Econ 492: Comparative Financial Crises Lecture 1 12 September 2012

69 Slides334.46 KB

Econ 492: Comparative Financial Crises Lecture 1 12 September 2012 David Longworth This material is copyrighted and is for the sole use of students registered in ECON 492. This material shall not be distributed or disseminated to anyone other than students registered in ECON 492. Failure to abide by these conditions is a breach of copyright, and may also constitute a breach of academic integrity under the University Senate’s Academic Integrity Policy Statement.

Overview I. II. III. IV. Introduction Financial System: Overview Causes of Financial Crises Prediction of Financial Crises Note: AG indicates Franklin Allen and Douglas Gale (2009), Understanding Financial Crises. KA indicates Charles P. Kindleberger and Robert Aliber (2011 or 2005), Manias, Panics, and Crashes. Economics 492 Lecture 1 2

l. Introduction Introductions Economics 492 Lecture 1 3

l. Introduction Introductions August 2007 Economics 492 Lecture 1 4

l. Introduction Introductions August 2007 Outline of Course (handout) Economics 492 Lecture 1 5

l. Introduction Outline of Course (after Fin. Sector Overview) (Prediction) Causes Transmission Prevention Policy Response Economics 492 Lecture 1 6

l. Introduction The paper Presentation and discussion Participation Schedule – Lecture next week – 26 September: your (two paragraph) topic due – 4 October (Thursday): your 2-page outline due – 4 – 24/25 October (and beyond): weekly consultations – 31 October - 21 November: presentations – 28 November: paper due in class and class discussion Economics 492 Lecture 1 7

II. Financial System: Overview Roles played by the financial system Bank balance sheets (assets and liabilities) Risks faced by banks Market failures Economics 492 Lecture 1 8

II. Financial System: Overview Roles played by the financial system – Channelling savings into investment/Efficient allocation over time (consumption/saving, production) (role played by markets, banks, pension funds) – Transferring risk (role played by markets and by banks and insurance companies) – Making markets and providing liquidity (and its various guises and definitions) (role played by markets and by banks) – Maturity transformation (role played by banks) – Effecting payments (role played by banks) Economics 492 Lecture 1 9

II. Financial System: Overview Roles played by the financial system – Channelling savings into investment/Efficient allocation over time Economics 492 Lecture 1 10

II. Financial System: Overview Roles played by the financial system – Transferring Risk Risk sharing – There is always uncertainty about the future, e.g. income – Contingent commodity: “a good whose delivery is contingent on the occurrence of a particular state of nature” (AG) – Two equivalent ways to achieving an efficient allocation of risk » If there are complete markets for contingent commodities (consumers only have to satisfy their budget constraint) » If there are Arrow securities for each state, securities which are a “promise to deliver one unit of money if a given state occurs and nothing otherwise.” (AG) Economics 492 Lecture 1 11

II. Financial System: Overview Roles played by the financial system – Transferring Risk Insurance and pooling risk – When there is a large number of consumers that can be assumed to be independent, the law of large numbers can be used to predict the average outcome – This is what insurance companies do, pooling large numbers of (largely) independent risks, so that the aggregate outcome is approximately constant (each individual could be given a constant level of consumption) Economics 492 Lecture 1 12

II. Financial System: Overview Roles played by the financial system – Making Markets and Providing Liquidity Liquidity definitions – Assets are liquid “if they can easily be converted into consumption without loss of value.” (AG) – Consumers have a preference for liquidity to the extent that they have uncertainty about the timing of their consumption » therefore want to hold liquid assets. Financial institutions (banks) can rely on law of large numbers to provide liquidity to consumers while investing some of their savings in illiquid assets Economics 492 Lecture 1 13

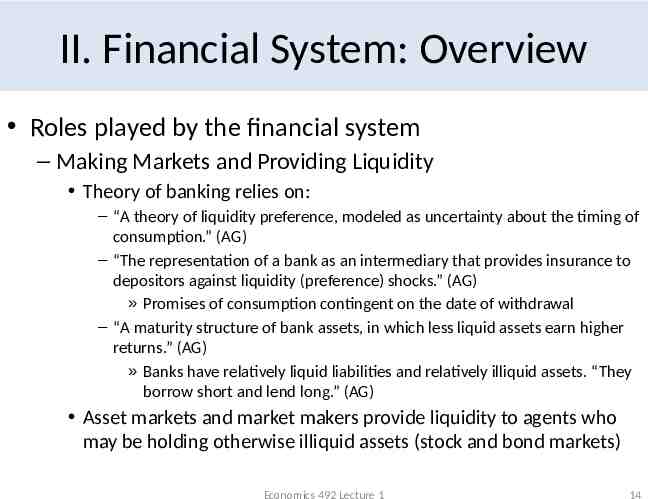

II. Financial System: Overview Roles played by the financial system – Making Markets and Providing Liquidity Theory of banking relies on: – “A theory of liquidity preference, modeled as uncertainty about the timing of consumption.” (AG) – “The representation of a bank as an intermediary that provides insurance to depositors against liquidity (preference) shocks.” (AG) » Promises of consumption contingent on the date of withdrawal – “A maturity structure of bank assets, in which less liquid assets earn higher returns.” (AG) » Banks have relatively liquid liabilities and relatively illiquid assets. “They borrow short and lend long.” (AG) Asset markets and market makers provide liquidity to agents who may be holding otherwise illiquid assets (stock and bond markets) Economics 492 Lecture 1 14

