Ethical and Legal Issues in Supervision: Essentials for Supervisees

43 Slides853.50 KB

Ethical and Legal Issues in Supervision: Essentials for Supervisees and Supervisors JEFFREY E. BARNETT, PSY.D., ABPP LOYOLA UNIVERSITY MARYLAND

What is Supervision? An intervention provided by a more senior member of a profession to a more junior member or members of that same profession. This relationship is evaluative; extends over time; and has the simultaneous purposes of enhancing the professional functioning of the more junior person(s), monitoring the quality of professional services offered to the clients that she/he, or they see, and serving as a gatekeeper for those who are to enter the particular profession (Bernard & Goodyear, 2004, p. 8).

Understanding Supervision Romans, Boswell, Carlozzi, and Ferguson (1995) have reported that clinical supervision “is a central component in the training of graduate students in clinical, counseling, and school psychology” (p. 407). Clinical supervision is the mental health professions’ “signature pedagogy” (Goodyear, 2007, p. 273).

Key Ethics Issues in Supervision Informed Consent Competence Protection of the Public Accurate Representation to the Public Confidentiality Documentation and Record Keeping Boundary Issues and Multiple Relationships Diversity Evaluation and Feedback Gatekeeper Functions Legal Liability and Responsibility

Supervisee as Consumer You are a consumer of a professional service You have the right to have your training needs appropriately met You have the right to have supervision change as your training needs evolve You have the right to timely and helpful feedback, and honest and objective evaluations, with ongoing chances for remediation when needed You have the right to be respected, to have your contributions valued, to be your supervisor’s sole focus during supervision sessions, and to a safe supervision environment

Supervisee Competence Your training needs and goals should be formally assessed at the outset of the supervisory relationship. Transcript and c.v. review, letters of reference, informal discussion, and formal assessment of knowledge and skills. This should be reassessed over the course of supervision. You should not receive ‘generic’ supervision. Supervision focus and activities should be based on your specific training needs. You should receive ongoing informal feedback in addition to periodic formal evaluations.

Supervisor Competence Supervisor must have two kinds of competence: Competence in providing supervision, and Competence in the areas to be supervised. Supervision should be delegated to an appropriately trained colleague if your training needs exceed the supervisor’s areas of competence in certain areas of practice. Supervisor should be willing to openly discuss her or his training, experience, and expertise with you.

What is Competence? Knowledge Skills Attitudes and Values And the Ability to Implement them Effectively, to include professional judgment The habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community being served based on habits of mind, including attentiveness, critical curiosity, self-awareness, and presence (Epstein & Hundert, 2002, p. 227).

Informed Consent Informed Consent to Supervision Informed Consent between you and your clients Understanding Informed Consent Requirements for Supervision to be Valid Issues to Include in Informed Consent Agreements The Supervision Contract

Understanding Informed Consent The process of sharing information with patients that is essential to their ability to make rational choices among multiple options (Beahrs & Gutheil, 2001) To protect the welfare of clients by offering them the opportunity to make free and informed choices (Corrigan, 2003). Provides the information needed for individuals to make an informed decision about whether or not to participate in a professional relationship. It serves as a means of sharing decision-making power in the professional relationship (Meisel et al., 1977). It promotes autonomy and self-determination, helps minimize the risk of exploitation and harm, fosters rational decision making, and enhances the working alliance (Snyder & Barnett, 2006).

Requirements of Valid Informed Consent It is given voluntarily The individual is competent to consent (legally as well as cognitively/emotionally) We actively ensure the individual’s understanding of what s/he is agreeing to It is documented An ongoing process, not a singular event! Provided verbally and in writing

Informed Consent and Supervisee Rights From the outset of the professional relationship: You have the right to know what is expected of you in supervision and with regard to your clients You have the right to know what you can reasonably expect from your supervisor You have the right to know the range of issues and topics to be addressed in supervision You have the right to know the process for resolving disagreements or disputes and who to contact if difficulties in supervision are experienced

Elements of Informed Consent to Supervision The number and types of clients to be supervised The number of hours of supervision to be provided When and where the sessions will occur The frequency and length of supervision sessions Appropriate reasons for cancelling supervision sessions and the mechanism for doing so Fees and financial arrangements Charges for missed or cancelled sessions The method of supervision, preparation required or expected Limits of decision making by supervisee and responsibility of supervisor for delegating tasks

