Depression in Medical Settings APM Resident Education

52 Slides429.47 KB

Depression in Medical Settings APM Resident Education Curriculum Revised 2019: Christopher Wilson, DO, Iqbal Ahmed, MD Revised 2013: Sermsak Lolak, MD Revised 2011: Robert C. Joseph, MD, MS Original version: Pamela Diefenbach, MD, FAPM, Lead Psychiatrist, Mental Health Integration in Primary Care, Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Clinical Professor of Psychiatry & Biobehavioral Sciences, UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine & UCLA Semel Institute of Neuroscience Version of March 15, 2019 ACADEMY OF CONSULTATION-LIAISON PSYCHIATRY Psychiatrists Providing Collaborative Care Bridging Physical and Mental Health

Learning Objectives By the end of the lecture, the viewer will be able to: 1. Describe the types and characteristics of depression in a variety of medical settings 2. Appreciate the diverse medical conditions, medication therapies and psychiatric conditions that contribute to depressive symptoms 3. List the evidence-based therapies for depression in the medically ill Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Overview Classification of depression Prevalence in medical Settings Evaluation Time course and associations Treatment Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Depressive Disorders (DSM-5) Major Depressive Disorder Persistent Depressive Disorder (Dysthymia) Adjustment disorder With depressed mood Depressive Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition Substance/Medication-Induced Depressive Disorder Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Some Medical Conditions Closely Associated with Depressive Symptoms Stroke Parkinson’s disease Multiple sclerosis Epilepsy Huntington’s disease Pancreatic and lung cancer Diabetes Heart disease Hypothyroidism Hepatitis C HIV/AIDS Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Difficulties in Diagnosing Depression in the Medically Ill Medical symptoms can overlap with depressive symptoms – Fatigue – Anorexia and/or weight loss – Poor concentration – Anhedonia and or apathy Difficult to make the attribution to either the psychological or medical conditions Medications and interactions can contribute to depressive symptoms Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Depression Criteria Controversy Exclusive criteria Substitutive criteria Inclusive criteria Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry (Bukberg, et. al, 1984)

Exclusive Criteria Exclusive proponents: The clinician excludes those criteria they can directly attribute to the medical condition – Difficult to weigh and decide – Identifies the most severe forms of depression – May miss milder forms of depression & thus missing opportunities to intervene Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Substitutive Criteria More weight is given to the psychological symptoms of depression, not the somatic symptoms of depression – Substitution of symptoms such as irritability, tearfulness, social withdrawal Unclear which symptoms to include or exclude Excludes some somatic symptoms – May miss severe forms of depression Approach not widely adopted Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Inclusive Criteria Inclusive approach: all symptoms are included without any weight to medical condition Shown to be the most sensitive and reliable approach Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Depression in medical illness Coexistence Induced by illness or medications Causes or exacerbates somatic symptoms Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Prevalence in Medical Settings ACADEMY OF CONSULTATION-LIAISON PSYCHIATRY Psychiatrists Providing Collaborative Care Bridging Physical and Mental Health

Prevalence in Primary Care Clinics 5-15% depends on population, settings Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Depression and Heart Disease Major depression: 16-23% Depressed mood: 37-35% Depression associated with: – Myocardial infarction – Angioplasty – Congestive heart failure – Coronary bypass graft surgery – Coronary artery disease Independent risk factor for sudden death and morbidity Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Depression and Cancer Associated more with pancreatic, lung, brain and oropharyngeal cancers Prevalence 25% (17-32%) in meta-analysis of 24 studies Comorbid with anxiety in half of patients Depression is associated with a decrease in treatment compliance Can also be side effects of chemotherapy/steroids Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Depression and Diabetes Up to one-third of patients with Type 2 DM has depression Depression can lead to poor compliance and poor medical outcomes Among patients with Type 2 DM, those with comorbid depression appear to be at greater risk for death from non-cardiovascular, noncancer causes compared to those without depression Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Depression in Neurological Diseases Parkinson’s disease: up to 50% Multiple sclerosis: Up to 50% Huntington’s disease: Up to 32% Epilepsy: 10-55% Post-stroke depression: 9-13% Alzheimer’s dementia: 10-32% Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Other Conditions With Increased Depression Chronic hepatitis C infection Peptic ulcer disease Inflammatory bowel disorders Fibromyalgia Chronic fatigue syndrome Sleep apnea Systemic lupus erythematosus Rheumatoid arthritis Scleroderma Pain syndromes Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Evaluation ACADEMY OF CONSULTATION-LIAISON PSYCHIATRY Psychiatrists Providing Collaborative Care Bridging Physical and Mental Health