II. Financial System: Overview Roles played by the financial system – Maturity transformation (role played by banks) As we have already seen, banks tend to have shorter-term liabilities than the maturity of their assets – Effecting Payments (role played by banks) This is another reason why consumers place deposits with banks. It is extremely difficult for consumers not to transact with banks because of this. Currency and demand deposits are close to perfect substitutes, but it is difficult to make large payments with currency. Economics 492 Lecture 1 15

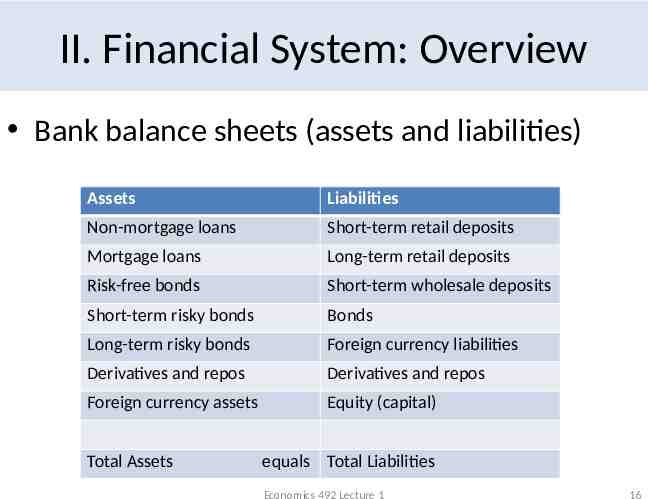

II. Financial System: Overview Bank balance sheets (assets and liabilities) Assets Liabilities Non-mortgage loans Short-term retail deposits Mortgage loans Long-term retail deposits Risk-free bonds Short-term wholesale deposits Short-term risky bonds Bonds Long-term risky bonds Foreign currency liabilities Derivatives and repos Derivatives and repos Foreign currency assets Equity (capital) Total Assets equals Total Liabilities Economics 492 Lecture 1 16

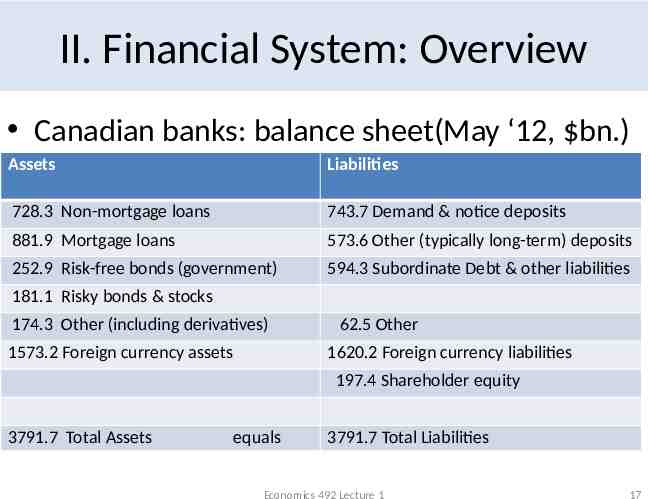

II. Financial System: Overview Canadian banks: balance sheet(May ‘12, bn.) Assets Liabilities 728.3 Non-mortgage loans 743.7 Demand & notice deposits 881.9 Mortgage loans 573.6 Other (typically long-term) deposits 252.9 Risk-free bonds (government) 594.3 Subordinate Debt & other liabilities 181.1 Risky bonds & stocks 174.3 Other (including derivatives) 1573.2 Foreign currency assets 62.5 Other 1620.2 Foreign currency liabilities 197.4 Shareholder equity 3791.7 Total Assets equals 3791.7 Total Liabilities Economics 492 Lecture 1 17

II. Financial System: Overview Risks faced by banks: – credit risk (key to beginning of crises) – funding liquidity risk (key to transmission of crises) – market liquidity risk – market risk – risk to the value of collateral (including housing) – exchange rate risk (if not matched; important in EMEs) Economics 492 Lecture 1 18

II. Financial System: Overview Risks faced by banks: – credit risk (CR): risk of loss due to a debtor’s nonpayment of a loan or a bond or a derivative Applies to everything on asset side of balance sheet except risk-free bonds Economics 492 Lecture 1 19

II. Financial System: Overview Risks faced by banks: – funding liquidity risk (FLR): risk that over a specific horizon a bank will be unable to settle its obligations with immediacy (from Drehmann and Nikolaou, 2009) Applies to risk of not having the ability to raise deposits or bond or equity funding (liability side of balance sheet) or to sell off highly liquid assets (such as risk-free assets) when required to meet obligations Note the obvious connection to bank runs Economics 492 Lecture 1 20

II. Financial System: Overview Risks faced by banks: – market liquidity risk (MLR): risk that the market will not trade an asset (as in a financial crisis), or not trade it near the pre-existing price Banks face this risk on risky bonds and on derivatives There are various measures of asset liquidity – Bid-offer spread: a measure of transactions cost – Market depth: amount that can be transacted at various spreads – Immediacy: time needed to trade a certain amount at a price – Resilience: speed at which prices return to pre-existing levels Economics 492 Lecture 1 21

