PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS IN STROKE SELFMANAGEMENT FOR OCCUPATIONAL

44 Slides2.10 MB

PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS IN STROKE SELFMANAGEMENT FOR OCCUPATIONAL THERAPISTS Riqiea Kitchens, PhD, OTR, BCPR, CSRS TOTA GCED Presentation August 2019

OBJECTIVES To describe the key components of selfmanagement (SM) To identify role of occupational therapy in a stroke specific selfmanagement program (SSMP) To identify strategies to apply SM principles in group and individual treatment settings

SELF- MANAGEMENT Responsibility for the day to day management of a condition through engagement in a health promoting activity (Lorig and Holman, 2003)

THEORY Theory of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977) – A belief in one’s ability to accomplish a certain task Performance accomplishments Vicarious experiences (Modeling) Verbal persuasions Emotional arousal

SELF- Self-management is MANAGEMENT composed of 3 tasks: – Medical management – Maintaining, changing, and creating meaningful behaviors or life roles – Emotional management

SELF- Chronic Disease SelfMANAGEMENT Management Program PROGRAMS (CDSMP) – Weekly for 6 weeks, 2.5 hours each session Studied in general and chronic conditions including: arthritis, diabetes, chronic pain, HIV specific programs, stroke*

SELF- SM Programs address 5 MANAGEMENT core skills: PROGRAMS – Problem solving – Decision making – Finding and utilizing resources – Forming partnerships with health care providers – Making and implementing a plan of action

How is this relevant to OT practice

OCCUPATIONAL Occupations (IADLs) THERAPY Health management and PRACTICE maintenance FRAMEWORK, “Developing, managing, rd 3 EDITION and maintaining routines for health and wellness promotion, such as physical fitness, nutrition, decreased health risk behaviors, and medication routines (AOTA, 2014)”

So, why stroke?

BACKGROUND Leading cause of long-term disability in the U.S. (American Stroke Association) 1 in 4 persons who have a stroke will have a recurrent stroke (Roger, et. al 2012) Persons with multiple risk factors have greater risk of recurrence stroke (Go, et. al 2013) Estimated costs associated with stroke costs the United States an estimated 36.5 billion annually (Go, et al 2013) Addressing lifestyle factors can reduce stroke risk (Healthy People 2020)

What does the research say?

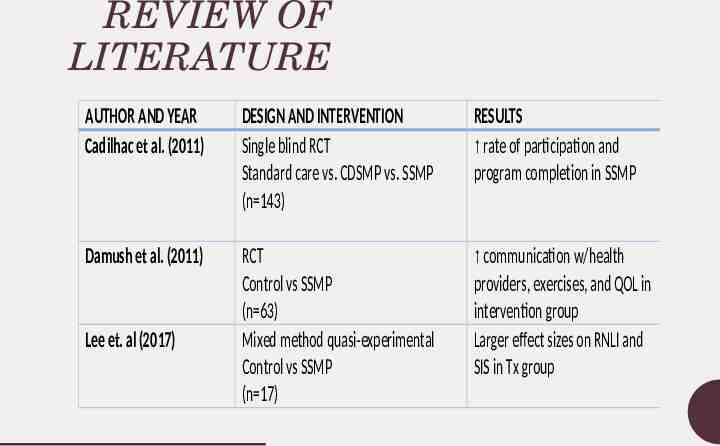

REVIEW OF LITERATURE AUTHOR AND YEAR Cadilhac et al. (2011) DESIGN AND INTERVENTION Single blind RCT Standard care vs. CDSMP vs. SSMP (n 143) RESULTS rate of participation and program completion in SSMP Damush et al. (2011) RCT Control vs SSMP (n 63) Mixed method quasi-experimental Control vs SSMP (n 17) communication w/health providers, exercises, and QOL in intervention group Larger effect sizes on RNLI and SIS in Tx group Lee et. al (2017)

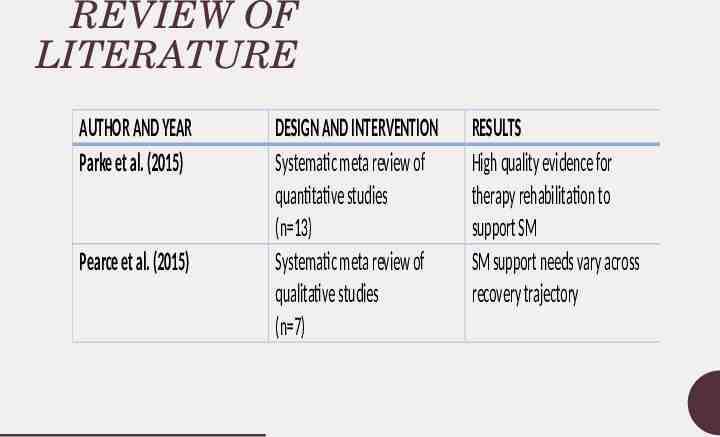

REVIEW OF LITERATURE AUTHOR AND YEAR Parke et al. (2015) Pearce et al. (2015) DESIGN AND INTERVENTION Systematic meta review of quantitative studies (n 13) Systematic meta review of qualitative studies (n 7) RESULTS High quality evidence for therapy rehabilitation to support SM SM support needs vary across recovery trajectory

