Chronic Pain ChangeThatMatters.umn

59 Slides4.39 MB

Chronic Pain www.ChangeThatMatters.umn.edu

Patient Scenario Imagine you are looking ahead at your schedule for the day, and you see a patient, who is new to you, on your schedule. You open their chart, and see the visit is for “chronic pain.” What thoughts go through your head? What emotions do you feel?

Brief Overview

Pain Definitions "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience arising from actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage" (International Association for the Study of Pain, 2014) Acute pain lasts for days to a month after a physiologic insult or injury Subacute pain lasts from one to three months after an injury Chronic pain is pain that persists longer than three months

Acute Pain Normal, predicted physiologic response to an adverse chemical, thermal or mechanical insult associated with surgery, trauma or acute illness/injury Results from the activation of the pain receptors (nociceptors) at the site of tissue damage Plays a vital survival role for the individual as it provides a warning that something is wrong and prompts remedial action Acute pain is thus referred to as having "biologic utility”

Chronic Pain Pain that persists beyond the normal time expected for healing Initial peripheral pain generation is followed by central neuroplastic changes in the brain and spinal cord Pathophysiologic changes in the central nervous system along with a complex interplay of emotional, psychological and social factors contribute to an individual's worsening ability to function Persistent, underlying discomfort punctuated with acute flare-ups that may last minutes to hours to several days and lead to impaired functioning. These episodes do not reflect new tissue injury and are almost always self-limiting Chronic pain has no biologic utility and offers the individual little protection from further injury

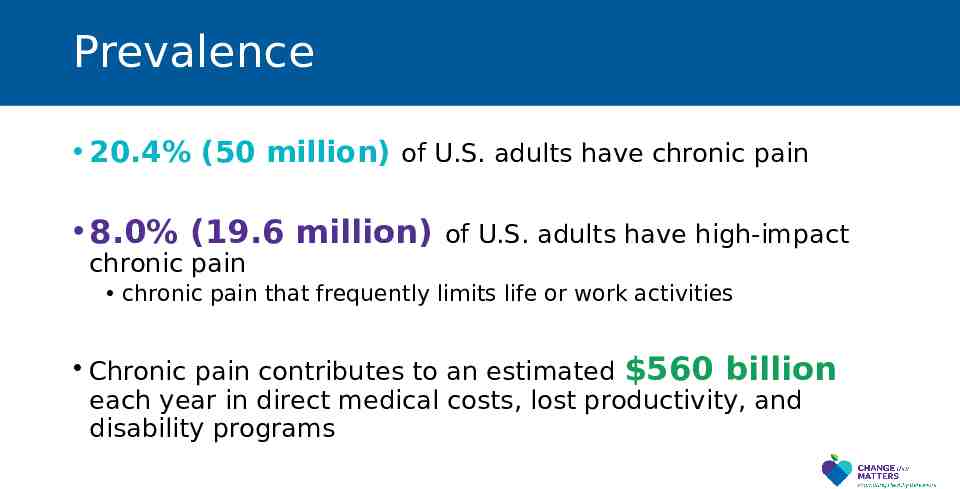

Prevalence 20.4% (50 million) of U.S. adults have chronic pain 8.0% (19.6 million) chronic pain of U.S. adults have high-impact chronic pain that frequently limits life or work activities Chronic pain contributes to an estimated 560 billion each year in direct medical costs, lost productivity, and disability programs

Factors associated with higher prevalence of chronic pain Poverty Less than high school education Public health insurance Women Previously worked but not currently employed Rural residents Non-Hispanic whites

Co-occurring Concerns Restrictions in mobility Restrictions in daily activities Poor perceived health Reduced quality of life Anxiety Depression Opioid dependence

Assessment and Medical Intervention

Pain Generators Neuropathic pain Musculoskeletal pain Inflammatory pain Visceral pain Opioid-induced pain