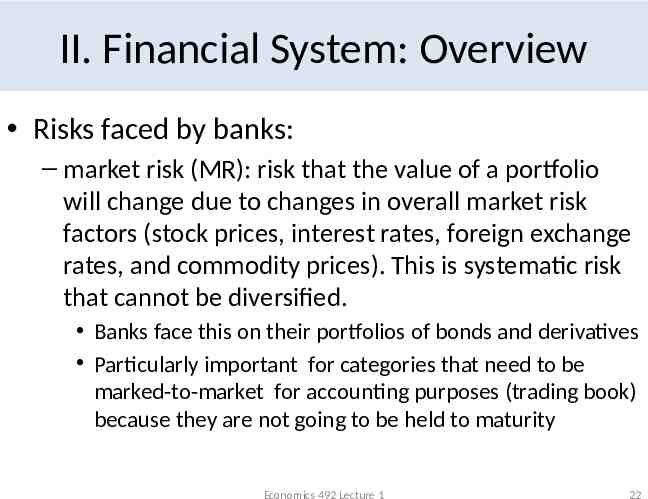

II. Financial System: Overview Risks faced by banks: – market risk (MR): risk that the value of a portfolio will change due to changes in overall market risk factors (stock prices, interest rates, foreign exchange rates, and commodity prices). This is systematic risk that cannot be diversified. Banks face this on their portfolios of bonds and derivatives Particularly important for categories that need to be marked-to-market for accounting purposes (trading book) because they are not going to be held to maturity Economics 492 Lecture 1 22

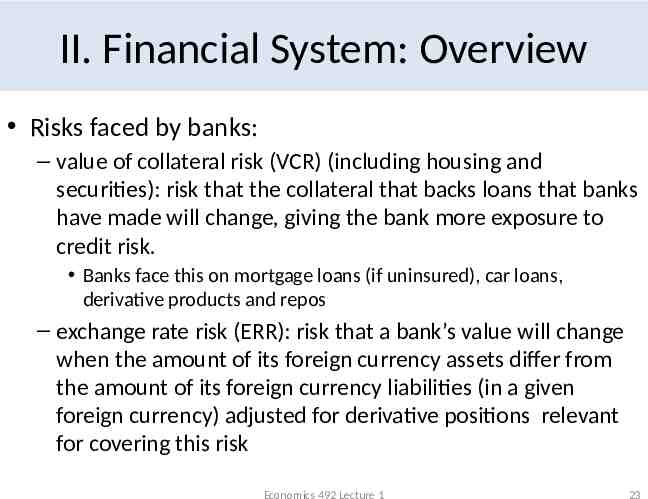

II. Financial System: Overview Risks faced by banks: – value of collateral risk (VCR) (including housing and securities): risk that the collateral that backs loans that banks have made will change, giving the bank more exposure to credit risk. Banks face this on mortgage loans (if uninsured), car loans, derivative products and repos – exchange rate risk (ERR): risk that a bank’s value will change when the amount of its foreign currency assets differ from the amount of its foreign currency liabilities (in a given foreign currency) adjusted for derivative positions relevant for covering this risk Economics 492 Lecture 1 23

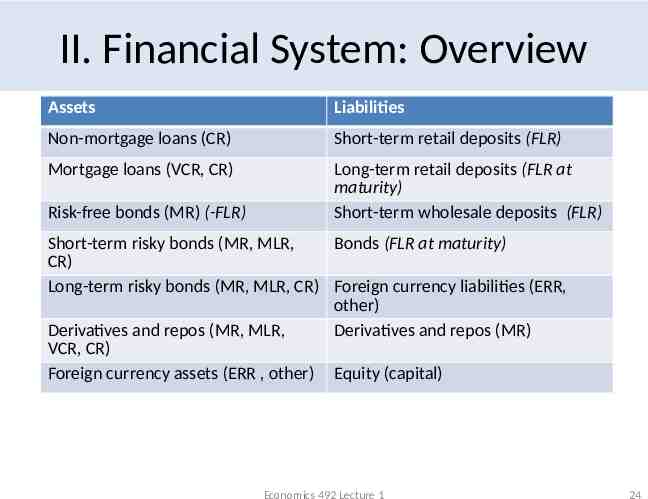

II. Financial System: Overview Assets Liabilities Non-mortgage loans (CR) Short-term retail deposits (FLR) Mortgage loans (VCR, CR) Long-term retail deposits (FLR at maturity) Short-term wholesale deposits (FLR) Risk-free bonds (MR) (-FLR) Short-term risky bonds (MR, MLR, Bonds (FLR at maturity) CR) Long-term risky bonds (MR, MLR, CR) Foreign currency liabilities (ERR, other) Derivatives and repos (MR, MLR, Derivatives and repos (MR) VCR, CR) Foreign currency assets (ERR , other) Equity (capital) Economics 492 Lecture 1 24

