Charlotte Turner Smith Issue 2: Refugees

18 Slides605.04 KB

Charlotte Turner Smith Issue 2: Refugees

Wolfson, Susan J. “Charlotte Smiths ‘Emigrants’: Forging Connections at the Borders of a Female Tradition.” Elaine Showalter tracked British women novelists from the 1840s to the 1960s across three phases: o The feminine - Imitating the prevailing modes of a dominant, mostly male-authored tradition, o The feminist - protesting internalized norms and advocating minority rights and values, o The female- self discovery invigorated by political liberty. Twenty years later, Anne Mellor addressed two traditions: a celebrated but delimited culture of poetess, and a contrasting tradition of the female poet in which The Emigrants is representative: explicitly political, self consciously and insistently in the public sphere, and pressing issues not limited to women.

Smith writes across gender, calling on male voices, phrases, and tropes from Virgil, Shakespeare, Milton, Pope, Thompson, Collins, and Gray. This allusiveness is sometimes regarded as the effect of a woman’s internalization and imitation of canonical male voices. The Emigrants is a canny intertextual performance, and its deepest polemics are about tradition itself, literary and political. Mellor remarks, The Emigrants joins an evolving "female" poetry of condemning war as "patriarchal militarism.“ In the 1790s the gender binary was volatile. In a decade when traditions of "British Liberty" were invoked to support the French Revolution, then to oppose the Terror, then to go to war against Napoleon; and when class critiques (the drafting of the poor to fight and die for the interests of the rich) infused many polemics, pacifism and militarism were not predictably or securely gendered discourses. Entering this welter of opinion and writing, Smith recruits male poets to work through conflicts of sympathy and political judgment in the spectacle of the emigrants, then to hope, in the poem's last line, for a renovated earth in an ungendered "reign of Reason, Liberty, and Peace“.

Tho Not on Politics, on a Very Popular and Interesting Subject It wasn't just the politically complex event of the French emigrants that challenged Smith. It was also, and more fundamentally, her signed entry into public debate. Before The Emigrants, in 1791, she was writing her first political novel, Desmond, which, while not interfering in state affairs, did comment on them. It is situated in England and France between June 1790 and early February 1792. In 1790 Helen Maria Williams issued the first of her Letters from France and Wollstonecraft led the charge against Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France in her Vindication of the Rights of Men. Smith used her preface to Desmond to mollify "Readers . to whom the political remarks in these volumes may be displeasing." Ascribing all views to her "imaginary characters," she says her role has been merely to present "the arguments I have heard on both sides; and if those in favor of one party have evidently the advantage, it is not owing to my partial representation, but to the predominant power of truth and reason, which can neither be altered nor conceal’.