Elements of Informed Consent (cont.) Expectations for any special requirements such as audio or video taping A detailed timetable for informal and formal written evaluations, evaluation criteria, and standards to be met A clear statement of the limits of confidentiality in the supervisory relationship Documentation requirements Use of outside consultation Emergency contact information Potential reasons and mechanism for terminating the supervisory relationship Procedures for resolving disagreements (Barnett, 1991)

Contracting for Supervision Ethics codes for psychologists require that informed consent be obtained from supervisees as well as other recipients of psychological services. This can be accomplished with a supervision contract. The following are examples of the types of information that should be included. Limits of confidentiality in supervision must be described, and each exception listed. This list should include those exceptions affecting psychotherapy relationships, (i.e., confidentiality will be breached if there is a court order; abuse or neglect of a child or vulnerable adult; potential suicide, homicide or threat of physical harm. Additionally, supervisees must be made aware of any requirements to report unethical behavior that may apply to them. These requirements will depend on which licensing board or boards govern their professional behavior.

Contracting for Supervision (cont.) Confidentiality policies must be established regarding information about both clients and supervisees. For example, the supervisor and supervisee will need to determine whether identifying information about clients will be used in the supervision. If so, clients must be informed that such information will be discussed in supervision, and must consent to participation in therapy with this understanding. If not, supervisees must be advised of their responsibility to protect the identities of clients they discuss. The policy should also include a statement indicating what information obtained in the context of supervision the supervisor will keep confidential. If information will be shared with other staff members at the agency, with college faculty (if the supervisee is a student), or others, supervisees must be so informed at the outset.

Contracting for Supervision (cont.) Supervisory contracts should also include an agreement that: the supervisee will keep the supervisor informed about all significant aspects of his/her client's treatment including suicidality, conflicts between the supervisee and a client, and accusations of unethical behavior, as well as personal factors that could potentially impair the supervisee's effectiveness; the supervisor has the final say in treatment decisions because he/she is legally responsible for the management of the case. Consultation contracts should include information about the limits of confidentiality, but need not contain a mandate about the types of client issues that must be discussed in the consultation. Additionally, a statement clarifying that responsibility for treatment decisions rests solely with the consultee, and not the consultant, should be included. (Thomas, 2006)

Supervision as a Safety Zone The supervisor must provide ‘a safe holding environmen t’. You must feel safe enough to discuss weaknesses, flaws, insecurities, difficulties, fantasies, countertransference reactions, and the like. You need to be able to experiment, try new things, and ‘to fail’ on an ongoing basis. If you are concerned with evaluation and criticism you will be less likely to share openly and less likely to learn. Expectations for a safe supervision environment should be openly discussed from the outset and on an ongoing basis as is needed. Attempt to speak openly with your supervisor and consult with a trusted advisor when needed.

Paranoia vs. Trust Supervision from a developmental perspective based on initial assessment of supervisee training needs and ongoing assessments of professional growth and competence. Supervisor is legally responsible for all professional services provided by the supervisee. Liability Issues: Direct and Vicarious Decisions on the type and intensity of supervision should be thoughtfully made based on the supervisee’s demonstrated competence and training needs.

Supervision Across the Developmental Range Supervisee observes supervisor provide treatment followed by analysis and discussion. Supervisor and supervisee provide treatment together followed by analysis and discussion. Supervisee provides treatment while observed by supervisor – bug in the ear, call-in, etc. Supervisee provides treatment that is videotaped. Videotape and documentation are reviewed by supervisor prior to supervision session. Supervisee provides treatment that is audiotaped. Audiotape and documentation are reviewed by supervisor prior to supervision session.

Supervision Approaches (cont.) Supervisee provides treatment, documents it, and supervisor reviews the documentation prior to the supervision session. (Still may have one case video/audio taped for more intensive supervision) Vary approach based on specific client types: presenting problems, techniques used, complexity of case, etc.