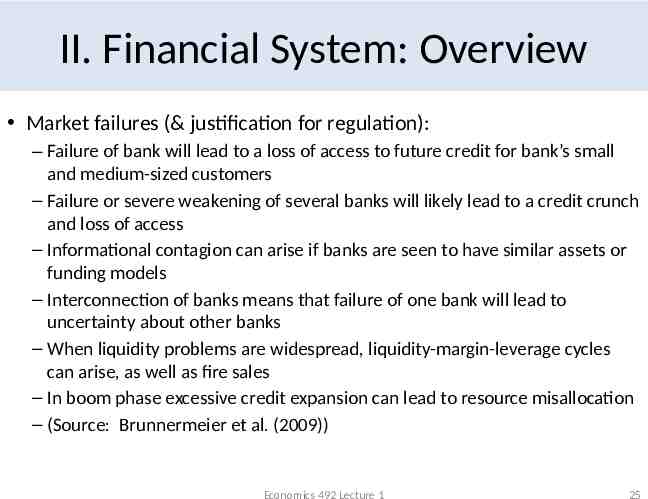

II. Financial System: Overview Market failures (& justification for regulation): – Failure of bank will lead to a loss of access to future credit for bank’s small and medium-sized customers – Failure or severe weakening of several banks will likely lead to a credit crunch and loss of access – Informational contagion can arise if banks are seen to have similar assets or funding models – Interconnection of banks means that failure of one bank will lead to uncertainty about other banks – When liquidity problems are widespread, liquidity-margin-leverage cycles can arise, as well as fire sales – In boom phase excessive credit expansion can lead to resource misallocation – (Source: Brunnermeier et al. (2009)) Economics 492 Lecture 1 25

III. Causes of Crises Types of financial crises: – Banking crisis (financial sector crisis) – Currency crisis Forced depreciation Large devaluation – Sovereign debt crisis Domestic debt External debt Most of lecture time will deal with banking crises Economics 492 Lecture 1 26

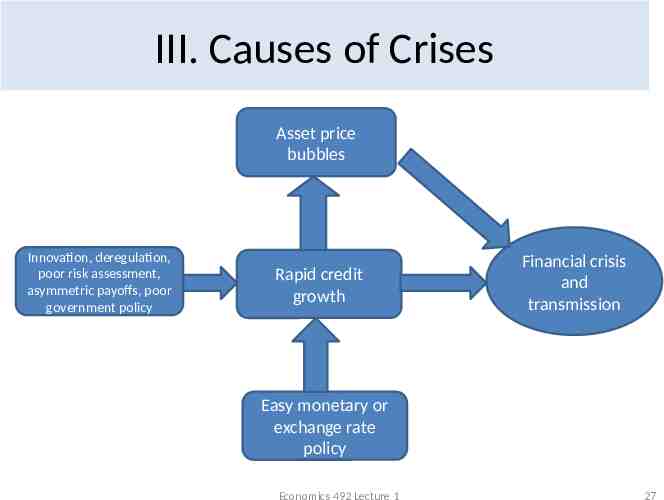

III. Causes of Crises Asset price bubbles Innovation, deregulation, poor risk assessment, asymmetric payoffs, poor government policy Rapid credit growth Financial crisis and transmission Easy monetary or exchange rate policy Economics 492 Lecture 1 27

III. Causes of Crises Rapid growth in credit (aggregate or sector specific) seems to be present in almost all financial crises, especially the ones associated with banking crises or asset price bubbles – Kindleberger and Aliber: “For historians each event is unique. In contrast economists maintain that there are patterns in the data and particular events are likely to introduce similar responses. History is particular; economics is general.” Economics 492 Lecture 1 28

III. Causes of Crises Minsky focused on procyclical changes in the supply of credit – In the expansion, investors gain optimism, raise estimates of profitability of investments, borrow more Lenders also gain optimism, lowering risk assessments and becoming less risk averse, and lend more – In the contraction, investors lose their optimism, lower estimates of profitability, borrow less Lenders have increased loan losses and become more cautious, lending less Economics 492 Lecture 1 29

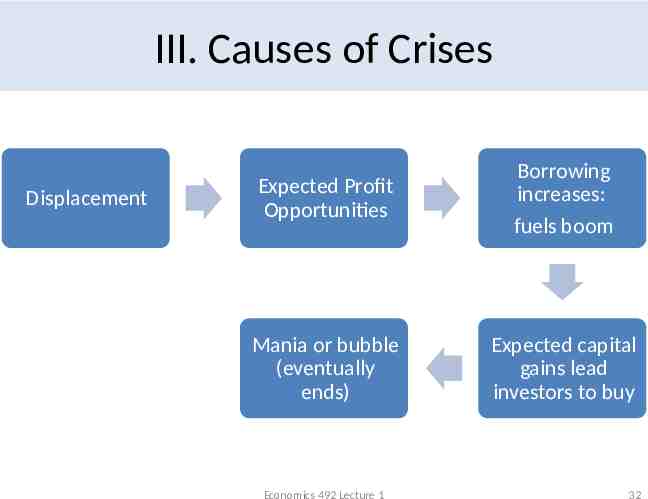

III. Causes of Crises Minsky believed that the procyclical changes in the supply of credit led to financial fragility and an increased probability of a crisis (KA, Ch. 3) – Cycle started by a displacement: an exogenous outside shock – This displacement leads people to believe there are improved profit opportunities in at least one important sector of the economy. Borrowing rises. – This expansion of credit fuels the boom Economics 492 Lecture 1 30

III. Causes of Crises Minsky – Euphoria might develop: investors buy in expectation of capital gains Loan losses incurred by the lenders decline and they respond and become more optimistic and reduce the minimum downpayments and the minimum margin requirements There can be a move away from normal rational behaviour to manias or bubbles Economics 492 Lecture 1 31