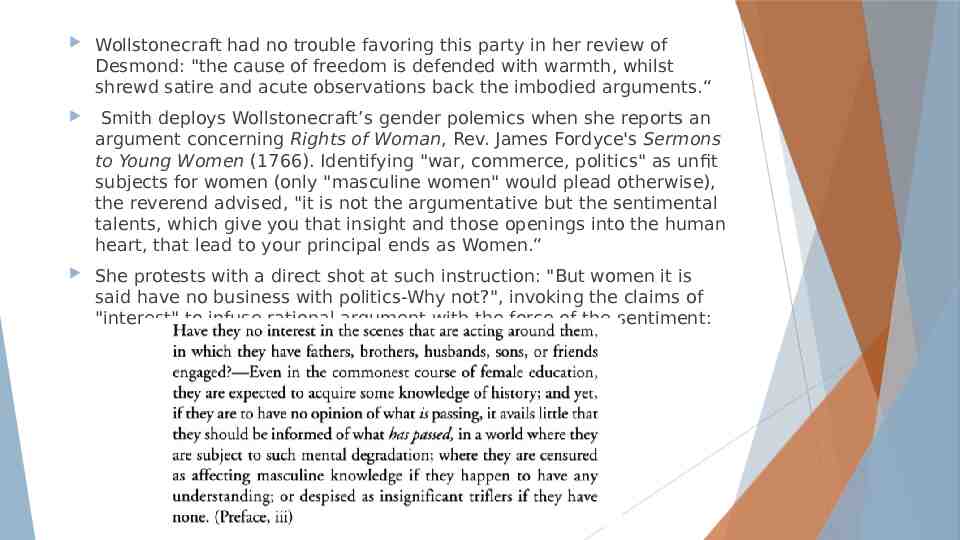

Wollstonecraft had no trouble favoring this party in her review of Desmond: "the cause of freedom is defended with warmth, whilst shrewd satire and acute observations back the imbodied arguments.“ Smith deploys Wollstonecraft’s gender polemics when she reports an argument concerning Rights of Woman, Rev. James Fordyce's Sermons to Young Women (1766). Identifying "war, commerce, politics" as unfit subjects for women (only "masculine women" would plead otherwise), the reverend advised, "it is not the argumentative but the sentimental talents, which give you that insight and those openings into the human heart, that lead to your principal ends as Women.“ She protests with a direct shot at such instruction: "But women it is said have no business with politics-Why not?", invoking the claims of "interest" to infuse rational argument with the force of the sentiment:

In 1792 it was still possible (in the liberal press at least) to escape censure for republican views. But political opinion, especially republican, was risky for a woman writer. In1792 she wrote to bookseller J. Dodsley for advice about The Emigrants, aware that he would have no interest in publishing it. “Tho Not on political, on a very popular and interesting subject” Smith was aware that French emigrants were no simple task: their plight was political and burdened by a long history of contention with Catholic France. In a republican view, they were the backwash of the ancien regime, complicit with a selfish, luxurious aristocracy that still enjoyed connections and property in England. While more than half of the nearly one hundred thousand emigrants to England were Third Estate, the more pathetic narrative was the fall of the clergy and the nobility. Smith laments that English champions of the "name of Liberty," who welcomed the Revolution as "the demolition of regal despotism in France," have been "stigmatized as promoters of Anarchy, and enemies to the prosperity of their country" In the political conception of The Emigrants, however, it is the sires-in the figure of a transhistorical, global, patriarchal war machine-who ultimately stand to account. And it is not the emigrant clergy but the mothers left in France who are its most radical victims.

Classing The Emigrants Smith gives the genre a pan-national, nearly mythic appeal-and writes herself into it. The Emigrants does not open with its eponyms but with Smith herself as fellow-victim, in her case, of "proud oppression" in a country "where the vain boast / Of equal Law is mockery". “It seems to me wrong for the Nation entirely to exile and abandon these Unhappy Men," she wrote early in November 1792 to Joel Barlow, a defender of the Revolution and honorary citizen in the National Convention. The exiles were abject texts of "the impression of the injustice and ferocity of the French republic.“ But as The Emigrants proceeds, the unhappy martyrs show another impression, "the prejudice they learn'd / From Bigotry (the Tut'ress of the blind)“. In this line, "yet unhappy Men, / Whate'er your errors, I lament your fate", Smith may seem to recover sympathy, reflecting on both religious ideology and its social consequences.

She comments bitterly on the pride in both Britain and France of "Men, who derive their boasted ancestry / From the fierce leaders of religious their "splendid trophies / Of Heraldry," she sees only "Gorgons and Hydras, and Chimeras dire” –Milton phrase- This direct quotation of Milton sets the stage for a trope on the most famous (in Romantic-era imagination) epic simile in Paradise Lost, the one limning Satan's enchantment in Eden. Smiths interprets Milton's simile for her own political ends, evoking both the Satanic moment and, more generally, Milton's English Protestant-republican antipathy to Continental Catholic-monarchal decadence. Her trope is energized not by unpatriotic French innovation but by English republican tradition.

Gendering War "the Widow's anguish and the Orphan's tears“, Presenting the widow and orphan's peril-fatal vulnerability- Smith brings the male world of warfare into the female world of home. She was one of the first poets in the 1970s to do this, and it was not easy to be against the war with France, even in terms of female values. As Smith knew, official policy was hardening not only against France but also against agitation at home, especially over the wrongs done to woman and to the poor. Smith is quoting the famous prologue of Henry V (about war with France): She evokes the glory of war (the voice of "O for a Muse of fire“) but laments a "suffering world, / Torn by the fearful conflict“, which she now genders, increasingly, as the work of "Man," with Freedom and Liberty, allegorical females, his victims.