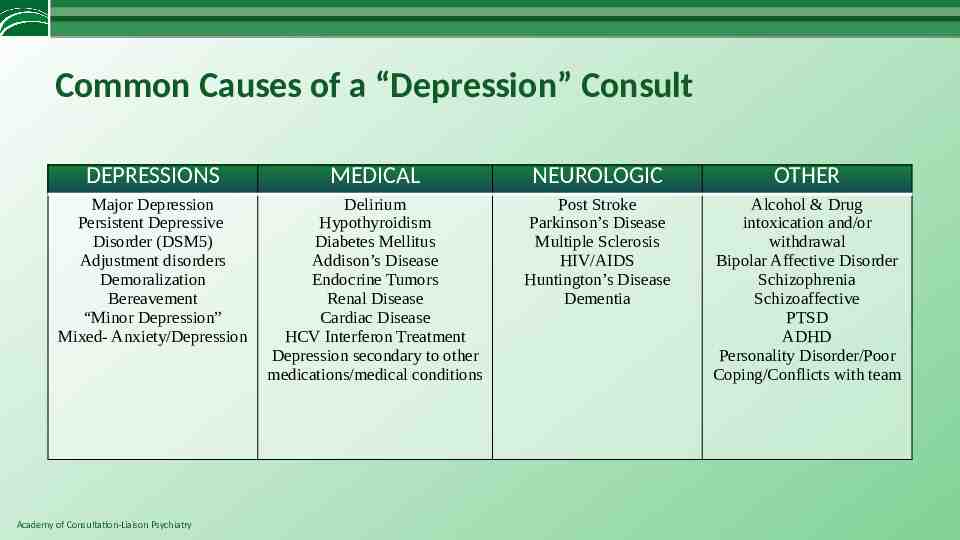

Common Causes of a “Depression” Consult DEPRESSIONS MEDICAL NEUROLOGIC OTHER Major Depression Persistent Depressive Disorder (DSM5) Adjustment disorders Demoralization Bereavement “Minor Depression” Mixed- Anxiety/Depression Delirium Hypothyroidism Diabetes Mellitus Addison’s Disease Endocrine Tumors Renal Disease Cardiac Disease HCV Interferon Treatment Depression secondary to other medications/medical conditions Post Stroke Parkinson’s Disease Multiple Sclerosis HIV/AIDS Huntington’s Disease Dementia Alcohol & Drug intoxication and/or withdrawal Bipolar Affective Disorder Schizophrenia Schizoaffective PTSD ADHD Personality Disorder/Poor Coping/Conflicts with team Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