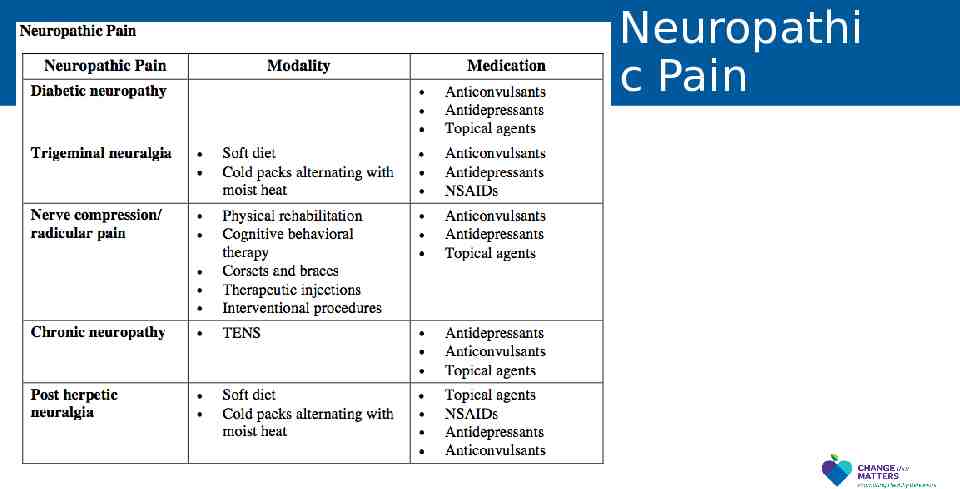

Neuropathic Pain Pain caused by a lesion or disease of the central or peripheral somatosensory nervous system Examples of conditions: Diabetic peripheral neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia Historical features: Pain characterized as burning, stinging or "pins and needles" sensation Physical exam findings: Allodynia (pain due to a stimulus that does not provoke pain) Hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to pain) with or without sensory or motor deficits

Neuropathi c Pain

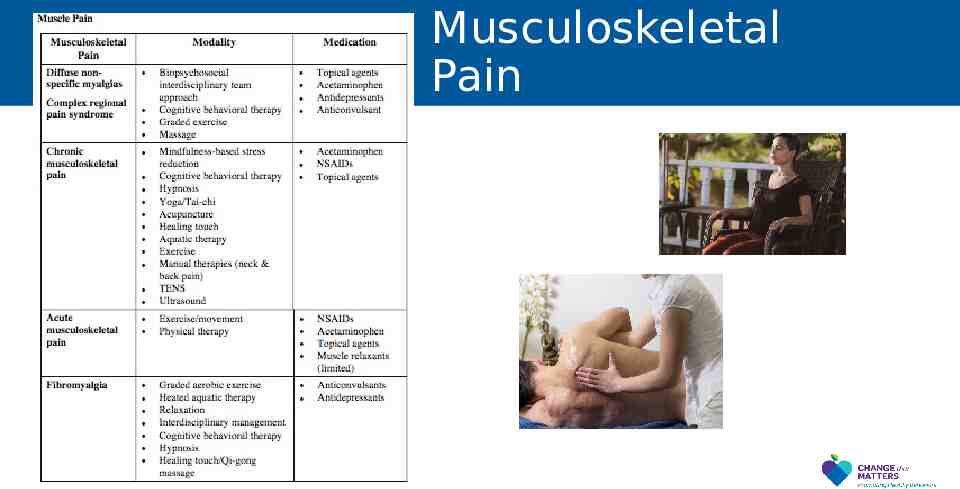

Musculoskeletal Pain Pain caused by a lesion or disease of the musculoskeletal system including muscles, ligaments, tendons, cartilaginous structures and joints Examples of conditions: Axial or radicular spine pain, degenerative joint disease Historical features: Anatomically localized or more diffuse pain characterized as aching, dull with or without sharp exacerbations with movement or weight-bearing activities Physical exam: Localized tenderness, joint deformity with or without weakness attributed to pain