Accurate Representation to the Public Never imply practicing Independently. See relevant ethics code standards. See relevant laws E.g., in Maryland “Psychology Associate.” In written communications may only represent oneself as a Psychology practicing under the supervision of (name of psychologist), Maryland licensed psychologist number (license number). Or, “I am a graduate student in psychology practicing under the supervision of .” Never imply practicing independently. Always ensure that clients know that you are being supervised, by whom, and how to contact her/him if needed.

Confidentiality and Its Limits Ensure a clear understanding of the limits of confidentiality and including this in the informed consent agreement/contract: Between supervisee and client (mandatory exceptions to confidentiality relevant to all clients as well as how supervision impacts confidentiality such as review of documentation and audio/video tapes, observation of sessions, etc. Know the limits to confidentiality in your jurisdiction. Between supervisor and supervisee (feedback to training program or others, etc.)

Documentation See APA Ethics Code (http://www.apa.org/ethics/) See APA Record Keeping Guidelines (http://www.apapracticecentral.org/ce/guidelines/index.aspx) Documentation of professional services provided by the supervisee to clients Documentation of supervision sessions by both supervisor and supervisee Accountability, record of what transpired, agreements and obligations, follow-up, evaluations of supervisee, etc.

Documentation of Supervision All issues discussed Recommendations made Actions taken Assignments given Review of follow up of previous assignments Additional training/remediation recommended Outcomes and results achieved (Barnett, 2000) Store and retain documentation of supervision sessions as you would clinical records

Legal and Ethical Issues The Regulatory Environment: Knowledge of your profession’s ethics code Knowledge of relevant laws, regulations, and practice guidelines Knowledge of site-specific policies, rules, and regulations

Relevant Standards of the APA Ethics Code 2.01 2.03 2.05 2.06 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.08 3.10 4.01 4.02 4.03 Boundaries of Competence Maintaining Competence Delegation of Work to Others Personal Problems and Conflicts Avoiding Harm Multiple Relationships Conflict of Interest Exploitative Relationships Informed Consent Maintaining Confidentiality Discussing the Limits of Confidentiality Recording

APA Ethics Code (cont.) 5.01 Avoidance of False or Deceptive Statements 6.01 Documentation of Professional and Scientific Work and Maintenance of Records 6.04 Fees and Financial Arrangements 6.06 Accuracy in Reports to Payors and Funding Sources 7.06 Assessing Student and Supervisee Performance 7.07 Sexual Relationships With Students and Supervisees

Diversity Issues in Supervision Multicultural Competence by supervisor and supervisee Integrating attention to diversity issues into all treatment and supervision sessions – intentionally making this a focus of supervision, in the supervisory relationship, in the treatment relationship, and in the client’s treatment (e.g., diagnosis, conceptualizing the client’s difficulties, etc.) Seeing multicultural competence as essential to being competent Taking a broad view of diversity (See APA Ethics Code Principle E). See APA Multicultural Guidelines

Principle E: Respect for People's Rights and Dignity Psychologists respect the dignity and worth of all people, and the rights of individuals to privacy, confidentiality, and selfdetermination. Psychologists are aware that special safeguards may be necessary to protect the rights and welfare of persons or communities whose vulnerabilities impair autonomous decision making. Psychologists are aware of and respect cultural, individual, and role differences, including those based on age, gender, gender identity, race, ethnicity, culture, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, disability, language, and socioeconomic status and consider these factors when working with members of such groups. Psychologists try to eliminate the effect on their work of biases based on those factors, and they do not knowingly participate in or condone activities of others based upon such prejudices.

Boundary Issues and Multiple Relationships Supervisor as Role Model Standards in the APA Ethics Code Strict adherence to Boundaries Boundary Crossing Boundary Violations Supervision vs. Psychotherapy for the Supervisee Multiple Roles vs. Multiple Relationships Compartmentalizing Roles and Responsibilities

Consultation When unsure of any of these or related issues, consult with an experienced and trusted colleague. Regarding legal issues, consult with an attorney. If uncomfortable with how the supervision process or relationship are proceeding attempt to discuss this issues openly with your supervisor. If that is unsuccessful, or if it is not possible, consult with a professor or advisor. Do n’t just let things continue while hoping that they will get better.