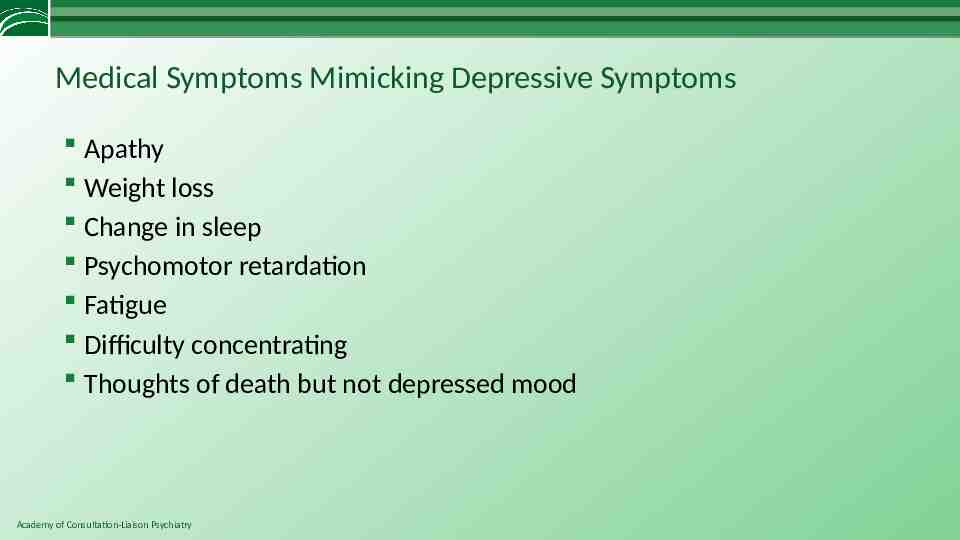

Medical Symptoms Mimicking Depressive Symptoms Apathy Weight loss Change in sleep Psychomotor retardation Fatigue Difficulty concentrating Thoughts of death but not depressed mood Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Medications commonly associated with depressive symptoms Antiepileptics * studies showing mixed/inconclusive results. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors* (Boal et al, 2016; Gerstman et al, 1996) Antihypertensives (especially clonidine, methyldopa, thiazides) Antimicrobials (amphotericin, ethionamide, metronidazole) Antineoplastics (procarbazine, vincristine, vinblastine, asparaginase) Benzodiazepines, sedative– hypnotic agents Beta-blockers* (Boal et al, 2016; Gerstman et al, 1996) Calcium channel blockers Corticosteroids Endocrine modifiers (especially estrogens, leuprolide) Interferon Isotretinoin Metoclopramide Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (especially indomethacin) Opiates Statins * (Parsaik et al, 2013)(Thompson et al, 2016) Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry (Rackley & Bostwick Psych Clin North Am, 2012)

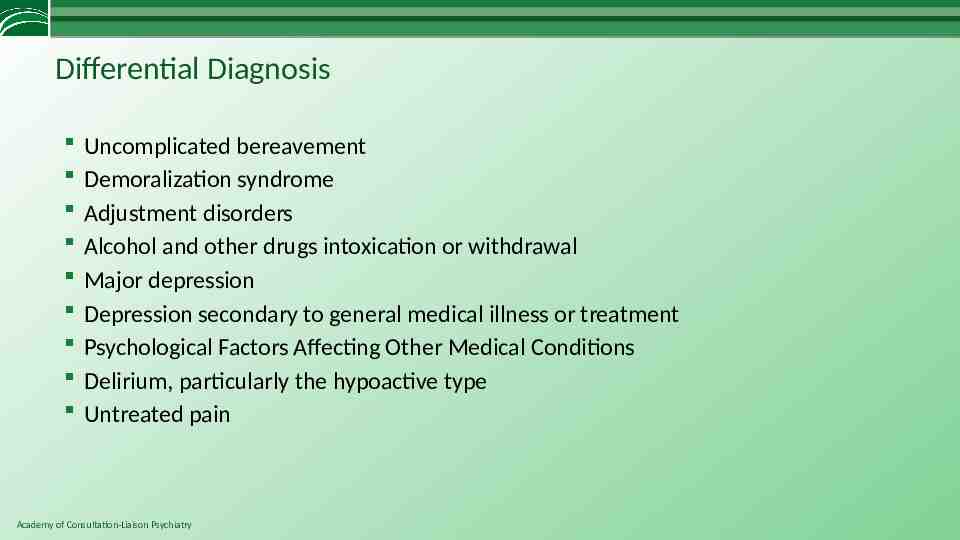

Differential Diagnosis Uncomplicated bereavement Demoralization syndrome Adjustment disorders Alcohol and other drugs intoxication or withdrawal Major depression Depression secondary to general medical illness or treatment Psychological Factors Affecting Other Medical Conditions Delirium, particularly the hypoactive type Untreated pain Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