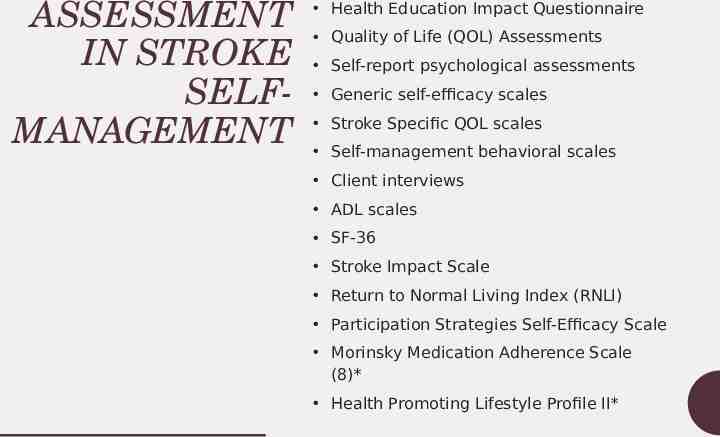

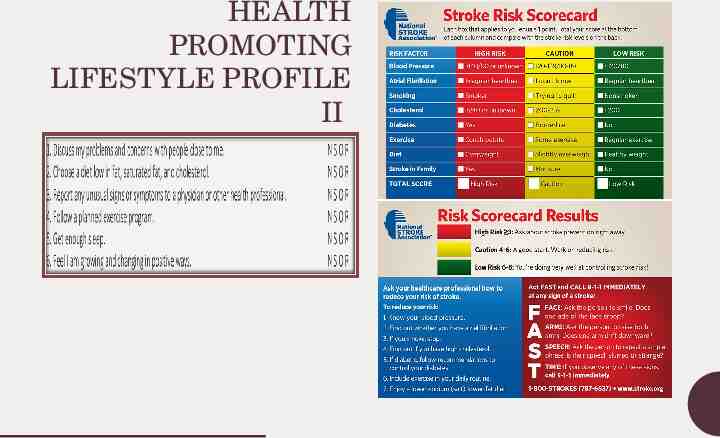

ASSESSMENT IN STROKE SELFMANAGEMENT Health Education Impact Questionnaire Quality of Life (QOL) Assessments Self-report psychological assessments Generic self-efficacy scales Stroke Specific QOL scales Self-management behavioral scales Client interviews ADL scales SF-36 Stroke Impact Scale Return to Normal Living Index (RNLI) Participation Strategies Self-Efficacy Scale Morinsky Medication Adherence Scale (8)* Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile II*

ASSESSMENT IN STROKE SELFMANAGEMENT A standardized assessment tool for self-management in stroke populations has not yet been established

CLINICAL CASES GROUP TREATMENT EXAMPLE

OCCUPATIONAL PROFILE HANNAH* 49 y/o Caucasian female College educated Divorced ADL- Mod I IADL - performed with assistance of friend Social participation – attending weekly Bible study

PROBLEM AREAS PMH includes – Type 2 Diabetes – Morbid obesity – Physical Inactivity – Former smoker – 2 prior strokes – Short term memory deficits

OT GOALS Education on stroke risk factors Risk factor modification Medication adherence Example: In 6 weeks client will identify 1 personal risk factor and develop 1 strategy to modify risk factor to decrease risk of recurrent stroke.