Evaluation and Feedback Program Requirements Informal Verbal Feedback on an Ongoing Basis Periodic Written Feedback as Specified in the Informed Consent Agreement Evaluation criteria and rating form shared from the outset Knowing with whom the evaluation results are shared Supervisor as Gate Keeper to the Profession

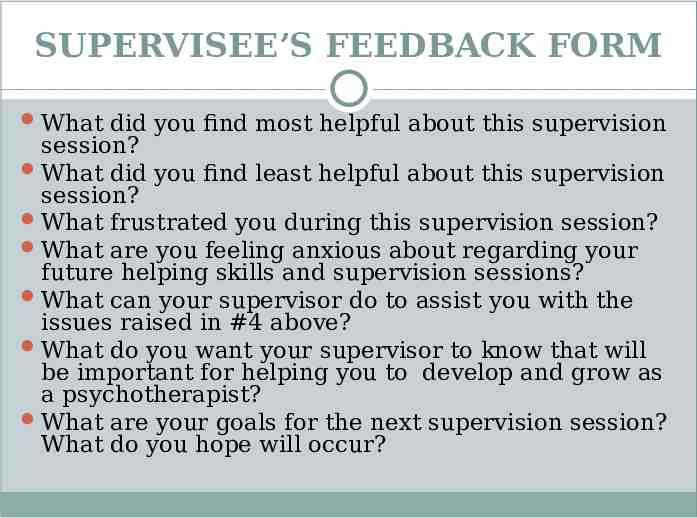

SUPERVISEE’S FEEDBACK FORM What did you find most helpful about this supervision session? What did you find least helpful about this supervision session? What frustrated you during this supervision session? What are you feeling anxious about regarding your future helping skills and supervision sessions? What can your supervisor do to assist you with the issues raised in #4 above? What do you want your supervisor to know that will be important for helping you to develop and grow as a psychotherapist? What are your goals for the next supervision session? What do you hope will occur?

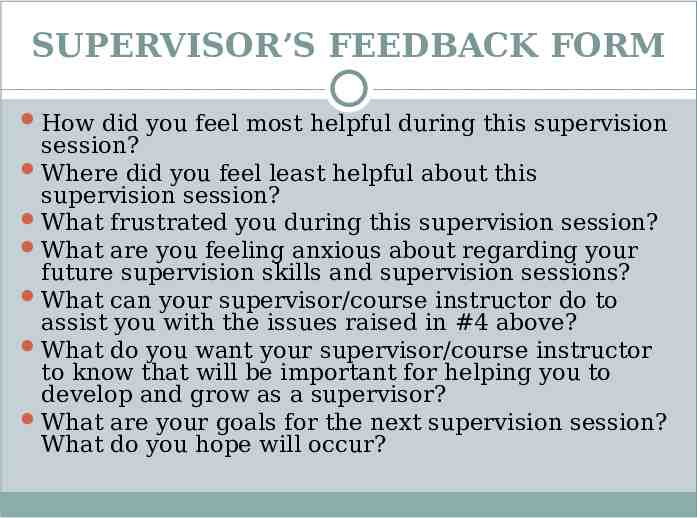

SUPERVISOR’S FEEDBACK FORM How did you feel most helpful during this supervision session? Where did you feel least helpful about this supervision session? What frustrated you during this supervision session? What are you feeling anxious about regarding your future supervision skills and supervision sessions? What can your supervisor/course instructor do to assist you with the issues raised in #4 above? What do you want your supervisor/course instructor to know that will be important for helping you to develop and grow as a supervisor? What are your goals for the next supervision session? What do you hope will occur?