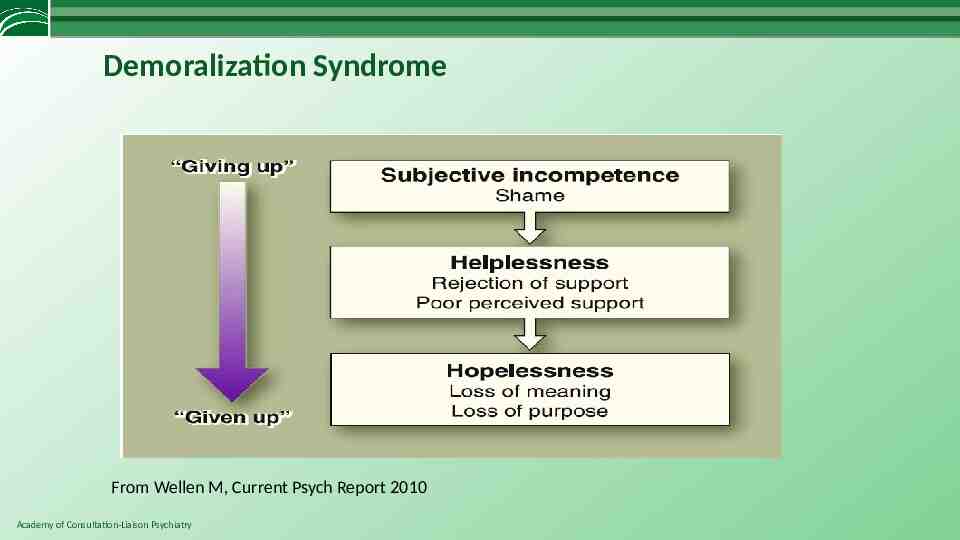

Demoralization Syndrome From Wellen M, Current Psych Report 2010 Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Demoralization May be the most common reason for psychiatric evaluation of medically-ill patients, though their physicians typically request a “depression” evaluation. Demoralization is an understandable response, albeit very distressing, to the situation (serious illness, hospitalization, agonizing treatment) Symptoms include anxiety, guilt, shame, depression, somatic complaints or preoccupation Can cause extreme frustration, anger, discouragement, non-compliance, and even thoughts of suicide / death wish Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Demoralization Perhaps more common than MDD in medical patients (Mangelli et al, J Clin Psych 2005) Some overlap with but clinically distinct from the diagnosis of major depressive disorder (Mangelli, 2005) Clues to differentiate between MDD and demoralization (Wellen, 2010) – Major Depression: Anhedonia and nihilistic thinking coming from “within” (i.e., not responding to the external situation), severe neurovegetative symptoms – Demoralization: Mood reactivity (e.g. happy when family is around, or pain is better controlled) Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Psychiatric Evaluation: Inpatient Challenges Lack of privacy in shared rooms Lack of confidentiality if family at bedside Interruptions: – Patient off to procedures – Other staff coming to see patient Patient resistant to see psychiatry Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Psychiatric Interview: Outpatient Challenges Patient may not show for the appointment – Cognitive impairment – Doesn’t want the evaluation May not have access to extensive chart Resistance to seeing psychiatry – “I’m not crazy! You need to help someone who’s really sick” – Stigma Treatment non-adherence Decision to include family if available Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Time Course and Associations ACADEMY OF CONSULTATION-LIAISON PSYCHIATRY Psychiatrists Providing Collaborative Care Bridging Physical and Mental Health

Impact of Depression in Chronic Medical Illness Increased prevalence of major depression in the medically ill Depression amplifies ( increased both number and severity of) physical symptoms associated with medical illness Comorbidity increases impairment in functioning Depression decreases adherence to prescribed regimens Depression is associated with increased heath care utilization and cost Depression is associated with adverse health behaviors (diet, exercise, smoking) Depression increases mortality associated with certain medical illness (e.g., heart disease) (adapted from Katon and Ciechanowski , 2002) Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

“It is important that somatic symptoms associated with depression should not be confused with somatoform disorders . . . Indeed, results from several surveys suggest that depression, rather than somatoform disorders, may account for most of the somatization symptoms seen in primary care.” (Tylee A, Gandhi P. The importance of somatic symptoms in depression in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry, 2005) Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Factors associated with suicide in medical-surgical patients Comorbid psychiatric illness, esp. Depression, Substance abuse, Personality disorder Chronic illness, Debilitating illness Painful illness, Disfiguring illness History of recent loss of emotional support Interpersonal problems with family or staff Impulsivity Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry (Rundell and Wise, 2000)