III. Causes of Crises Displacement Expected Profit Opportunities Borrowing increases: fuels boom Mania or bubble (eventually ends) Expected capital gains lead investors to buy Economics 492 Lecture 1 32

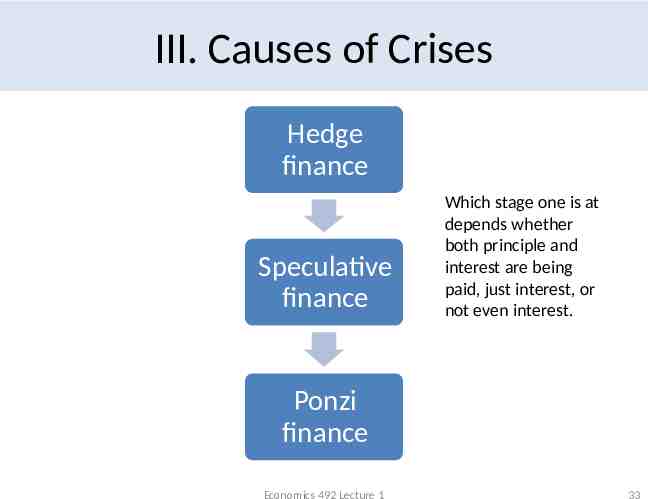

III. Causes of Crises Hedge finance Speculative finance Which stage one is at depends whether both principle and interest are being paid, just interest, or not even interest. Ponzi finance Economics 492 Lecture 1 33

III. Causes of Crises The rapid growth in credit (aggregate or sector specific) can arise from a number of factors: – Financial deregulation/liberalization (KA, Reinhart) Ex.: Led to bubbles in real estate and stocks in Nordic countries – – – – Japanese banking regulators had eased restrictions on Japanese banks abroad Nordic banking regulators had eased restrictions on banks borrowing abroad Loans to Nordic borrowers fueled the bubbles Banks failed – Financial innovation Examples in the most recent crisis – – – – – Sub-prime loans Adjustable rate mortgages in the United States (with teaser rates) Asset-backed Commercial Paper (with unspecified assets backing it) in Canada CDOs: collateralized debt obligations SIVs Economics 492 Lecture 1 34

III. Causes of Crises The rapid growth in credit can arise from: – Poor assessment of risk (risk management, black swans) Value-at-risk calculations were based on short historical periods that did not include “stressed periods” of abnormally high volatility These and other calculations were often based on the “normal” statistical distribution, but the empirical distributions were often fat-tailed Black-swan phenomena: because they haven’t been seen (like black swans, which were native only to Australia), they will never be seen Correlations tend towards one in crises, so the benefits from diversification tend to disappear then Generally, an overemphasis on statistical models (sometimes, overly simple ones), with not enough emphasis on thinking about what could go wrong with a given portfolio, especially where there had been financial innovations – Movements in interest-rate spreads (over governments) on new products don’t say much Overemphasis on rationality of markets Economics 492 Lecture 1 35

III. Causes of Crises The rapid growth in credit can arise from: – Too big to fail Managers and shareholders believe that their bank is too-big-to-fail and that they will be bailed out by the government if they are in danger of failing. Therefore they take more risks. Bondholders and large depositors believe that they will be bailed out by the government and are therefore willing to lend more to banks at narrow spreads over risk-free rates even when the banks are expanding credit rapidly Economics 492 Lecture 1 36

III. Causes of Crises The rapid growth in credit can arise from: – Compensation schemes for management and traders that are asymmetric and not risk-adjusted – Compensation is based on business volume and current profits, even when investments are longer-term. – CEOs and traders may have left (or may leave) when the chickens come home to roost. Economics 492 Lecture 1 37

III. Causes of Crises The rapid growth in credit can arise from: – Inappropriate government policy regarding sectoral credit expansion e.g., encouraging loans to those who are unable to pay them – Example, U.S. sub-prime Economics 492 Lecture 1 38

III. Causes of Crises The rapid growth in credit (aggregate or sector specific) can also arise from easy monetary policy or inappropriate exchange rate policy (especially fixed exchange rates) – Argument that U.S. monetary policy was too easy from 2003-07 Too focused on dangers of deflation and too little focused on special factors keeping down inflation Economics 492 Lecture 1 39

III. Causes of Crises Note: rapid growth in credit raises leverage, which is the ratio of assets to capital (net worth) Leverage is closely related to the following debt ratios: – (for households): debt / personal dispos. income – (for businesses): debt / equity – (for governments): debt / GDP Economics 492 Lecture 1 40

III. Causes of Crises The Austrian school (e.g., Hayek) puts emphasis on the excess capital that is created during the credit boom. This inhibits investment during the recovery period. Economics 492 Lecture 1 41

III. Causes of Crises Credit expansion places the emphasis on credit decisions gone bad and the eventual insolvency (failure)of banks. When we talk about transmission, we will see that we can’t entirely divorce insolvency from illiquidity. – Banks can become illiquid even if they are solvent – In turn, their illiquidity can lead to their insolvency – Suspicion about solvency, however, is the greatest cause of illiquidity Economics 492 Lecture 1 42