Musculoskeletal Pain

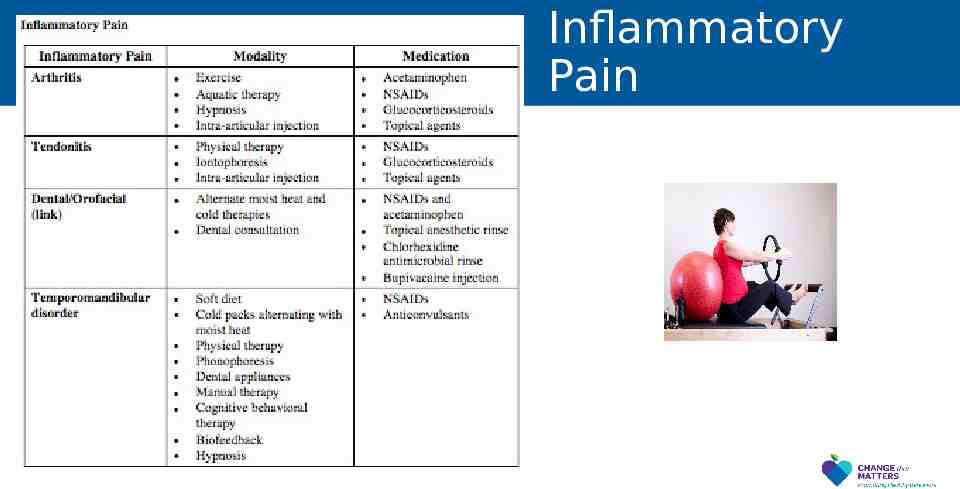

Inflammatory Pain Pain caused by an inflammatory process (e.g., infection, autoimmune), which is generally associated with the infiltration of immune cells and tissue damage Examples of conditions: Rheumatoid arthritis, infected joint Historical features: Progressive pain characterized as sharp, lancinating with or without increased pain with movement of the involved anatomical region or signs and symptoms of an infectious process Physical exam: Tenderness, erythema, swelling, increased warmth of the involved anatomical region with or without signs and symptoms of an infectious process

Inflammatory Pain

Visceral Pain Pain caused by a lesion or disease involving the thoracic, abdominal or pelvic viscera Examples of conditions: Dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome, endometriosis, non-cardiac chest pain, chronic angina Historical features: Intermittent pain characterized as sharp or dull with increased pain with engagement of the involved anatomical region with or without signs and symptoms of an infectious process Physical exam: Localized tenderness of the involved anatomical region with or without signs and symptoms of an infectious process

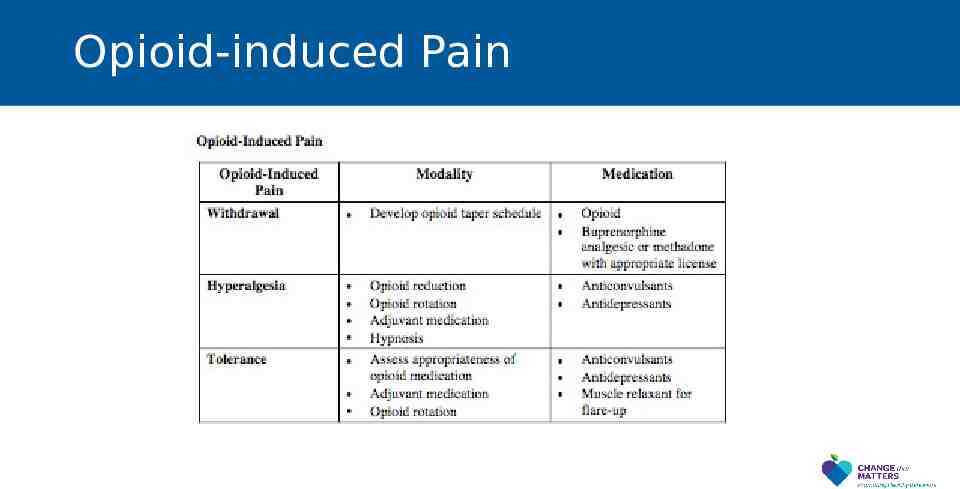

Opioid-induced Pain Pain caused by adaptation of the opioid receptors to chronic exposure to opioids or a physiologic reaction to withdrawal of opioids or as a side effect of opioids Examples of conditions: Opioid withdrawal, opioid-induced hyperalgesia and opioid tolerance Historical features: Dependent upon condition Physical exam: Dependent upon condition

