of body outline where staff can document skin changes that have been observed Ensure staff know where to find documentation fields and requirements for completion Document all Present on Admission (POA) pressure injuries, or normal findings Take pictures for POA pressure injuries Dressings (use silicone dressing and waffle cushion for any one risk factor) Moisture Management Repositioning

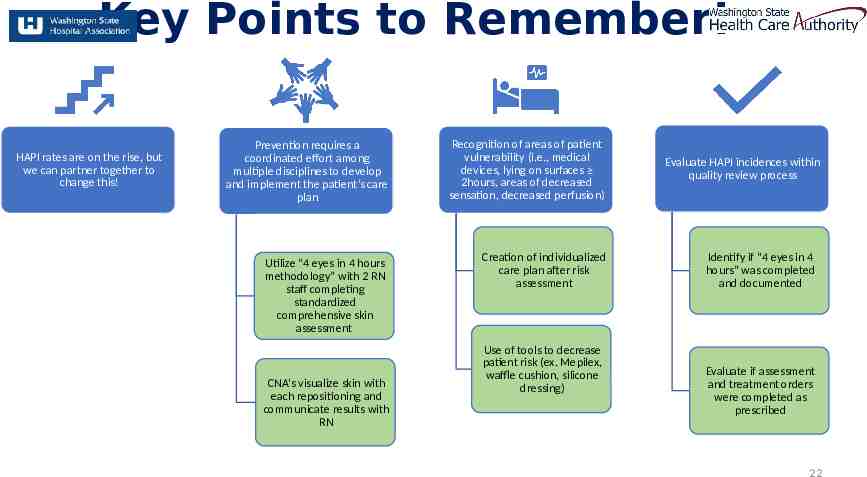

Key Points to Remember! HAPI rates are on the rise, but we can partner together to change this! Prevention requires a coordinated effort among multiple disciplines to develop and implement the patient’s care plan Recognition of areas of patient vulnerability (i.e., medical devices, lying on surfaces 2hours, areas of decreased sensation, decreased perfusion) Utilize “4 eyes in 4 hours methodology” with 2 RN staff completing standardized comprehensive skin assessment Creation of individualized care plan after risk assessment CNA’s visualize skin with each repositioning and communicate results with RN Use of tools to decrease patient risk (ex. Mepilex, waffle cushion, silicone dressing) Evaluate HAPI incidences within quality review process Identify if “4 eyes in 4 hours” was completed and documented Evaluate if assessment and treatment orders were completed as prescribed 22

Referen ces: 1. Health Research & Educational Trust. Hospital Acquired Pressure Ulcers/Injuries (HAPU/I): April 2017. Chicago, IL: Health Research & Educational Trust. 2. https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/settings/hospital/resource/pressureinjury/ workshop/guide3.html 3. https://npiap.com/ 4. https://npiap.com/page/FreeMaterials 5. https://npiap.com/page/2019Guideline 6. Kirkland-Kyhn, Teleten et al. OWM, 2017;63(2):42-47, 2017. 7. Kirkland-Kyhn, Teleten et al. WMP, 2019;65(2):14-19. 8. Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. (2019). Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: clinical practice guideline: the quick reference guideline 2019. 9. Pressure ulcer prevention: pressure, shear, friction and microclimate in context. A consensus 10. Preventing Pressure Ulcers in Hospitals: A Toolkit for Improving Quality of Care. ( ahrq.gov) 11. The Joint Commission. Managing medical device-related pressure injuries. Quick Safety. Issue 43, July 2018. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission 12. World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS). Consensus Document: Role of dressings in pressure ulcer prevention. London, UK: Wounds Int; 2016 23 document. London: Wounds International (2010).