III. Causes of Crises Asset bubbles are typically a contributing factor to crises. They typically are supported by rapid sectoral credit expansion. – When asset bubbles are not associated with rapid credit expansion, there is typically less of a problem when they burst because the financial sector is less harmed (banks don’t typically fail in such circumstances). Example: Tech bubble in late 1990s – Asset bubbles most common in housing or real estate, and in stock markets (but also exchange markets, commodities) – Shiller has been a proponent of a psychological effect in the development of bubbles (rejects efficient markets) Economics 492 Lecture 1 43

III. Causes of Crises 7 biggest financial bubbles in last 40 years (KA) – Bank loans to Mexico and other developing countries in the 1970s – Japanese bubble in real estate and stocks in late 1980s – Nordic bubble in real estate and stocks in late 1980s (Finland, Norway, Sweden) – Asian crisis following bubble in real estate and stocks in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and others – Capital flows into Mexico in 1990-93 – Tech stock bubble in U.S. from 1995-2000 – Bubbles in real estate in U.S., U.K., Ireland, Iceland, Spain and Hungary in early 2000s and the world financial crisis 2007-2009(2012) Economics 492 Lecture 1 44

III. Causes of Crises “Quantitative antecedents of financial crises” from Carmen Reinhart (NBER, March 2012): – Capital inflows – Equity prices – Housing Prices – Inverted V real output growth – Rise in indebtedness (private or public sector) Economics 492 Lecture 1 45

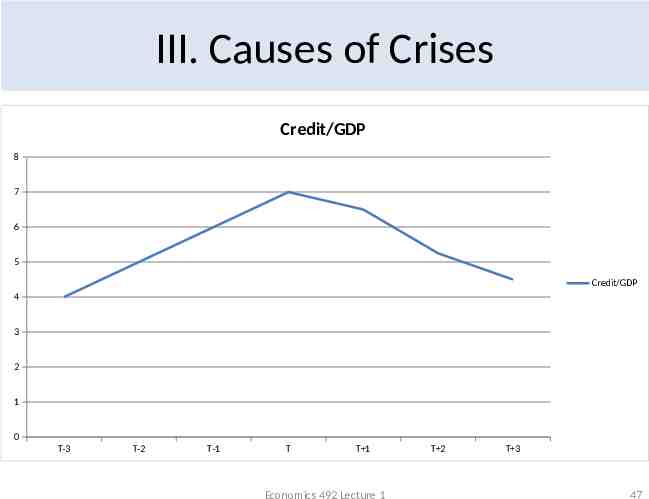

III. Causes of Crises For those who will not be using statistical methods, “Event Study Graphs” (e.g., IMF GFSR, September, 2011, Chapter 3, p.11) can be helpful – Plot key indicators (e.g., credit/GDP, real asset prices) from T-k through T (onset of crisis) to T k – Could average a number of crisis countries (actual dates of T could differ across countries) – Could compare to an average of paired non-crisis countries Economics 492 Lecture 1 46

III. Causes of Crises Credit/GDP 8 7 6 5 Credit/GDP 4 3 2 1 0 T-3 T-2 T-1 T T 1 Economics 492 Lecture 1 T 2 T 3 47

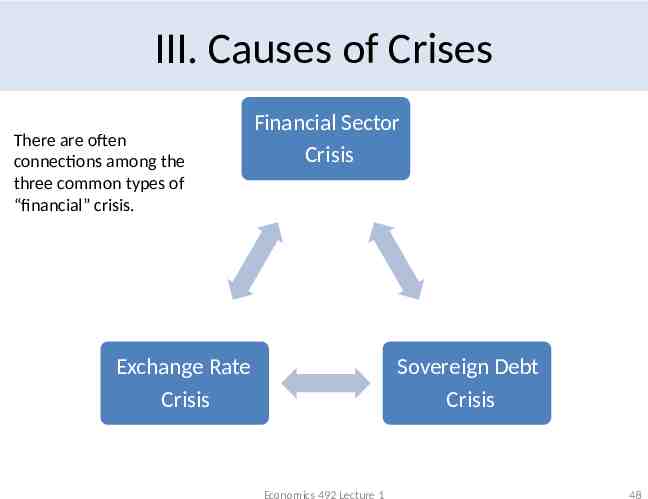

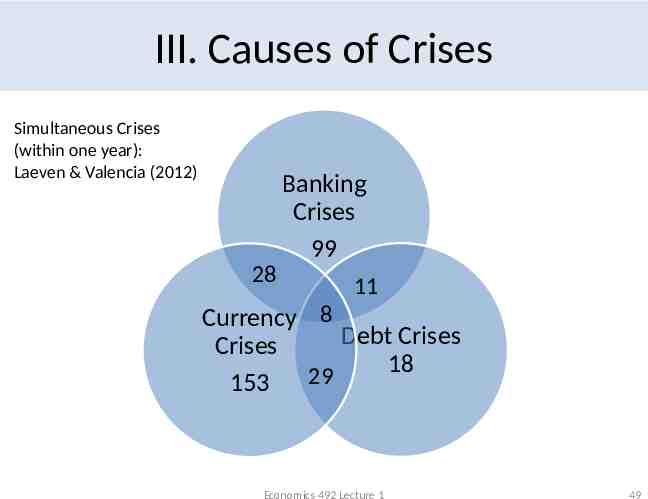

III. Causes of Crises There are often connections among the three common types of “financial” crisis. Financial Sector Crisis Exchange Rate Crisis Sovereign Debt Crisis Economics 492 Lecture 1 48