Opioid-induced Pain

Addressing Chronic Pain Conduct a comprehensive medical assessment initially, periodically and whenever there is a lack of improvement - Use of validated tools to assess quality-of-life, function and pain - Determination of the pain generator - Assessment for comorbidities - Discussion of patient barriers

Addressing Chronic Pain Active patient engagement in the creation and execution of the biopsychosocial treatment plan is a critical factor of success Develop a treatment plan for pain that uses all available modalities and avoids making medications, especially opioids, the sole focus of treatment Treatment should focus on restoration of function, not elimination of pain

Assessment Tools

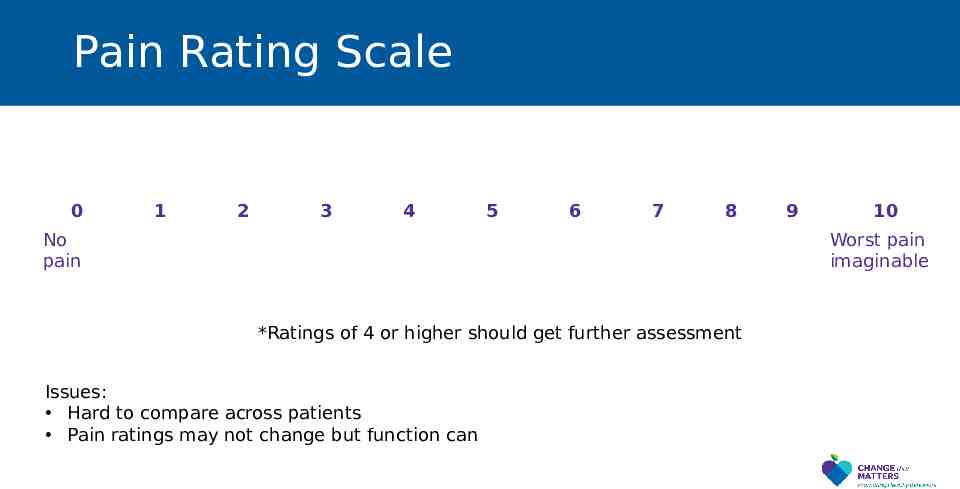

Pain Rating Scale 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 No pain 9 10 Worst pain imaginable *Ratings of 4 or higher should get further assessment Issues: Hard to compare across patients Pain ratings may not change but function can

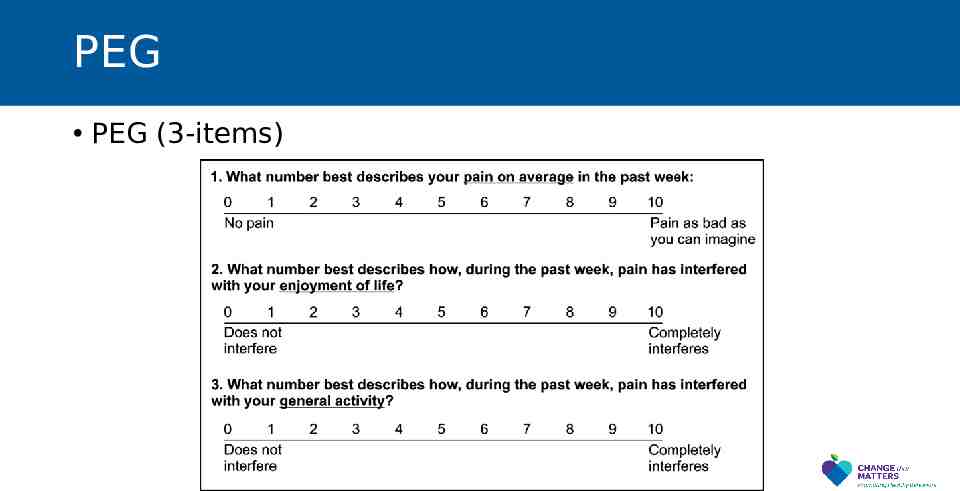

PEG PEG (3-items)

Evidence-Based Treatments

Evidence-based Behavioral Interventions Developing realistic expectations and goals Relaxation training Cognitive behavioral therapy Activity pacing Family interventions