Service Utilization and Outcomes for Patients with Depression Increased E.R. visits Lost days from work Increased suicide attempts Higher reports of poor physical health (Johnson: 1992, Broadhead: 1990, Rundell and Wise: 2000) Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Treatment of depression in medical setting Identifying possible organic causes, e.g., thyroid, HIV, medications Appropriate management requires first establishing the most likely diagnosis that has caused depression (Rackley and Boswick, 2012) Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Treatment of depression in medical setting Utilize medications, psychotherapies, and psychoeducation Be aware of pharmacokinetic (e.g., binding, CYP 450, clearance) and pharmacodynamic (neurotransmitter receptor and transporter effects) factors Be mindful of additive sedative, anticholinergic effects from several medications ( e.g., pain meds, H2 blockers, antibiotics, antihistamines, steroids, TCAs) Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Evidenced Based Treatments for Depression Biological treatments – Antidepressant medications – Psychostimulants Psychological interventions – Cognitive behavioral therapy – Interpersonal therapy – Supportive-expressive therapy Electroconvulsive therapy Transcranial magnetic stimulation Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

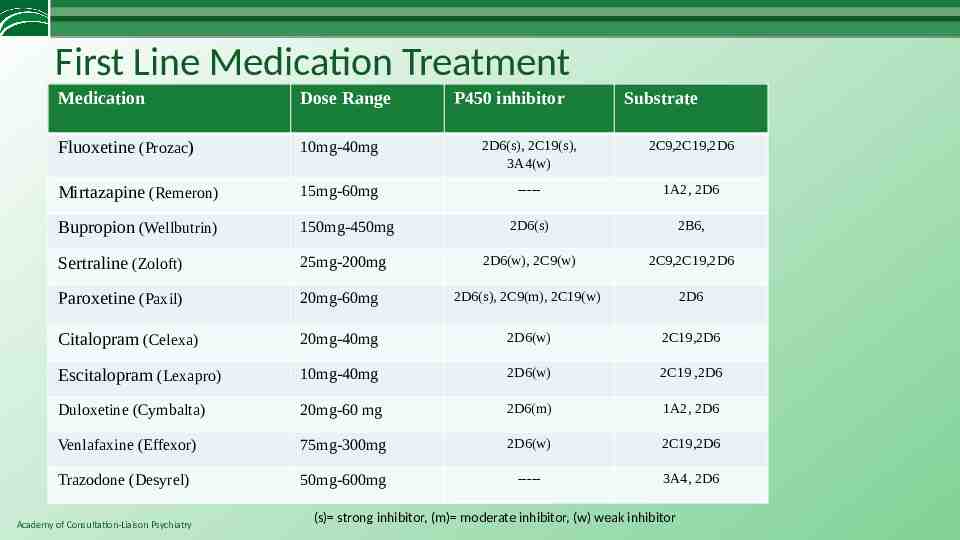

First Line Medication Treatment Medication Dose Range Fluoxetine (Prozac) 10mg-40mg 2D6(s), 2C19(s), 3A4(w) 2C9,2C19,2D6 Mirtazapine (Remeron) 15mg-60mg ----- 1A2, 2D6 Bupropion (Wellbutrin) 150mg-450mg 2D6(s) 2B6, Sertraline (Zoloft) 25mg-200mg 2D6(w), 2C9(w) 2C9,2C19,2D6 Paroxetine (Paxil) 20mg-60mg 2D6(s), 2C9(m), 2C19(w) 2D6 Citalopram (Celexa) 20mg-40mg 2D6(w) 2C19,2D6 Escitalopram (Lexapro) 10mg-40mg 2D6(w) 2C19 ,2D6 Duloxetine (Cymbalta) 20mg-60 mg 2D6(m) 1A2, 2D6 Venlafaxine (Effexor) 75mg-300mg 2D6(w) 2C19,2D6 Trazodone (Desyrel) 50mg-600mg ----- 3A4, 2D6 Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry P450 inhibitor Substrate (s) strong inhibitor, (m) moderate inhibitor, (w) weak inhibitor