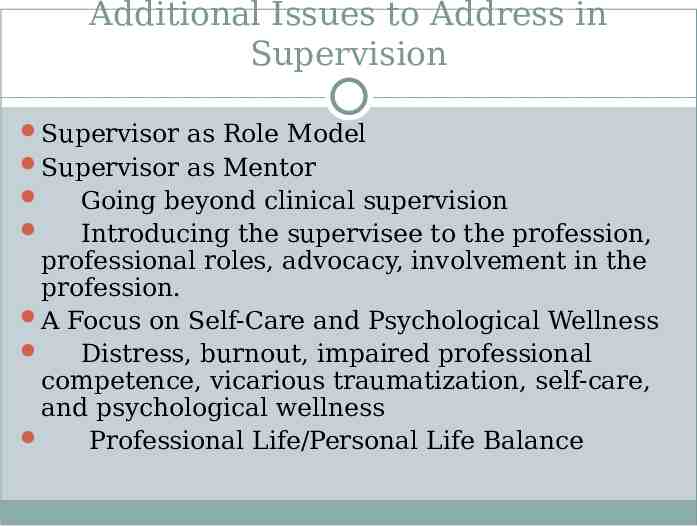

Additional Issues to Address in Supervision Supervisor as Role Model Supervisor as Mentor Going beyond clinical supervision Introducing the supervisee to the profession, professional roles, advocacy, involvement in the profession. A Focus on Self-Care and Psychological Wellness Distress, burnout, impaired professional competence, vicarious traumatization, self-care, and psychological wellness Professional Life/Personal Life Balance

Key Issues to Consider What Supervisees (and Supervisors!) Don’t Talk About and Why! (See Pope, Sonne, & Greene’s What Therapists Don’t Talk About and Why. 2006. APA Books.

Top ten factors contributing to “Best” supervisor ratings (In descending order): Clinical knowledge and expertise Flexibility and openness to new ideas and approaches to cases Warm and supportive Provides useful feedback and constructive criticism Dedicated to students’ training Possesses good clinical insight Empathic Looks at countertransference Adheres to ethical practices Challenging (Martino, 2001)

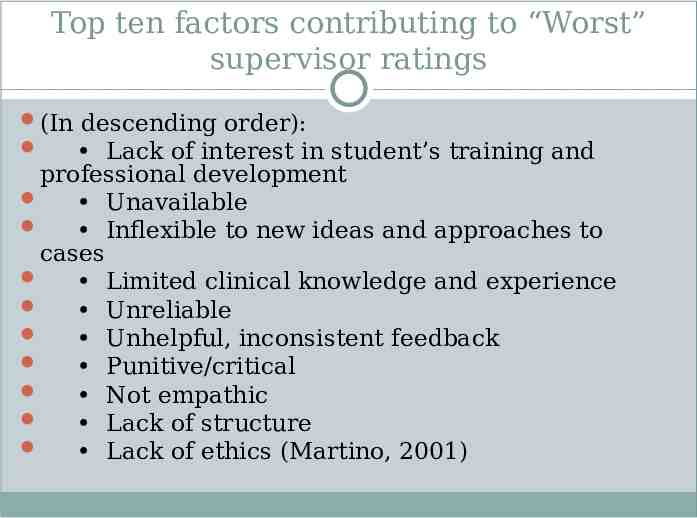

Top ten factors contributing to “Worst” supervisor ratings (In descending order): Lack of interest in student’s training and professional development Unavailable Inflexible to new ideas and approaches to cases Limited clinical knowledge and experience Unreliable Unhelpful, inconsistent feedback Punitive/critical Not empathic Lack of structure Lack of ethics (Martino, 2001)