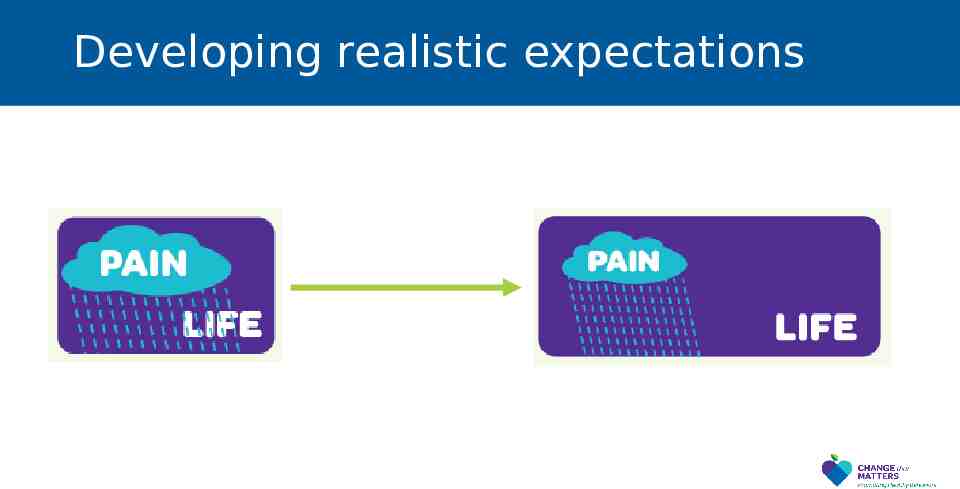

Developing realistic expectations Sometimes patients believe that treatment will substantially decrease or eliminate pain Shift goal to: Increased distress tolerance Improved ability to achieve valued goals (despite pain) Decrease importance of medications as the primary (or sole) method of managing pain Increase physical activity across multiple life domains

Developing realistic expectations

Relaxation Training Relaxation exercises can lead to decreased perception of pain Provide rationale Practice relaxation exercises Deep breathing Progressive muscle relaxation Autogenic relaxation Sources YouTube Apps (e.g., Headspace, Calm, Breathe) Therapy

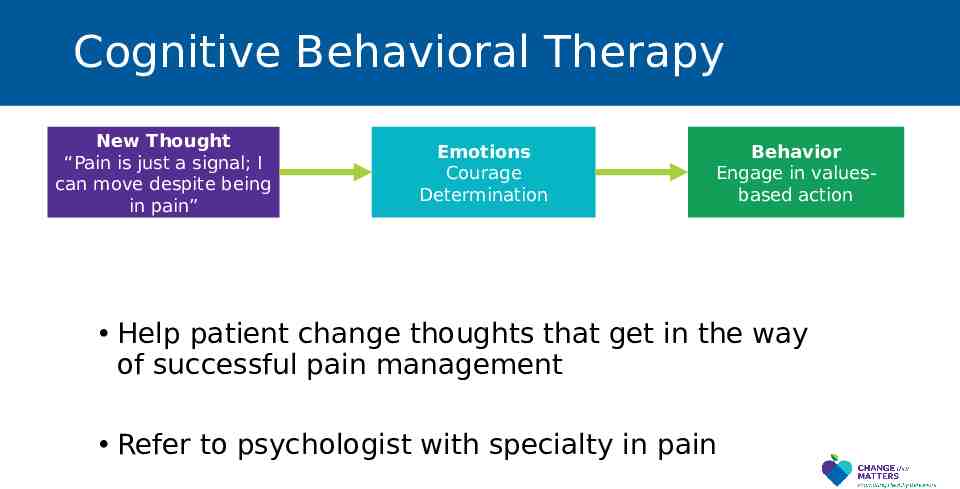

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Target maladaptive thoughts related to pain “This pain should completely resolve.” “My functioning should completely return to normal.” “My pain is a warning that I should stop doing activities.” “I am a burden to others.” “My future is bleak if my pain continues.” Thought “Pain means to stop doing activity” Emotions Fear Relief Sadness Behavior Disengage Stop moving

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy New Thought “Pain is just a signal; I can move despite being in pain” Emotions Courage Determination Behavior Engage in valuesbased action Help patient change thoughts that get in the way of successful pain management Refer to psychologist with specialty in pain