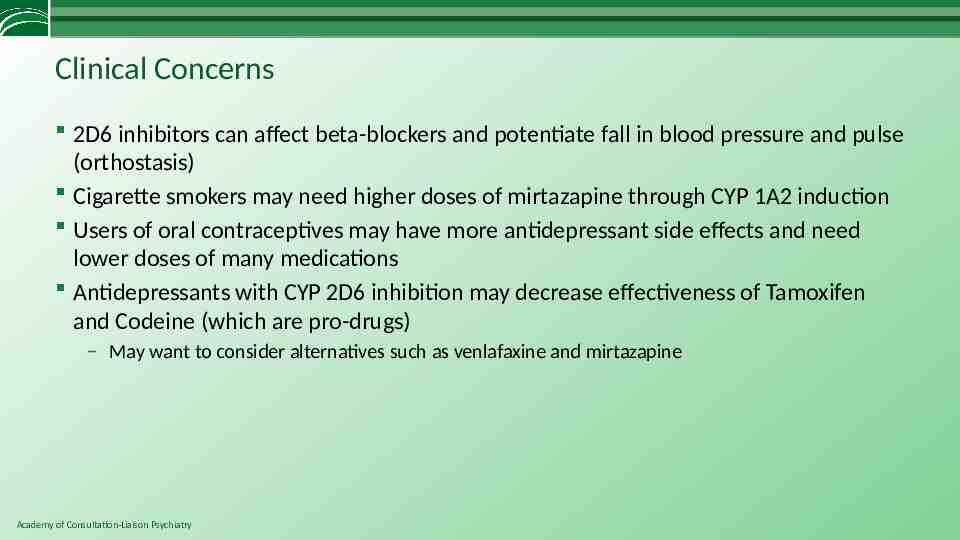

Clinical Concerns 2D6 inhibitors can affect beta-blockers and potentiate fall in blood pressure and pulse (orthostasis) Cigarette smokers may need higher doses of mirtazapine through CYP 1A2 induction Users of oral contraceptives may have more antidepressant side effects and need lower doses of many medications Antidepressants with CYP 2D6 inhibition may decrease effectiveness of Tamoxifen and Codeine (which are pro-drugs) – May want to consider alternatives such as venlafaxine and mirtazapine Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