PATIENT GOAL To learn how to control diabetes to prevent another stroke

OT ASSESSMENT S Stroke Risk Score Card Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile II (HPLP II) Morinsky Medication Adherence Scale

HEALTH PROMOTING LIFESTYLE PROFILE II

GROUP PROGRAM Interdisciplinary 12 week SSMP, cohort format Weekly 1.5 hr group sessions 3 Modules: – Building Awareness – Building Knowledge and Making Changes – Building Carryover and Accountability

APPLYING CORE SKILLS Weekly log Goal setting STG and LTG Group activities included: problem solving and decision making, discussion of coping skills, meal planning, food labels, tailored exercise

OUTCOMES/ RESULTS 5 stroke risk factors met – High Risk Increased HPLP II score (2.48 to 3.51) Improved portion control and food selection Improved control of Diabetes, decreased insulin medication

CLINICAL CASES INDIVIDUAL TREATMENT EXAMPLE

OCCUPATIONAL PROFILEMARTIN* 63 y/o African American male Single PLOF: Independent Employment: truck driver Stroke onset: 2 months

PROBLEM AREAS High blood pressure Atrial fibrillation Tobacco dependence Diabetes Type 2 – uncontrolled Express aphasia Right hemiparesis and ataxia Limited and inconsistent social support Emotional distress

OT ASSESSMENT Standard outpatient evaluation

GOALS OT goals* – Education on personal stroke risk factors – Risk factor modification – Coping skills Example: In 4 visits Pt. will keep a daily blood sugar log to improve self monitoring of diabetic condition. Patient goal- to return to PLOF

OT INTERVENTIONS Weekly 1:1 visits x 8 weeks 45-60 min each session SM education integrated into rehab plan

APPLYING THE CORE SKILLS Identifying and utilizing community resources Communicating with health care providers and caregivers Problem solving and decision making Goal setting and health tracking Emotional management

OUTCOMES/ RESULTS Increased self-monitoring blood sugar levels using daily log – Blood sugars decreased from 200-300s (non fasting) to 150-180s Dietary changes Improved social participation Improve communication with health care providers Increase mood and initiative

This is great, but is it billable? Absolutely!

BILLING AND CODING CPT code 97150: Therapeutic Procedure or Group (2 or more individuals)- Untimed code CPT code 97535: Self-care/Home management training – Timed code for direct 1:1 treatment – ADL training reasonably and medically necessary to restore or improve the functioning of the patient

POINTS TO CONSIDER What type of patient is appropriate? – Desire and capability to take an active role in their own healthcare What type of patient is not appropriate? When do I start providing stroke self-management interventions?

CONCLUSION SSMP is beneficial for patients to improve self-efficacy and participation in their own health care in a group or individual OT is in a unique position to meet this need and can readily incorporate these principles into clinical practice. “an attitude can’t cure chronic illness but a positive attitude and certain SM skills can make it much easier to live with”- Lorig, 2012

Hannah’s Caregiver: “ After the program you thought, well, I can make a difference, I can change some things made you realize that, you know, you can control some of this ”

Acknowledgements Harris Health System

QUESTIONS?

REFERENCES American Occupational Therapy Association (2014). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process, 3rd edition. AJOT, 68(Supplemental 1), S1-S551. Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215. Cadilhac, D. A., Hoffman, S., Kilkenny, M., Lindley, R., Lalor, E., Osborne, R. H., Batterbsy, M. (2011). A phase II multicentered, single-blind, randomized, controlled trial of the stroke self-management program. Stroke, 42, 1673-1679. DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.601997 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013). Stroke Facts. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/stroke/facts.htm Damush, T. M., Ofner, S., Yu, Z., Plue, L., Nicholas, G., Williams, L. S. (2011). Implementation of a stroke selfmanagement program: A randomized controlled pilot study of veterans with stroke. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 1, 561-572. DOI: 10.1007/s13142-011-0070-y Editorial: Self-management interventions: Using an occupational lens to rethink and refocus. [Editorial]. (2013). Australian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 60, 1-2. DOI: 10.1111/1440-1630.12032

REFERENCES Lee, D., Fischer, H., Zera, S., Robertson, R. Hammal, J. (2017). Examining a participation-focused stroke selfmanagement intervention in a day rehabilitation setting. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. DOI:10.1080/10749357.2017.1375222 Lorig, K., Holman, H. (2003). Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 26(1), 17. Lorig, K., Holman, H., Sobel, D., Laurent, D., Gonzalez, V., Minor, M. (2012). Living a Healthy Life with Chronic Conditions: Self-management of heart disease, arthritis, emphysema, and other physical and mental health conditions, 4th ed. Bull Publishing: Boulder, CO Parke HL, Epiphaniou E, Pearce G, Taylor SJC, Sheikh A, Griffiths CJ, et al. (2015). Self-management support interventions for stroke survivors: A systematic metareview. PLoS ONE 10(7): e0131448. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131448 Pearce G, Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E, Parke HL, Heavey E, Griffiths CJ, et al. (2015). Experiences of selfmanagement support following a stroke: A metareview of qualitative systematic reviews. PLoS ONE 10(12): e0141803. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0141803

CONTACT ME! E-mail: [email protected] Twitter: @kitchensOT Linked in: Riqiea Kitchens