A Note on Pain and Suffering Pain is the physical signal; Suffering is the emotional experience Patients who experience more negative emotion about the pain (i.e., who suffer) actually experience worse pain It may be helpful to help patients distinguish the difference between pain and suffering

Pain and Depression There is a significant overlap between & depressive symptoms pain Approximately 34% of people in a depressive episode experience “severe pain” 60% of patients with chronic pain meet criteria for depression CBT can treat depression and pain simultaneously

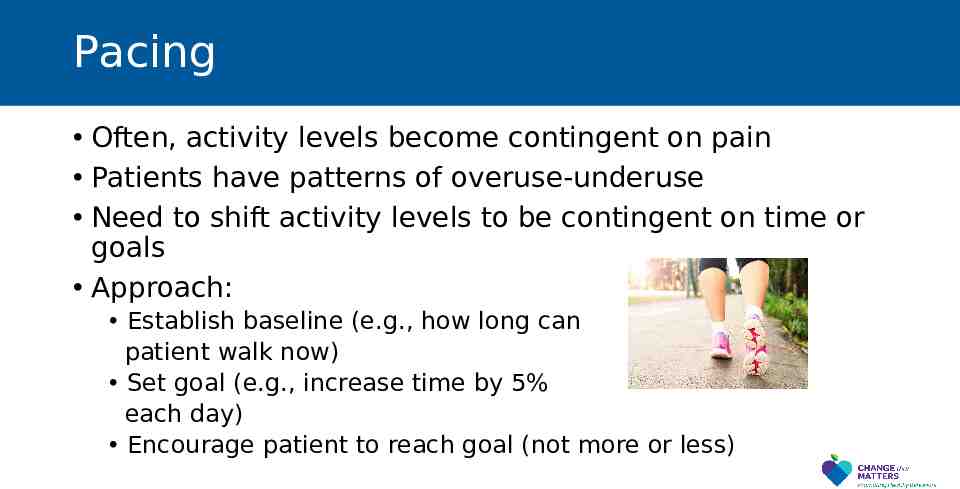

Pacing Often, activity levels become contingent on pain Patients have patterns of overuse-underuse Need to shift activity levels to be contingent on time or goals Approach: Establish baseline (e.g., how long can patient walk now) Set goal (e.g., increase time by 5% each day) Encourage patient to reach goal (not more or less)

Family Interventions Sometimes family members’ response to patients’ pain can influence patients’ pain experience Encourage family members to: Support patient self-management Ignore unhelpful coping behaviors, such as resting and inactivity Reward positive behaviors, such as exercise and paced activities Decrease hovering and overhelping

Tool for Addressing in Primary Care

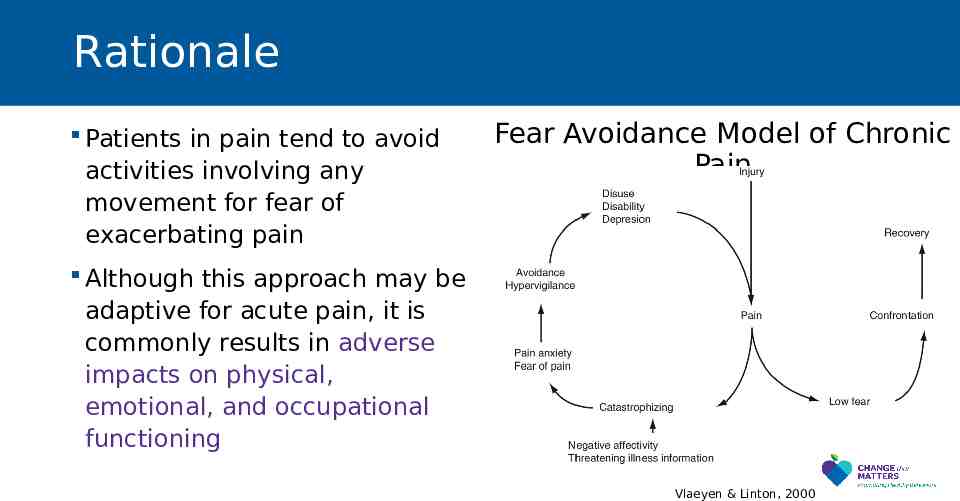

Rationale Patients in pain tend to avoid activities involving any movement for fear of exacerbating pain Fear Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain Although this approach may be adaptive for acute pain, it is commonly results in adverse impacts on physical, emotional, and occupational functioning Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000