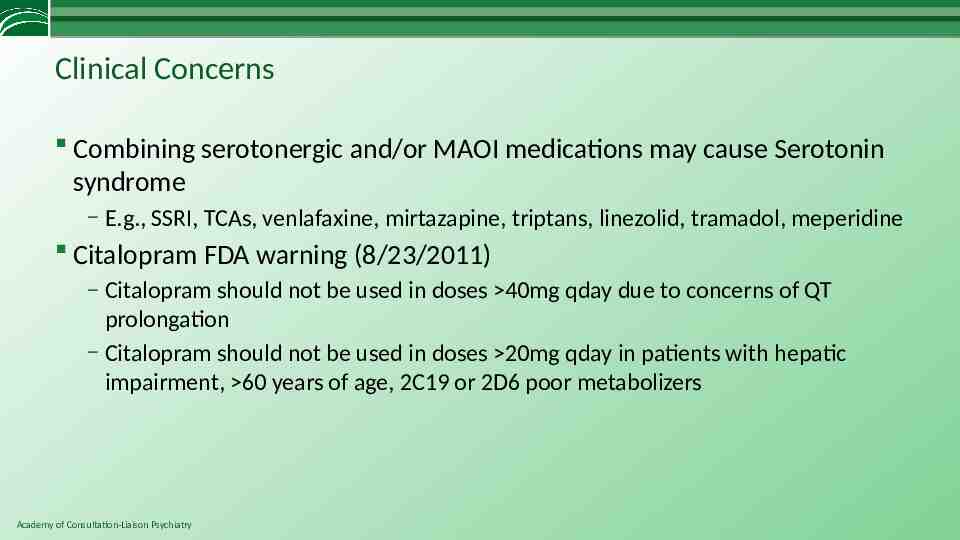

Clinical Concerns Combining serotonergic and/or MAOI medications may cause Serotonin syndrome – E.g., SSRI, TCAs, venlafaxine, mirtazapine, triptans, linezolid, tramadol, meperidine Citalopram FDA warning (8/23/2011) – Citalopram should not be used in doses 40mg qday due to concerns of QT prolongation – Citalopram should not be used in doses 20mg qday in patients with hepatic impairment, 60 years of age, 2C19 or 2D6 poor metabolizers Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

General Principles 1. Know the drug interactions of the medications you use most often 2. Look up drug interactions with any and all medicines 3. Be careful of hidden inhibitors or inducers Grapefruit juice Cigarette smoking Oral contraceptive medications Herbal medicines Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Other adjunct agents Psychostimulants can be helpful in anergic, depressed patients with cancer or organ transplants Low dose atypical antipsychotic medications, particularly quetiapine and aripiprazole, may also be helpful – Augmentation – Sleep – Anxiety/Agitation Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

In Transplant and Cancer Populations Antidepressants can be helpful: be careful of metabolism and the organ affected by the transplant or cancer Psychostimulants can be safe and effective Cognitive behavioral therapy can be helpful for depression and anxiety Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

In Chronic Kidney Disease SSRI: Sertraline considered to have least dependence on renal function Bupropion: decrease dose – authorities advise caution as increased levels may produce seizure Mirtazapine: decrease dose - 75% excreted unchanged in urine SNRI: Venlafaxine may require dose reduction in renal impairment or dialysis – Duloxetine contraindicated in severe renal disease: active metabolite may accumulate and produce confusion Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry 43

In Heart Disease SADHART: Sertraline appeared safe on cardiac parameters and effective in treating depression – Not powered to detect morbidity or mortality. – Secondary analysis show some advantage in subgroup with recurrent depression. – Subanalysis of SADHART data suggested that onset of depression before ACS, hx of MDD, baseline severity predicted sertraline response. (Glassman et al, 2002)(Joynt & O’Connor, 2005) CREATE: Citalopram effective in treating depression in cardiac patients – Interpersonal therapy not superior to placebo. – Not designed to test effects on cardiac outcomes, mortality. (CREATE, 2007) ENRICHD: CBT reduced depression modestly at 6 months, but did not reduce mortality - No benefit of CBT at 30 months. - (ENRICHD, 2003) MIND-IT: Mirtazapine safe for post-MI depression, and showed efficacy vs placebo on some primary and secondary outcome measures at 24 weeks. - Tricyclic and heterocyclic anti-depressants are not considered safe post-MI (van den Brink RH, et. al 2002) Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

In Primary Care Populations STAR*D: Protocol for treating treatment-refractory patients with medical and psychiatric co-morbidities – Modest effects starting with citalopram and moving to adjunct medications or changing medications Collaborative Care / Integrated Models – PCP, Depression care manager, consulting psychiatrist working together Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Treatment Resistance Factors ACADEMY OF CONSULTATION-LIAISON PSYCHIATRY Psychiatrists Providing Collaborative Care Bridging Physical and Mental Health

Up to 50% of patients stop antidepressants within three months (Simon,1993; Lin,1995; Sansone, 2012) Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

The Following Messages Improved Medication Compliance in the First Month 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Take the medication daily Antidepressants must be taken for 2 to 4 weeks for a noticeable effect Continue to take medicine even if feeling better Do not stop taking antidepressant without checking with the physician Provide specific instructions regarding what to do to resolve questions regarding antidepressants In addition: discussions about prior experience with antidepressants and discussions about scheduling pleasant activities also were related to early adherence Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Take Home Messages Depression in medically ill can be complex and multifactorial, and needs a thorough evaluation Check drug-drug interactions for all the patient’s medications – Computer programs, mobile apps widely available Medical conditions and depression affect each others’ symptoms and course, and affect the patient’s health related quality of life Depression may be successfully treated by addressing medical conditions and medical drugs, and utilizing biological, psychological and educational interventions Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