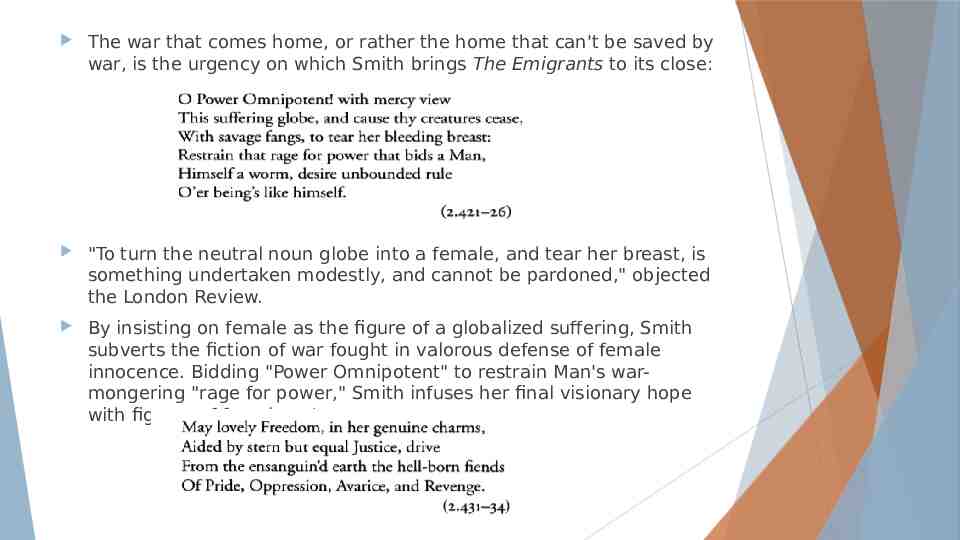

The war that comes home, or rather the home that can't be saved by war, is the urgency on which Smith brings The Emigrants to its close: "To turn the neutral noun globe into a female, and tear her breast, is something undertaken modestly, and cannot be pardoned," objected the London Review. By insisting on female as the figure of a globalized suffering, Smith subverts the fiction of war fought in valorous defense of female innocence. Bidding "Power Omnipotent" to restrain Man's warmongering "rage for power," Smith infuses her final visionary hope with figures of female potency:

Deeper Insights into The Emigrants Charlotte Smith’s “The Emigrants” does not retell heroic deeds by a single protagonist like in Homer’s “The Odyssey”. It is not a traditional epic. In her dedication to William Cowper, Smith writes, “I am perfectly sensible that it [his poem “The Task”] belongs not to a feeble and feminine hand to draw the bow of Ulysses.” Smith genders war as masculine and refuses to write in that language: Smith will not use the militaristic epic form. She will not tell the tale of one man and his adventures, but instead will write of “those interesting objects which happen to excite [her] attention”. In her essay, Susan J. Wolfson suggests Smith “undermines the Burkean ethic of chivalry, of men going to war to protect the women of hearth and home” (Wolfson, 534). In her gendering of war as masculine and Liberty and Freedom as feminine, and finally in her use of the mother, she demonstrate a reading that conflates revolutionary politics and gender politics. The Emigrants an antiwar poem that moves beyond the troubles of the emigrants from Revolutionary France, and thus evoking the “war of the sexes.”

She writes sentimentally throughout The Emigrants, but not without Reason. She compares her own suffering with that of the emigrants. (egotistical) She brings up her own situation by framing it in a way to say, “I understand how you feel, for I have suffered.” Smith writes, “How often, when my weary soul recoils/from proud oppression, and from legal crimes.” “Legal crimes” refers to her husband’s debts and the fact that she had to live in debtor’s prison with him. She alludes to her personal life in a way that goes beyond the personal and into the realm of the political. She writes to the emigrants, “I lament your fate,” or “I mourn your sorrows, for I too have known/Involuntary exile.”