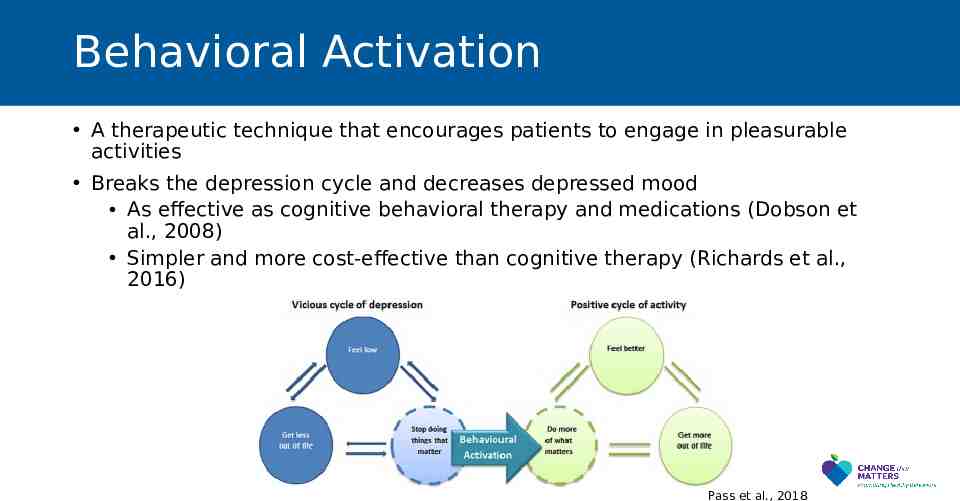

Behavioral Activation A therapeutic technique that encourages patients to engage in pleasurable activities Breaks the depression cycle and decreases depressed mood As effective as cognitive behavioral therapy and medications (Dobson et al., 2008) Simpler and more cost-effective than cognitive therapy (Richards et al., 2016) Pass et al., 2018

Values Values are the things we find most meaningful or important to us in life Patients with chronic pain often disconnect from valuable activities and focus on the pain, which can make people feel “off” Values-based interventions ask patients to reflect on what is valuable to them and encourage increased engagement in valued activities

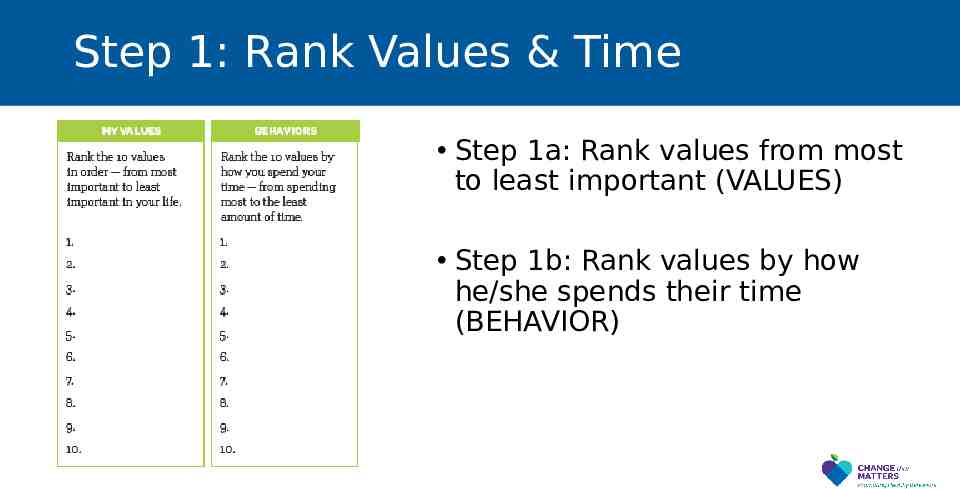

Step 1: Rank Values & Time Step 1a: Rank values from most to least important (VALUES) Step 1b: Rank values by how he/she spends their time (BEHAVIOR)

Step 2: Identify discrepancies Ask patient to reflect on what they notice, including differences between the two lists What value do they want to spend more time on?