III. Causes of Crises Simultaneous Crises (within one year): Laeven & Valencia (2012) Banking Crises 99 28 11 Currency 8 Debt Crises Crises 18 29 153 Economics 492 Lecture 1 49

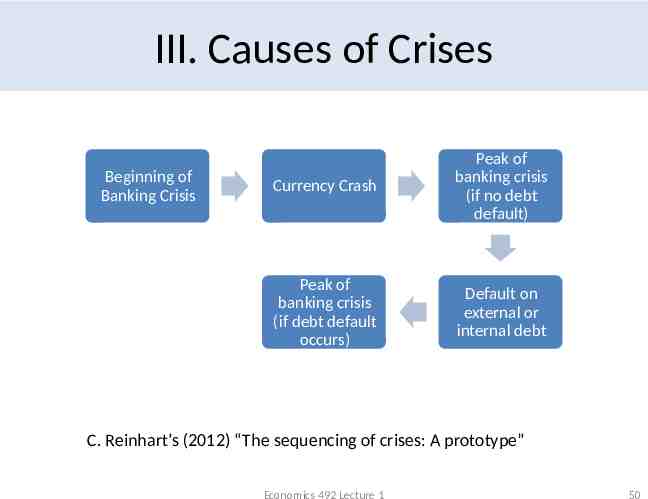

III. Causes of Crises Beginning of Banking Crisis Currency Crash Peak of banking crisis (if no debt default) Peak of banking crisis (if debt default occurs) Default on external or internal debt C. Reinhart’s (2012) “The sequencing of crises: A prototype” Economics 492 Lecture 1 50

III. Causes of Crises Sequencing of Crises (Laeven & Valencia,2012) – 16% of banking crises preceded by currency crisis (within 3 years) – 21% of banking crises precede a currency crisis – 1% of banking crises preceded by sovereign debt crisis – 5% of banking crises precede a sovereign debt crisis Economics 492 Lecture 1 51

III. Causes of Crises Some suggested areas for papers What was the relationship between credit growth (aggregate or sectoral) and various episodes of asset price bubbles? (In recent crisis, could compare across US, UK, Spain, Ireland, Iceland, Hungary) What has been the relationship between capital flows and various episodes of asset price bubbles (especially in EME stock markets or housing markets)? What has been the relationship between the sovereign debt crises in Greece, Ireland, and Portugal (and feared crises in Spain and Italy) and other types of “financial crises” in the same countries? Economics 492 Lecture 1 52

III. Causes of Crises Some suggested areas for papers Were financial crises worse in countries where the capital stock grew more rapidly? Put another way, which of the following predict the severity of a crisis: credit, asset price bubbles, capital stock growth? Focusing on those crises where there was a real estate bubble, which of the following predict the severity of a crisis: mortgage credit, total credit, real house prices, housing stock growth? What are the similarities of the countries in crisis in the Euro area and how do these compare to the countries not in crisis in that area? (Event study graphs—what are the interesting indicators?) Economics 492 Lecture 1 53

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises In the literature, there are two main types of approaches to prediction – One deals with Type I and Type 2 errors, and minimization of noise-to-signal ratio A related approach has decision trees – Second deals with estimation of multivariate logit (or probit) models (with maximum likelihood methods) Economics 492 Lecture 1 54

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises Type I and Type II errors and noise-to-signal ratio – Type I error is a false positive (no crisis predicted when was a crisis) The significance level α of a test – Type II error is a false negative (crisis occurred when none was predicted) β, or 1 minus the power of the test Economics 492 Lecture 1 55

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises Type I and Type II errors and noise-to-signal ratio – Noise-to-signal ratio: ratio of Number of predictions of crisis when no crisis / number of observations of no crisis, to Number of predictions of crisis when crisis / number of observations of a crisis – Typically choose rule minimizing noise-to-signal ratio in this literature Economics 492 Lecture 1 56

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises Type I, Type II errors and noise-to-signal ratio – Some papers report unconditional probability of a crisis (c/nT) where c is number of crises, n is number of countries, and T is number of years These papers then go on to report conditional probabilities of a crisis given the condition A A* for some indicator variable A (say, credit growth or level) Also, can have a more complicated formulation such as the conditional probability: – P(Crisis A A*, B B*, C C*) Economics 492 Lecture 1 57

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises Type I, Type II errors and noise-to-signal ratio – Note sufficient condition P (Crisis A A’) 1 – Note necessary condition P (A A ’’ Crisis) 1 – Then want to constrain grid search to A’’ A* A’ – Note can do in-sample, out-of-sample exercise Example, estimate before recent crisis, see how well it predicts which countries experienced recent crisis Economics 492 Lecture 1 58

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises Type I and Type II errors and noise-to-signal ratio – Three key articles on prediction of banking crises are Borio and Lowe (2002 BIS WP) and Borio and Drehmann (2009 BIS WP 284, 2009 March BIS Quarterly Review) – Important inputs into their work were the dating of financial crises by Bordo et al. (2001 Appendix A) and work by Kaminsky and Reinhart on twin crises (1999 AER)(important in its own right) – Authors use gaps between levels of variables and trends for those variables, using recursive Hodrick-Prescott procedure Procedure minimizes weighted average of sum of squared deviations of actual from trend and sum of squared second differences of trend Economics 492 Lecture 1 59