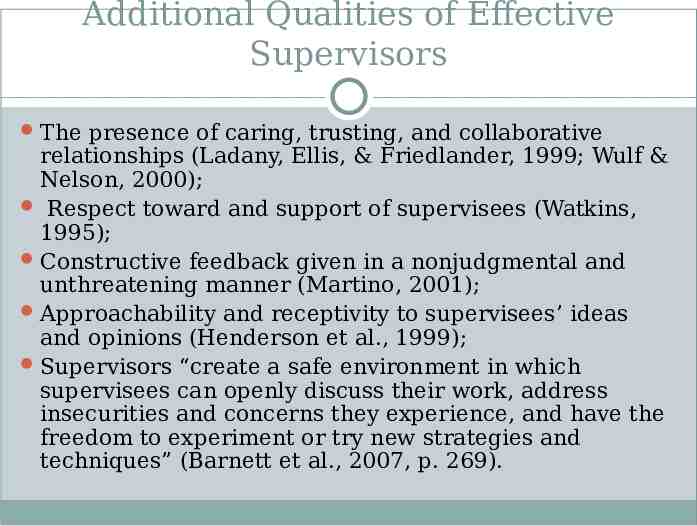

Additional Qualities of Effective Supervisors The presence of caring, trusting, and collaborative relationships (Ladany, Ellis, & Friedlander, 1999; Wulf & Nelson, 2000); Respect toward and support of supervisees (Watkins, 1995); Constructive feedback given in a nonjudgmental and unthreatening manner (Martino, 2001); Approachability and receptivity to supervisees’ ideas and opinions (Henderson et al., 1999); Supervisors “create a safe environment in which supervisees can openly discuss their work, address insecurities and concerns they experience, and have the freedom to experiment or try new strategies and techniques” (Barnett et al., 2007, p. 269).

Resources Barnett, J. E. (1991). The supervision of psychological services: Legal and ethical guidelines. The Maryland Psychologist, 37(2), 11-12. Barnett, J.E. (2000). The supervisee’s checklist: Attending to ethical, legal, and clinical issues. The Maryland Psychologist, 46 (1), 18-19. Barnett, J. E., Doll, B., Younggren, J. N., & Rubin, N. J. (2007). Clinical competence for practicing psychologists: Clearly a work in progress. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38, 510-517. Barnett, J. E., Erickson Cornish, J. A., Kitchener, K. S., & Goodyear, R. K. P. (2008, August). Supervisor and supervisee ethical expectations – What goes on behind closed doors? Symposium presented at the annual convention of the American Psychological Association, Boston, Massachusetts. Barnett, J. E., Pitta, P., Lowry, J., Campbell, L., & Martino, C. (2001, August). In J.E. Barnett (chair) Secrets of successful supervision – Clinical and ethical issues. Symposium presented at the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco, California. Beahrs, J. O., Gutheil, T. G. (2001). Informed consent in psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 4- 10. Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (2004). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (3rd ed.). Boston: Pearson Education.

Resources (cont.) Corrigan, O. (2003). Empty ethics: The problem with informed consent. Sociology of Health & Illness, 23, 768-792. Croarkin, D. O., Berg, J., & Spira, J. (2003). Informed consent for psychotherapy: A look at therapists understanding, opinions and practices. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 57 (3), 384-400. Epstein, R. M., & Hundert, E. M. (2002). Defining and assessing professional competence. Journal of the American Medical Association, 287, 226–235. Falender, C. A. & Shafranske, E. P. (2004). Clinical Supervision: A CompetencyBased Approach. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Henderson, C. E., Cawyer, C. S., & Watkins, C. E. (1999). A comparison of student and supervisor perceptions of effective practicum supervision. Clinical Supervisor, 18, 47-74. Kaslow, N. (2004). Competencies in professional psychology. American Psychologist, 59(8), 774-781. Ladany, N., Ellis, M.V., & Friedlander, M.L. (1999). The supervisory working alliance, trainee self-efficacy, and satisfaction with supervision. Journal of Counseling & Development, 77, 447-455.

Resources (cont.) Meisel, A., Roth, L. H. & Lidz, C. W. (1977). Toward a model of the legal doctrine of informed consent. American Journal of Psychiatry, 134, 285-289. Miller, D. J., Thelen, M. H. (1986). Knowledge and beliefs about confidentiality in psychotherapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 17, 15-19. Rodolfa, E., Bent, R., Eisman, E., Nelson, P., Rehm, L., & Ritchie, P. (2005). A cube model for competency development: Implications for psychology educators and regulators. Professional psychology: Research and practice, 36(4), 347-254. Romans, J. S. C., Boswell, D. L., Carlozzi, A. F., & Ferguson, D. B. (1995). Training and supervision practices in clinical, counseling, and school psychology programs. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 26, 407–412 Snyder, T. A., & Barnett, J. E. (2006). Informed consent and the psychotherapy process. Psychotherapy Bulletin, 41, 37-42. Watkins, C. E. (1995). Psychotherapy supervision in the 1990s: Some observations and reflections. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 49, 568-581. Wulf, J., & Nelson, M. L. (2000). Experienced psychologists’ recollections of internship supervision and its contributions to their development. Clinical Supervisor, 19, 123-145.