Step 3: Set a SMART goal 1. Pick one value area to work on. What is a specific goal that they can meet in the next two weeks that works on this goal? 2. Specify where, when, how much, and with whom. 3. Elicit potential barriers; problem solve possible solutions. 4. Set follow-up with patient to see how it went.

Patient Handout

Noteworthy Features of the Handout Tips to manage chronic pain Setting realistic expectations Values assessment Setting SMART values-based behavioral activation goal Message to instill hope

EHR Templates

Documentation Template Assess: Top three values: *** Identified discrepancies: *** Plan: Specific goal: *** Referrals: (BFM behavioral health, outside MH facility, interdisciplinary chronic pain program, other ***) Follow-up: *** Change that Matters Managing Chronic Pain handout given. *** minutes spent counseling patient on managing chronic pain to improve overall health

After Visit Summary (AVS) Template Today we talked about ways to manage your chronic pain. You set a goal to *** We will follow up on this plan at your next appointment. Here are some other ideas to manage chronic pain:

AVS Template (cont) Use relaxation and deep breathing strategies to calm your mind and body. Many phone apps and online videos can guide you through progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, or meditation. Move! Regular physical activity can help with muscle aches, pain, and depression. Pace yourself and listen to your body. Distract yourself. Focusing on the pain can make it feel worse. Get your mind off of the pain by doing a fun activity. Use heat or ice. Take a warm shower or bath or use a heating pad for 20 minutes a day. Ice packs or cold showers may also help. Consider alternative therapies. Try chiropractic care, acupuncture, or osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT). Try physical therapy. Stretches and strengthening exercises can be helpful. Consider therapy. Counseling can help you learn strategies to manage pain and get back to enjoying life again.

Structured Practice

Practice Activity 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Partner up! Have one person be the physician, the other the patient Use pamphlet and EHR template (take 5-10 minutes) Patient: Rank values & the way you spend your time Physician – prompt patient to reflect on differences, brainstorm ways to engage in one value area 6. Co-create an action plan for the patient to do a valued activity in the next week

Responding to Common Challenges

But Doc My pain is so bad I don’t think I can do it. Acknowledge pain is unavoidable Encourage patient to do what he/she can, despite being in pain The goal is to live life, with pain

But Doc I’ve avoided (behavior) for so long. It’s going to be really hard to try again Acknowledge avoidance as understandable. Help patient balance short-term benefits of avoidance with long-term negative consequences Remind patient WHY he/she wants to do this (tie to his/her values) Encourage patient to act even if he/she doesn’t feel like it Set specific goal

Resources for Further Learning

Clinical Practice Guidelines ICSI Health Care Guideline: Pain: Assessment, Non-Opioid Treatment Approaches and Opioid Management Care for Adults (September 2019): https://www.icsi.org/guideline/pain/ Owen GT, Bruel BM, Schade CM, et al. Evidence-based pain medicine for primary care physicians. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Center). 2018;31(1):37-47. doi:10.1080/08998280.2017.1400290

Books De Mesa C, Sheth SJ, Keenan C, McCarron RM, John J. Primary care pain management. 2020; China: Wolters Kluwer. Caudill MA. Managing pain before it manages you (4th Ed.). 2016; New York, NY: The Guilford Press. Otis JD. Treatments that work: Managing chronic pain: A cognitive behavioral approach. 2007; New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Change That Matters Team Stephanie A. Hooker, PhD, MPH (co-PI) Michelle D. Sherman, PhD, ABPP (co-PI) Katie Loth, PhD, MPH Kacey Justesen, MD Sam Ngaw, MD Marc Uy, BA, MPH Jean Moon, PharmD, BCACP Andrew Slattengren, DO Anne Doering, MD

Special Thanks University of Minnesota Academic Health Center and National Institute for Integrated Behavioral Health for financial support for their development and evaluation of Change that Matters