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises Type I, Type II errors and noise-to-signal ratio – The main result from the Borio-Drehmann piece is that, when credit-to-GDP ratios relative to trend and real property prices relative to trend and/or real stock prices relative to trend are quite high, the probability of a banking crisis is quite elevated. Economics 492 Lecture 1 60

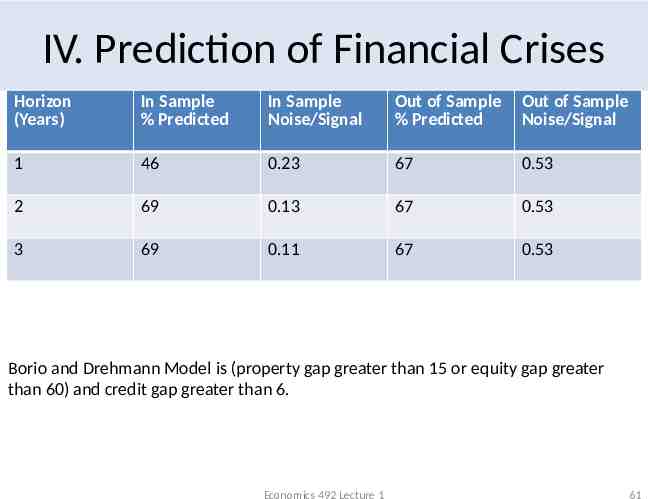

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises Horizon (Years) In Sample % Predicted In Sample Noise/Signal Out of Sample % Predicted Out of Sample Noise/Signal 1 46 0.23 67 0.53 2 69 0.13 67 0.53 3 69 0.11 67 0.53 Borio and Drehmann Model is (property gap greater than 15 or equity gap greater than 60) and credit gap greater than 6. Economics 492 Lecture 1 61

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises Logit (or probit) model – Logit model is based on logistic function: ) Where Note, as (no crisis) Note , as (crisis) If larger values of x are associated with a greater chance of crisis then their coefficients will be positive. Economics 492 Lecture 1 62

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises Logit (or probit) model – Probit model is based on the inverse cumulative density function of the standard normal distribution – (Many feel that practically the differences between probit and logit are not too large. Estimates of multivariate logit tend to converge better/faster than estimates of multivariate probit.) Economics 492 Lecture 1 63

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises Logit Regressions – Schularick and Taylor (2009 NBER) show that it is real loan growth, not real money growth, than predicts banking crises historically – Reinhart-Rogoff (2011 AER) show that This time is Not different in many different dimensions. Systemic banking crises in financial centers (U.S., U.K., and historically France) help explain domestic banking crises External-debt-to-GDP ratio helps explain banking crises Domestic banking crises help explain sovereign debt defaults Growth in public debt helps explain sovereign debt defaults Economics 492 Lecture 1 64

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises Logit Regressions – Gourinchas & Obstfeld (2012, AEJMacro) show Domestic credit growth and real currency appreciation are best predictors of crises in general (advanced countries and EMEs) Higher level of foreign exchange reserves reduces probability of crises Public indebtedness can raise probability of banking (and currency) crises in EMEs – Eichengreen (2004, Ch.5) estimates regressions for various exchange rate “events”, including “crises” Economics 492 Lecture 1 65

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises Probit Regressions – IMF (GFSR, Sep. 2011) shows that higher credit-toGDP gap or credit-to-GDP growth will increase probability of systemic banking crisis Probabilities increase further when lagged increase in equity prices is higher Economics 492 Lecture 1 66

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises Some suggested areas for papers: – Add to Borio and Drehmann an international dimension: contagion from other crises or assets of domestic banks in foreign countries or – In Reinhart and Rogoff (2011) explore whether the inclusion of both external debt ratio and growth in overall public debt changes conclusions about what predicts banking crises and defaults post 1974 – Using estimated equations from various authors, what are the probabilities of sovereign defaults by Spain and Italy and other countries with high or rising debt at present? Economics 492 Lecture 1 67

IV. Prediction of Financial Crises Some suggested areas for papers: – What predicts the spread in long-term rates between the periphery countries in the euro area and Germany? (events and longer-term factors) – To what extent does net government debt add information to gross government debt in predicting sovereign debt crises? – Add real house price gaps and real equity price gaps to specifications of Gourinchas and Obstfeld Economics 492 Lecture 1 68

Suggestions for this week Review Lecture at ECON 492 web site Skim through Reference List for ECON 492 on ECON 492 web site; what sparks your interest? Pursue a reference. Read one or two of: – KA chapters 1-3 (skim the rest) – Reinhart and Rogoff chapters 1, 10, 13 (skim the rest) – Gourinchas & Obstfeld (2012, AEJMacro) “Stories of the 20th Century for the 21st” – Reinhart and Rogoff (2011, AER), “From Financial Crash to Debt Crisis” – The Squam Lake Report chapter 1 If you have an idea of what you would like to do already, see me today or tomorrow, or e-mail me Economics 492 Lecture 1 69