As the emigrants sail in to England’s shore, Smith brings up the mother who “lost in melancholy thought,” mourns for her native land. Smith showed her empathy as both an emigrant and a mother. Smith genders peace as female and suggests that solitude is the only escape from men’s society. She writes, “How often do I half abjure society For I have thought that I should then behold/the beauteous works of God unspoiled by man Peace, who delights in solitary shade,/No more will spread for me her downy wings.” Smith must withdraw from England’s patriarchal society. She wants to escape her husband and look upon the God’s world, which in solitude is “unspoiled by man.” Smith genders Liberty as feminine.

In Book two, Smith alludes to the particular situation of the emigrants. She explains that the “lorn” (lost, perished, doomed to destruction) exiles are “amid the storms/Of wild disastrous anarchy” where “Desolation” (counterrevolutionary forces) riot. Smith uses the storm metaphor to describe France’s state of chaos—that Liberty and Freedom’s name had been “usurped and misapplied,” beginning the violence of the Reign of Terror. Smith claims that the violence of counterrevolution was due to those forces who “resisted” liberty (“the thousands that have bled/resisting her) and that those who sacrificed their lives for liberty are now gone and that most “revert awhile/to the black scroll that tells of regal crimes/committed to destroy her.” Here, “regal crimes” is reminiscent of the phrase “legal crimes” from Book One. This passage can thus be read as a conflation of revolutionary politics, gender politics, and the personal.

Smith sympathizes with Marie Antoinette (“I mourn thy sorrows, hapless Queen”)—but her evocation of motherhood unites all women and suggests that the counterrevolutionary forces are destroying the next generation. Smith writes of Marie Antoinette as a “wretched mother, petrified with grief” for the loss of her son, who Smith characterizes as the “most unfortunate imperial boy.” Smith asserts that what happened to her is inhumane and unjust. Smith aligns herself with Marie Antoinette because of her position as a woman and mother who is consumed by counterrevolutionary violence. Smith writes of her own experience, that she wants, “to save [her] children from the o’erwhelming wrongs/that have for ten years been heaped on me.” This personal allusion fits within the motherhood paradigm she creates in the figure of Marie Antoinette. Marie Antoinette was the last Queen of France before the French

Smith tells the tale of a woman on the mountaintop who dies in the brutality of war. The woman is a mother who is “true to maternal tenderness;” she tries to save her infant from the “storm” (recurrent metaphor.) Through her representation of mothers, Smith demonstrates the destructive masculine ethos of war. The mothers here are not portrayed as being protected by chivalrous men; they are not at the hearth or the home, instead they are being destroyed. She returns to the masculine/feminine binary, suggesting that men create war with other men, thereby “depopulating” England, which significantly, is gendered female. Men thus are depicted as monsters and also as the agents of devastation. A “bleeding world” as gendered feminine evokes an image of a mother’s miscarriage.

Smith prays that Freedom with the aid of Justice might be able to rid earth of the “hell-born fiends” (the arch-enemy of mankind, or the devil). She transcends gender with the last line: “Reign of Reason, Liberty and Peace!” suggesting an ideal resolution where the war of the sexes has ended. Betsy Bolton observes in her essay, “Becoming the Evil We Deplore: Charlotte Smith’s Cautionary Nationalism,” indicates “when she [Smith] observes injuries in others, she promptly draws attention to a parallel injury of her own.” Smith shows intense compassion not only for the emigrants, but also for women.

References Finkelstein, Julia. Close-Reading Romanticism “The Emigrants". https://courses.swarthmore.edu/spring2013/romanticism/wp-content/ uploads/sites/4/2013/02/The-Emigrants Close-Reading.pdf . Wolfson, Susan J. “Charlotte Smiths ‘Emigrants’: Forging Connections at the Borders of a Female Tradition.” Huntington Library Quarterly, vol. 63, no. 4, 2000, pp. 509–546., doi:10.2307/3817615.