References Boal AH, et al. Monotherapy with major antihypertensive drug classes and risk of hospital admissions for mood disorders. Hypertension 2016; 1132-1138. Bukberg J, Penman J, Holland J. Depression in hospitalized cancer patients. J Psychosomatic Medicine 1984; 46(3):199-211. Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, et al. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA 1990;264(19):2524-8. Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Freedland KE, et.al. Depression and late mortality after myocardial infarction in the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) study. Psychosom Med 2004;66(4):466-74. Coleman SM, Katon W, Lin E.Depression and Death in Diabetes; 10-Year Follow-Up of All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality in a Diabetic Cohort Psychosomatics 2013 ;54,( 5) :428-436 Cozza KL, Armstrong SC, Oesterheld JR: Concise Guide to Drug Interaction Principles for Medical Practice: Cytochrome P450s, UGTs, P-Glycoproteins, Second Edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2003 Flockhart DA. Drug Interactions: Cytochrome P450 Drug Interaction Table. Indiana University School of Medicine (2007). http://medicine.iupui.edu/clinpharm/ddis/" Accessed October 26, 2017. Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M. Depression following myocardial infarction. Impact on 6-month survival. JAMA 1993;270(15):1819-25. Gerstman BB, et al. The incidence of depression in new users of beta-blockers and selected antihypertensives. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 1996; 49(7):809-815. Glassman AH, O'Connor CM, Califf RM, et.al. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA 2002;288(6):701-709. Griffith JL, Gaby L. Brief psychotherapy at the bedside: countering demoralization from medical Illness. Psychosomatics. 2005 Mar-Apr;46(2):109-16.5. Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

References Horwath E, Johnson J, Klerman GL, et al. Depressive symptoms as relative and attributable risk factors for first-onset major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 1992;49(10):817-23. Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA 1992; 267(11):1478-83. Joynt KE, O’Connor CM. Lessons from SADHART, ENRICHD, and other trials. Psychosomatic Medicine 2005; 67(1): S63-S66. Katon W, Ciechanowski P. Impact of major depression on chronic medical illness. J Psychosom Res. 2002 Oct;53(4):859-63 Levenson JL. Textbook of Psychosomatic Medicine, Second edition . The American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. Washing DC, 2011. Lin EHB, VonKorff M, Katon W, Bush W, Simon T, et al. The role of the primary care physician in patients’ adherence to antidepressant therapy. Medical Care 1995, 33(1): 67-74. Parsaik AK et al. Statin use and risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorder 2014; 160:62-67. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 1993; 50(2): 85-94. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Antidepressant adherence: are patients taking their medications? Innov Clin Neurosci 2012; 9(4-5):4146. Simon GE, Katon WJ, Von Korff M, et.al. Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. Am. J. Psych. 2001; 158(10): 1638-1644. Slavney PR. Diagnosing demoralization in consultation psychiatry. Psychosomatics 1999;40(4):325-9. Thompson PD, et al. Statin-associated side effects. Journal of American College of Cardiology 2016;67:2395-2410. Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

References Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. American Journal of Psychiatry 2006; 163(1): 28-40. Wells KB; Burnam MA; Rogers W; Hays R; Camp P. The course of depression in adult outpatients. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Archives of General Psychiatry 1992; 49(10): 788-94. Writing Committee for the ENRICHD Investigators. The effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the enhancing recovery in coronary heart disease patients (ENRICHD) Randomized Trial. JAMA 2003; 289: 3106-3116. Writing Committee for the CREATE Investigators. Effects of citalopram and interpersonal psychotherapy on depression in patients with coronary artery disease. The Canadian Cardiac Randomized Evaluation of Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Efficacy (CREATE) Trial. American Medical Association 2007; 297(4): 367-379. Van den Brink RH, et. al. Treatment of depression after myocardial infarction and the effects of cardiac prognosis and quality of life: rational and outline of the Myocardial Infarction and Depression-Intervention trial (MIND-IT). Am. Heart J 2002: 144: 219225. Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry